With all due respect to the man known as Copper King, and the person who Clark County, Nevada is named after, William Andrews Clark, the true, the first, the original “father of Clark County” was Marius Samuel Beal.

This eleven-page article will detail the early development of Las Vegas through the actions of a world traveler, who very late in life, would move to a railroad camp on the edge of the Mojave desert, and what he did to create the county of Clark.

M.S. Beal, soon to be given the title “Judge” out of respect, arrived in the railroad camp of Las Vegas in the fall of 1904.

A photograph of the camera shy Beal would be seen only once in the Las Vegas newspapers.

Las Vegas Age, February 12, 1910, Page One

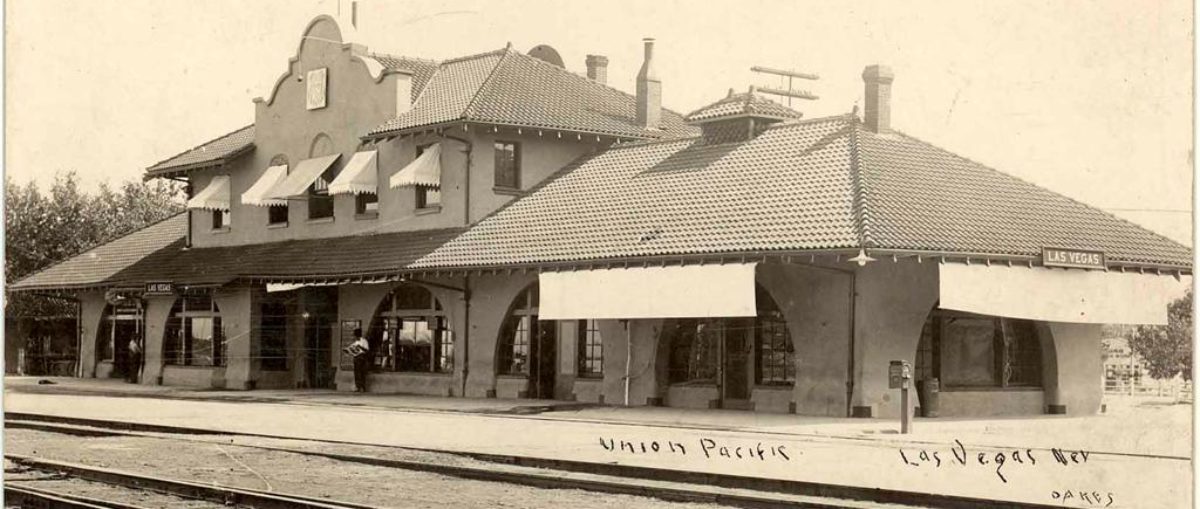

The population and business center of Las Vegas when Beal arrived in 1904, was located where Las Vegas Boulevard and Main Street connect.

Coming in from the north, the railroad tracks were getting close to Las Vegas. By the end of the year you could hop a train from Salt Lake City to Las Vegas. It would be the following year before the rail line would provide passenger service through to Los Angeles.

The famous May 15, 1905 land auction creating the town of Las Vegas was months away.

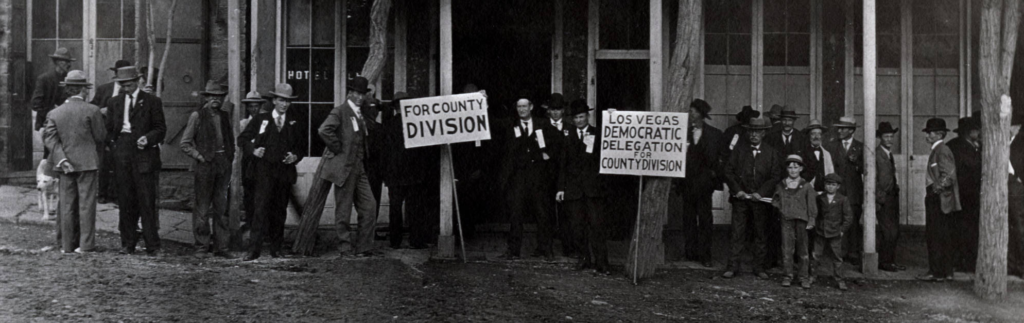

At this point the discussion, not yet to the level of debate, had begun over the need to create a new county out of the southern half of Lincoln County.

