Yep, that was Will Rogers who call Nevada “freedom’s last stand in America.”

Not sure Will was talking about gambling, or marijuana, but he did know there was something special about Nevada.

Despite the fact the airplane he was flying in flipped on its back when landing in Las Vegas, he liked the “dandy little city.”

And he did one of his last films at Lake Tahoe and Reno and he almost bought a Nevada ranch. Will Rogers was unique and helped people though the Great Depression. In this article we explore his connection to Nevada.

I do not belong to any organized political party. I’m a Democrat! That Will Rogers quote from 1924 will find its way out of the mouths and from the pens of political pundits as the nation moves closer to 2014 general election. It is a real challenge to think what the great American humorist and social commentator would say about today’s current affairs..

Even those of us who caught the stage production of the Will Rogers Follies in the 1990s might not have fully understood that he was one of Hollywood’s biggest stars in the 1920s and ’30s, making more than 71 movies in all; that he was the country’s first big radio personality; that for years he was its most widely read columnist, often getting play on the front pages of local papers; that he was so popular that Life magazine pushed him into a run for the presidency; that perhaps only Franklin Roosevelt helped the country spiritually through the Great Depression more than Will Rogers.

Far fewer folks—maybe only a handful, in fact—know that he also had a great deal of affection for the state of Nevada, particularly its southern tip. A world traveler and aviation pioneer, he flew into Las Vegas on his way home to Beverly Hills, and while here he often talked politics, never failing to bring up one of his all-time favorite agendas: the need to create of a dam across the Colorado River. He loved the American West, so he knew the value of the water supply it would create.

A promotional still from the 1930 movie “Lightnin'” starring Rogers. It appears this is the only Rogers film never re-released.

A Cherokee Indian from Oklahoma who first gained fame as a cowboy trick-roper, Rogers loved the West for its rugged rural character, and Nevada was one of the West’s most rugged and rural states, with a population of 91,000 in 1930—less than one person for every square mile. At the northeast end of the Mojave Desert, barely 5,000 people were living in the 25-year-old town of Las Vegas.

It was not just the openness of the geography that he was attracted to; it was the lack of hypocrisy. To Rogers, Nevada’s attitude toward life seemed as wide open as its spaces. Which is why, on August 31, 1930, millions of Americans picked up their morning paper and read these words in the “Will Rogers Says” column: “When you feel that the people around you are taking too much care of your private business, move to Nevada. It’s freedom’s last stand in America.”

Rogers was familiar with Southern Nevada, having passed through Las Vegas on many occasions after moving his family from New York to Hollywood in 1919. But it wasn’t until 1927 that Rogers made his first “public” trip through Las Vegas. He was on his way to the East Coast to set a record of sorts.

The end of May 1927 was when Charles Lindbergh rose from obscurity to international fame after making the first solo nonstop flight from New York to Paris. Rogers, who would later fly with Lindbergh at the controls, had been bitten by the flying bug when airplanes were little more than kites with motors. In the fall of 1927, he was trying to set his own aviation mark, not as a pilot but as a passenger. He wanted to be the first passenger to fly coast to coast and back again in the open cockpit U.S. Mail biplanes.

October 18 marked the real beginning of the humorist’s connection to Las Vegas. It was his first stop after taking off from Los Angeles, and he was on the ground just long enough to get gas and oil. Three days later, on the return trip of his record-setting journey, Rogers stopped long enough to put Las Vegas in his column for the first time. Here’s the dispatch that appeared in several hundred newspapers across America:

To the Editor of The New York Times: Las Vegas, Nev., Oct. 21—Had the greatest kick flying this morning I ever had. All the way across Wyoming we chased wolves and antelopes. Will be home for dinner. Left Tuesday morning, spent one night and a half day in New York City and back in Beverly Friday afternoon.

Have only been away three nights. If you had left Los Angeles on the train at the same time I did you wouldn’t even arrive there till Saturday morning, and, boy, what pilots those air-mail babies are. Lindbergh came from a great school. Yours, Will Rogers.

P.S. This Las Vegas you will hear a lot of it when Boulder Dam is built. We just flew all over and around it. It certainly should be built. The man that never saw it by air never saw it.