The center of that discussion was to the south of Las Vegas in Searchlight. Its residents complained, while they paid taxes, they received little help from the county seat in Pioche, located at the far northern end of the county. “You can’t get there from here” was the common complaint from Searchlight residents. Before the railroad, a trip to the county seat in Pioche from Searchlight was a two week adventure by wagon over rough trails. Even after the railroad it would take you a week.

With Las Vegas on its way to becoming a town with a rail line linking it to the outside world and much of southern Nevada taxes and access to government services became regular topics of discussion. At the top of the list, the problems with doing business at the seat of county government. The county courts, and other essential government offices, as well as the monthly meetings of the county commission were located in the far northern end of the county in Pioche. And then there was the infamous Lincoln County Courthouse that was costing taxpayers several hundred thousand dollars.

Citizens of the area put several proposals on the table. The first came from the leaders of Lincoln County. They were all for leaving things as is. The second came from the folks settling in Las Vegas. They had a couple of ideas. First, simply move the county seat to Las Vegas, the center of Lincoln County. They second option was to cut Lincoln County in half and make Las Vegas the capital of the county. Searchlight residents were all for cutting Lincoln County in half but they wanted their town to be the county seat.

The discussion was quickly becoming a lively debate.

At the time Senator Clark was in Washington, D.C., busy representing Montana and his railroad interests. In fact, until the end, he even opposed the idea of forming a new county worried that he would be taxed by two counties.

Meantime, “Judge Beal” was working away at the grassroots level, writing the legislation that would pave the way for a much more practical, functional and safer jurisdiction for his fellow Las Vegans. And it was Beal who saw to it that this new county would bear Clark’s name.

But like many other important things that Beal accomplished during his five years in Las Vegas, there are no monuments to the progress he prompted.

No water facility is named after him, yet he led the way in the development of water resources in the Las Vegas Valley.

Nothing can be found about Beal at the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce, yet he helped form and led the civic group that would become the chamber.

And there’s no trace, or mention of Beal in the stories of the mountains around the Las Vegas valley, yet he fought successfully to save the forests from the ax.

The only reminders of his influence are tucked away behind the scenes, in dusty records and old newspapers. Otherwise he might as well have been a wandering ghost of good fortune who mysteriously blew into town one day.

The mystery part is true.

There aren’t many clues as to why an accomplished man like Beal ended up in one of the last major boomtowns of the Wild West. But you would have to start with this tragic fact from his past: 13 years before Beal came to Las Vegas, his wife died giving birth to their fifth child.

He and Marie Elizabeth McComas were married on July 21, 1869, in Louisville, Kansas. They settled in as a family on the plains of the American frontier and had four children during the 1870s.

Beal was a lawyer by trade, and he served in the elected position of district court clerk for 10 years. Meantime, he and his two brothers created a title company, then established a bank, followed by a land agency and insurance business.

Beal was a large man, with brawn that was equal to his brain. He was a picture of Old West ruggedness. Like his father, who had led his family from Indiana to Kansas after the Civil War, Beal had an innate sense of adventure. His first big move was to the Oklahoma Territory in the late 1880s, at a time of the great land rush, and he began working with many of the state’s leading politicians. “For several years,” the Las Vegas Age would later report, “he was a resident of Indian Territory among the Indians of the Cherokee Nation.”

In 1890, the Beals packed up and headed to Colorado, where, according to the Age, “he became a part of the life of the great camps of Creed and Cripple Creek in the days of their worldwide fame.” Beal also practiced law for a while in Denver.

In the spring of that year, Mrs. Beal became pregnant. On January 21, 1891, she gave birth to her second daughter. Six days later, at the age of 38, she died.

The newborn was named Marie in honor of her mother, and Beal quickly made arrangements for her to be taken care of by her 20-year-old married sister, Florence, who had stayed behind in Oklahoma. Beal continued to work in Denver through the 1890s, and at the turn of the century he pushed west again, landing in San Francisco.

From the City by the Bay, Beal sailed to Japan, China and the Philippines Islands. He even traveled around the horn of South America and visited Africa. Whether he was simply seeing the world or he was soul-searching, we’ll never know. But in 1904, it is clear that he decided to make one more journey.

While ashore in San Francisco, Beal heard about Senator Clark’s plan to build a railroad from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles.

What may have captured his attention was the turning of Las Vegas from a desert oasis to the construction of a massive health resort.

Why did that have appeal after traveling the world and living in one of its most sophisticated cities? And at age 56—10 years beyond the average life expectancy of an American male in those days—what did he expect to find in a lawless, rough-and-tumble camp town on the southern edge of the great basin of Nevada?

Beal may have been used to the frontier life, but it still must have taken some adjusting to Southern Nevada in 1904.

When he rolled into Las Vegas aboard a horse-drawn wagon (the train would only take passengers as far as Moapa at this point), he would find a tent city.

While there was in fact a butcher and a baker, the temporary business district revolved around the constant opening of tent saloons, serving different occupations and nationalities of the railroad workers.

In addition to the saloons, there was a butcher, a baker, not sure about the candlestick maker, but there was a barber (inside one of the saloons).

The community was stretched out around the valley’s two main ranches, the original Stewart Ranch, north to the Kiel Ranch, both owned by the railroad.

The largest concentration of activity was at the bottom of the hill, about a mile north of Fremont Street.

The place was infested with “a large number of rounders and garoters,” according to Southern Nevada’s largest newspaper, the Lincoln County Record.

And Sheriff Jake Johnson, after returning from the 100-mile trip down south, gave an interview to his hometown paper, the Delamar Lode, which led to an article that declared Las Vegas to be “the toughest town in Lincoln County.”

As Beal was settling in he quickly became friends with the Bracken brothers, Joseph and his younger brother Walter. He briefly worked for Walter as assistant postmaster before establishing his law practice.

Dr. Joseph Bracken, a medical doctor, after leading a railroad construction crew through Meadows Valley he was sent to Las Vegas in 1903 to manage the Kiel and Stewart ranches his uncle, Senator Clark had purchased for the railroad.

Dr. Bracken in turn a year later hired his younger brother Walter to help him with the ranch.

Ownership of the railroad by this point was cut in two. The Union Pacific, led by E. H. Harriman owned fifty percent of the line, while Senator Clark controlled the other half.

Construction of the actual railroad was led by the senators brother J. Ross Clark, who in turn was controlled by a committee of both the Harriman forces and those representing the Clark Brothers.

The committee, in 1904, ordered Dr. Bracken to fire Walter in an effort to save money. For a short time the younger Bracken was off the payroll, but he was still the local postmaster, and there was still a need for help to protect the railroads property in a rough and tumble construction camp environment.

Dr. Joseph Bracken wrote to the railroad bosses a “gang of toughs” was “committing so many deprecation that I think it absolutely necessary to have a paid watchman.” The railroad owners said, no.

Meantime, local valley citizens petitioned the Lincoln County Commission for organized law including a Las Vegas justice of the peace and a constable.

They received only the former despite the fact that the Lincoln County Record had predicted Las Vegas—not Pioche or Caliente—would be the city of the future in Southern Nevada. And that future began when the two ends of the railroad were connected on January 30, 1005, about 34 miles south of town. Soon work trains began to move up and down on the line on a regular basis, and on May 1, passenger service started. Las Vegas was indeed a happening place.