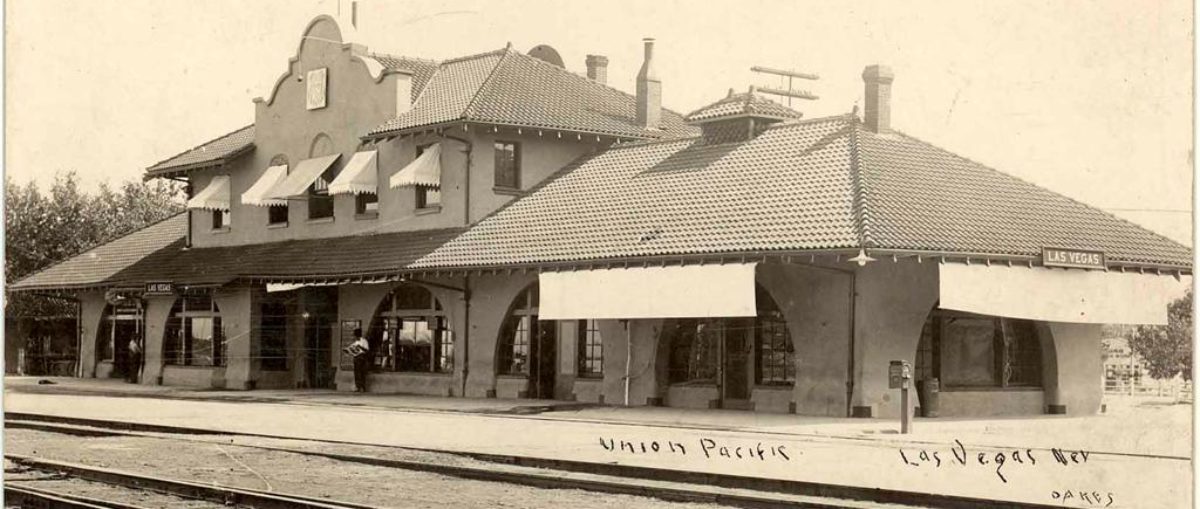

Rogers had entered Las Vegas air space shortly after noon. Following the aerial tour of the proposed dam site, Rogers landed on a dirt airfield. Located underneath today’s monorail station behind the Sahara Hotel, Las Vegas’ first “airport” was not much more than a piece of desert that had been leveled by dragging a section of a railroad track over it.

Rogers spent less than 30 minutes on the ground. He told the group gathered to greet him: “I want to tell you all that there’s just one way to travel: Take the air. It’s fast, it’s clean and now it’s safe. Boys, I’m comin’ back here again and give his damn town more attention.”

In the January 1928 issue of the Saturday Evening Post, Rogers wrote an article about his coast-to-coast air trip. In it he described Las Vegas as “a very pretty town that is a real oasis of several thousand people.” He added: “It’s a dandy little city and you will hear much of it. They got plenty of water and trees right out on the edge of the desert.”

Rogers, as he often did on his Sunday night radio show and in his columns, then promoted the idea of building the dam. At the time, legislation authorizing the project was tied up in Congress. Rogers said the dam “has to be built, for the Lord has already done most of the work, and this very Las Vegas is the place that will be the headquarters for all the work and workmen. You will see this name in many a dateline in the next few years.”

With his national magazine articles and radio shows promoting the dam and Las Vegas, Rogers became a hometown hero. And Las Vegans would see Rogers again soon, during the first and most significant of several trips here in 1928. That springtime visit would form a special bond with the community, one that was more than just an entertainer and his adoring fans; Rogers was about to become one of Las Vegas’ good old boys.

He flew in from Salt Lake City at 6:45 on the evening of May 3, 1928, and was greeted by a large crowd. Pioneer Las Vegas newspaperman C.P. Squires, along with a gaggle of Rogers’ admirers, convinced Rogers to stay the night and take in the American Legion fights. Rogers accepted the invitation, saying, “I like this place and the people.”

The audience in the American Legion Hall buzzed with excitement as Rogers walked in, and after the boxing matches, they insisted that he take a bow. Much to their surprise, he did a lot more than that. For more than an hour, Will Rogers entertained them.

He “kept the crowed in a roar,” Squires wrote, adding that it was “probably was one of the cleverest shows ever presented to an audience by Will Rogers, and it was done for the joy of life.” Fellow newspaperman Frank “Scoop” Garside agreed, pointing out that Rogers’ standard fee of $100 a minute would have cost the crowd about $8,000.

Garside, who owned what is now the Las Vegas Review-Journal at the time, took extensive notes that night. Among the highlights:

- Rogers introduced himself by saying, “I’m glad to be here with the American Legion boys. I didn’t do anything much in the war except stay home and take care of the [Ziegfield] Follies girls for you. I sure did that, and if you didn’t get a Follies girl when you got back it isn’t my fault. I saved ’em for you.”

- “I don’t know much about fighting. I make my living kiddin’ folks. I’ve been trying to kid the government into building that dam you folks want so bad, but so far it hasn’t done any good.”

- Rogers launched into presidential politics, which in 1928 featured Secretary of the Commerce Hebert Hoover running for the Republican nomination, and New York Governor Al Smith for the Democratic. “Now you Republicans,” Rogers told the Las Vegans, “I can’t pay you anything for votin’ tonight. I realize you are used to gettin’ paid for votin’ but tonight you’ll have to vote like Democrats. We’ve been votin’ for nothin’ all these years.”

- Rogers on Hoover: “I’m glad to see him running. We’ll find out how far a competent man can get in politics. It’s never been tried before. I was down in Mississippi when Hoover was there helping the flood victims,” and Hoover had “a lot of tough luck. Every time he’d save someone, he’d find out it was a Democrat.”