By January of 1905 Las Vegas had moved again.

This time the railroad did not own the land. This time the town popped up west of the railroad tracks to an area between Bonanza Road and Washington.

Most of the saloons quickly moved to the new town site. The other business would soon follow and new ones opened up, including a bottling plant for soft drinks.

The new location, titled by its owner J.T. McWilliams, as the “Original” Las Vegas Townsite, would bustle with activity, but only for a few months.

However, the tent town called “Las Vegas” had one more move before it would settle down.

The railroad was keeping the location of where it would officially build the town a secret. The site only became apparent when the “friends” of the railroad were allowed to build tent structures along what is now Main Street.

Beal was one of those who made the move. On February 1, 1905, he opened his law practice in the post office tent, which was relocated to what would become the intersection of Main and Fremont.

By now Beal was being called “Judge,” out of respect for his legal mind and just demeanor. The Age described him as “an old frontier lawyer, and though he has spent some years in San Francisco, his interests and inclinations have always led him back to the border.”

Beal’s inclinations also led to his keeping a ledger. He recorded who owned and who sold land in Las Vegas. He noted the historic “firsts” of the new community, from the arrival of the first passenger train to the first circus. And he observed the daily weather conditions of Las Vegas, recording precipitation, wind speed and direction, and the number of “pleasant” days. In 1905, he counted 239.

The temperate hit triple digits on the mid-May day when an estimated 2,000 people gathered for the land auction at the railroad’s town site.

In the wake of what is now considered Las Vegas’ birthday, Beal was soon involved in nearly every enterprise that contributed to the foundation of the community. If there was a need, Beal helped create the organization to fill it—from a home loan association to a road commission.

Beal and his new friend Peter Buol, were named the first Las Vegas Road Commissioners. In a few years Buol would become the city’s first mayor.

In October, 1905 Beal became secretary of the newly formed Vegas Artesian Water Syndicate, and on that occasion he told the Las Vegas Times, “We believe that artesian water may be had in abundance.” He was right, and would later proudly pose for a photograph standing next to the company’s first well.

When local businessmen organized a Board of Trade, Beal was on hand to lend his expertise. He was appointed along with Peter Buol to develop plans to create a more responsive county and municipal government. The seeds of making Las Vegas the county seat took hold at this meeting.

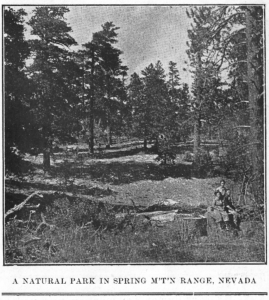

Before the doors on 1905 were closed, Beal raised his hand again and became the community’s first environmentalist. Alerted to the fact that sawmills were being built in the Mount Charleston area, he went on a crusade to protect the forests. One sawmill boasted that it would produce up to 30,000 feet of lumber per day at one site alone. Beal circulated petitions, wrote letters and encouraged his friends at the three local newspapers to write stories about the potential environmental impact.

As a result, in January 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed the nearby mountain range the Charleston National Forest. While the Age ran an editorial commending the “noble work” that Beal has been doing in effort “to have the government encourage the growth of forests in southern Nevada,” the proclamation did not halt those who already had logging permits. The Age predicted that the Charleston Mountains could “become a grand summer resort if the vandals are not permitted to skin it of all the timber.”

Beal again circulated a petition, this time calling for a complete end to commercial tree cutting in that forest. He eventually met with the chief forest inspector for the region, and in their discussions, he expanded his request to protect not only the forest on Mount Charleston but that on the Sheep Mountain ranges as well. On December 12, 1907, President Roosevelt ordered that the 195,840 acres of the Sheep Mountain range be preserved as the Las Vegas National Forest.

Photograph used by Beal photograph to support preservation of mountains north and west of Las Vegas. Spring Mountains, Fall 1909.

An elated Beal did not confine his efforts to conservation in the nearby mountains; he also successfully urged residents and the railroad to plant trees in the valley. For Beal, it was not only a matter of preserving the land for the future, but making the community more livable in the meantime.

From the time the Record predicted in 1905 that Las Vegas would become “the metropolis of Lincoln County,” a movement to move the county seat had begun. It was rejected out of hand by those in power, but it was increasingly clear that something had to be done. The county was the largest in the United States, and Las Vegas residents, even with the train, were still three days of rough travel away from Pioche, the seat of government.

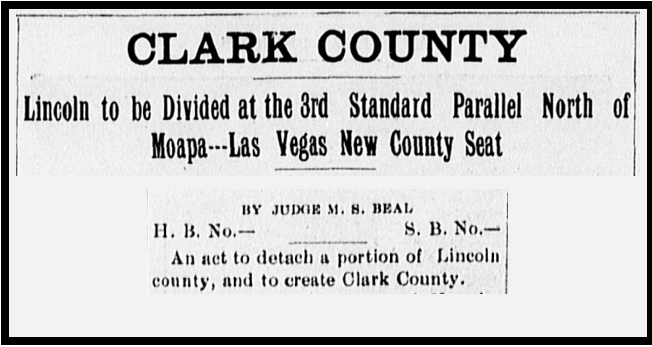

A second solution was to carve the territory in half, creating “Fremont County” (named in honor of the famous explorer). At the dawn of 1908, only two things stood in the way: the “Million Dollar” Lincoln County Courthouse and the railroad.

Judge Beal, of course, put himself at the center of the action. In the spring he wrote to Senator Clark asking for his thoughts on dividing Lincoln County as well as building of a horse-racing track in Las Vegas.

There was little encouragement from the senator on either matter. On the county issue, according to the Age, he responded: “My Dear Mr. Beal … It is a matter that requires some study and therefore I do not desire to commit myself to it at the present time.”

Between the lines was Clark’s concern that, with two counties, his tax payments for tracks and buildings in Southern Nevada would double. Beal realized this, and as a member of the Lincoln County Division Club, he prepared a detailed analysis of the financial impact on the railroad. His work held up under the scrutiny of the railroad accountants, at which point Clark withdrew any opposition to the division.

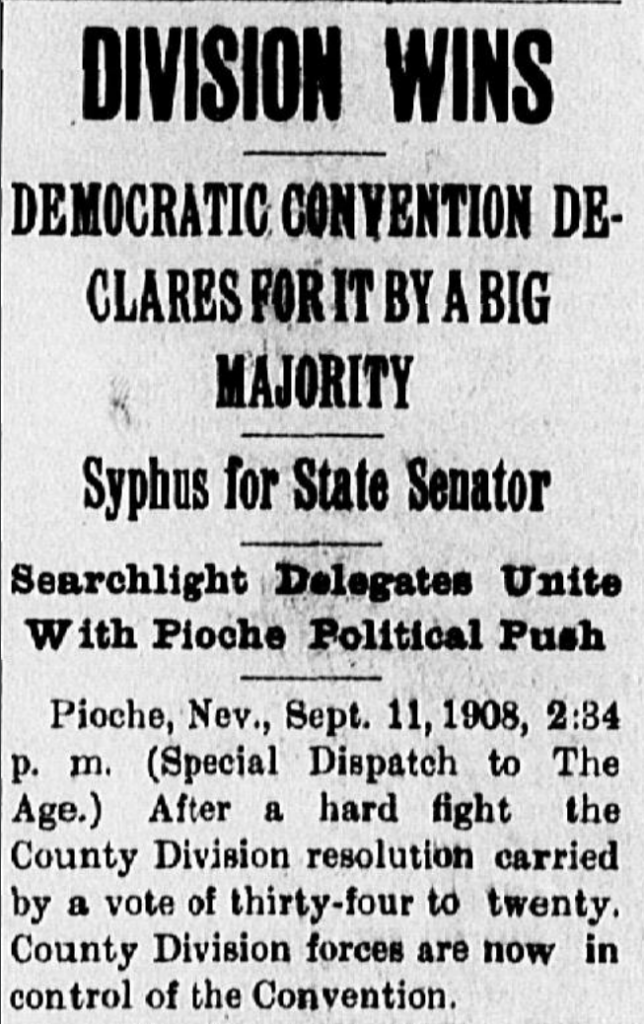

September 10-11, 1908 in Pioche.

Las Vegas Age, September 12, 1909, Page one.

Las Vegas Age, September 12, 1909, Page one.

Beal’s plan to divide the county had two key elements. The first was his overall analysis of the financial impact not just on the railroad but on the county and proposed county.

Clark County Review owner and editor, Charles Corkhill wrote the data Beal had compiled was of “incalculable benefit in justifying the issue and winning the cause.”

Over at the Las Vegas Age, its owner and editor, Charles P. Squires echoed Corkhill’s sentiment, writing that Beal’s “painstaking detail work” over many months “is largely due to the success” of the creating Clark County.”

The proposed division of Lincoln County would keep everything north of Moapa and Bunkerville. Most of the population and the largest section of the railroad would be in the newly created county of Clark. This map was published in the February 6, 1909 issue of the Las Vegas Age.

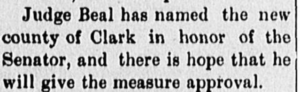

The second part of Beal’s plan was his campaign to change the county’s proposed name from Fremont to Clark.

It was Clark, Beal said who “caused these railroad to be built, and to whose energy and public spirit the improvement here are honestly and gratefully credited by those who are enjoying the benefits of his far-seeing eye.”

Las Vegas Age, June 6, 1908, Page one

With no opposition to the name change from the citizens of the proposed county, or the senator himself, Beal made the change in the proposed legislation.

The final step was to get the approval of the Nevada Legislature. Beal was the one who drafted the bill that was submitted to Carson City, and with little change, it passed both houses. Clark County was signed into law on February 5, 1909, by Governor Denver Dickerson, and became a reality on July 1.

Corkhill concluded of Beal’s effort: “The act creating Clark County was the product of his brain, without price and without cost.”

As he was battling to create Clark County, Beal also set to work creating an organization to boost the Las Vegas valley. He incorporated the non-profit operation under the name “Las Vegas Promotion Society.”

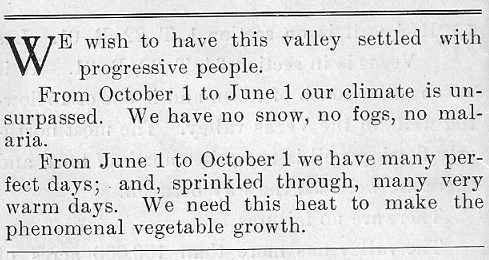

Late in 1909, Beal produced a small 3 ¼ by 6 ¼ ten panel black and white brochure promoting Las Vegas and Clark County. On the front panel, Beal, in an effort to separate it from land scams, said the society “has nothing to sell.”

He simply said the organization’s mission was “to show the outside world the vast possibilities of development in the new County of Clark in a business-like manner.”

W.R. Thomas, who would soon become the county’s first district attorney, was named president Promotion Society; Beal, and his business partner, Buol, were named to the board of directors. On a volunteer basis,

And, to be clear, Buol, who at the time was the U.S. Land Commissioner, who also sold land in the valley would benefit from the mission of the Promotion Society.

Beal had five thousand of the brochures were printed at the Las Vegas Age by his friend Squires.

Thousands were distributed throughout California and by the railroad at its various depots.

In each folder, along with the annual weather forecast for the valley was the statement; “We wish to have this valley settled with progressive people.”

And, as far as the weather, Beal felt compelled to point out that in addition to not having any snow or fog, Las Vegas had “no malaria. From June 1 to October 1 we have many perfect days and, sprinkled though, many very warm days.”

(ahh yes, July in Las Vegas is in fact “sprinkled” with “many very warm days.”)

Sadly the weather would not agree with Beal this time, as a massive storm hit the southern part of Nevada during Christmas New Year’s week.

The storm washed out the rail lines north of Las Vegas cutting the community off from Salt Lake for several months. No trains were able to connect Los Angles to Salt Lake between Christmas week 1909 and the spring of 1910.

The storm hit Las Vegas, dropping 10 inches of snow. Train service was knocked out north and south of town, leaving the community marooned.

It was during this time that Beal had taken ill. He stayed at home in the “cozy little cottage he had fitted up for a home” (on the west side of Third Street across the court house).

After resting for a couple of weeks Beal was able to return to the office he shared with Buol next door to the bank on the corner of First and Fremont.

But, on January 26, Beal became sick again and was “confined to his bed.” Four days later he was dead.

“Judge Beal is dead!” was the top headline in Corkhill’s paper. The Clark County Review reported Beal’s “massive and powerful frame weakened and his vital forces dissolved by a sudden attack of pneumonia contracted from exposure during the recent severe and unusual weather.”

The Las Vegas Age found a photograph of Beal standing with one of the ‘Judge’s’ projects; drilling for water.

Following the funeral, the pallbearers (including Hawkins, Bracken and Corkhill) escorted Beal’s remains up Fremont Street to the railroad depot. Despite the “cold and disagreeable” weather, a large group of friends gathered at the depot to pay their last respects as his body was sent back to Kansas.

The eulogies came in quickly. Corkhill said it was Beal’s “understanding of the law and what it is not good for, his sterling integrity, that made him the confidential adviser of nearly all the substantial business interest of this section.”

Squires wrote, “It may be of interest to the many acquaintances of the deceased to know that, in the lonely life he led in his little home on Third Street, the Holy Bible, in which his name was lovingly inscribed by the hand of his aged mother years ago, was his constant companion and inspiration. And there are few so well versed in the Bible or who gave it such constant and living study as did our friend Judge Marius S. Beal.”

While we will never know what really brought him to Las Vegas, this “lonely life in his little home” might be an indication of the lingering sorrow over the loss of his wife. Corkhill said that Beal “lived to a great extent within himself,” adding “he was naturally reticent and of a retiring disposition.”

What about his sons and daughters?

The 1900 U.S. Census shows nine-year-old Marie living with her sister in Oklahoma City. Years later when asked about Marie, Florence admitted that she had “raised and care for her since birth.” While in Las Vegas, Beal confided to friends that he had not seen his youngest daughter since she was born. “From the day he arrived,” Squires wrote, “Beal never left the Las Vegas Valley until he died.”

And he evidently had only one visitor in five years: His son Carroll stayed here for four months in 1906, serving as assistant postmaster.

Judge Beal could have gone anywhere to make his mark on a community, to start a new life, to find a fresh frontier experience, or simply to try and forget his anguish—to achieve whatever he was seeking to accomplish. But, for reasons we’ll never know, he chose Las Vegas, which was far away from reminders of his past.

“I am sure he would have been recognized in any gathering of men as a distinguished gentleman,” Squires wrote. “At least we, who were thrown with him in this raw, rough unformed country community, knew he was such—well educated, cultured and, above all a friend of men.”

Little has been done to recognize the lasting legacy Beal has provided southern Nevada for the future.

To date, I could not find a street in Clark County Vegas named after him. If the county commissioners are not up to naming a street for ‘Judge’ Beal, how about, at least a mention in the county online “Timeline of Clark County History -People and Events.”

ifhttp://www.clarkcountynv.gov/parks/Documents/centennial/history-timeline.pdf