- “Y’know, I used to be a mayor of Beverly Hills, but I got kicked out. I started a reform movement; tried to limit the movie folks to two marriages a year, and they called me a Puritan. Then I tried to force the nightclubs to close at three o’clock in the morning; I claim if a guy can’t get drunk by three in the morning, he just ain’t tryin’—he hasn’t got his mind on his work.”

With the crowd calling for more, Rogers told his new best friends that he was hungry. Shaking as many hands as he could, Rogers left with the local newspapermen in tow and headed for the little Covered Wagon restaurant. Squires said it was a “rather shabby and primitive eating place,” but that “Will always insisted in stopping there and eating chili beans, lingering long at the little board counter to gossip with the boys.”

“How much better,” Squires thought, “to have the friendly humor of Rogers than the cutting satire of others.”

Rogers headed home the next day to get ready for another trip east to cover the presidential nomination conventions. The first leg was the Republican convention in Kansas City, and it would begin, less than a month later, with an unexpectedly dramatic moment in Las Vegas.

* * *

Rogers and his pilot flew back in a brand-new Lockheed Vega closed-cockpit monoplane. It was state of the art, and Rogers was considering buying one. The flight to Las Vegas was easier inside the new airplane and faster than the old mail planes but Rogers was still required to wear a parachute.

The new plane and Las Vegas landing strip were not a good match. The Rockwell Brothers owned the land the airfield sat on and had sold it to international industrialist Leigh Hunt. Hunt wanted to build a resort there, and the primitive airfield began to suffer from a lack of upkeep. Moments after the Rogers plane touched the desert dirt, one of its wheels hit a hole or a bump and gave way, spinning the plane and flipping it on its back. The pilot got out, but Rogers was left hanging upside down in his seatbelt.

Local newsmen rushed to the scene, and soon the word was flashed across the nation: Will Rogers in plane crash in Nevada. But as soon as Rogers was released from his shoulder harness and parachute, he crawled out unhurt. Asked by reporters if he was scared, he replied, “Scared? Why, boy, I wouldn’t a missed that for anything. That was more fun than I’ve had for a long time! The only thing wrong was I wish it was in Boulder Canyon, then I could a been the first one to land on his head and ears where they’re a gonna build that dam!”

For the scribbling journalists, he quipped, “I started for the Republican convention at Kansas City and landed in Las Vegas on my head.” Then he added: “What worries me most is that I had plenty of’ time to think up a good joke and didn’t do it. I’m fallin’ down on the job as a humorist.”

Rogers would continue to work on a “good joke” about his upside down Las Vegas landing.

Waiting for another plane to arrive, Rogers headed for town, followed by the reporters. After lunch, he asked to drive out to the proposed Boulder Canyon Project site. As arrangements were being made, Rogers noticed the town had been flooded with real estate brokers, which prompted him to take another stab at his joke: “We left California in good shape and landed in Las Vegas square on the heads of two real estate agents selling Boulder dam lots.”

He called them “binder boys,” after their counterparts in Florida, where land speculation and selling options were rampant. “I see there’s a lot of them here. Oh, you’ll have plenty o’ fun with ’em when they pass the dam bill. They’ll run y’ ragged.”

Shortly before Rogers was due to ride out to the Colorado River, word came that his replacement plane would soon arrive, so the excursion was canceled. Instead, he headed for Salt Lake.

The next stop after that was Cheyenne, Wyoming, where, moments after landing, the plane hit a gopher hole and, just like 24 hours earlier, flipped over on its back. This time reporters noted that Rogers’ shirt was bloodstained from cut behind the ear.

With two upside down landings Rogers was ready with a quote for reporters: “I started for the Republican convention and landed on my head in Las Vegas. Served me right. I should have gone to the Democratic convention.”

Just before the 1928 political conventions began, Life magazine started a campaign to put Rogers on the ballot. And he would run as the nominee of the “Anti-Bunk Party,” with supporters that included Henry Ford and Babe Ruth. But Rogers, whose run for the presidency was really just part of his act, eventually closed down his campaign before the election, saying, “The thing that stopped our party is that we are a hundred years ahead of times. “We went into this campaign to drive the bunk out of politics, but our experiment, while noble in motive, was a failure.”

Rogers, who often warned Americans about debt and speculation, had a clear view of the future when he told his readers: “No nation in the history of the world was ever sitting as pretty. If we want anything, all we have to do is go and buy it on credit. So that leaves us without any economic problems whatever, except some day to have to pay for them but we are certainly not thinking about that this year.”

Rogers would later add: “America is the only country where people drive to the poor house in their car.”

Herbert Hoover was elected president that fall, but the honor wouldn’t last long. The American dream began to crash with the stock market in October 1929, and the Great Depression that began in its wake would eventually put millions of Americans out of work, while hundreds of banks would close, as well as tens of thousand of other businesses. Hoover would take the fall.

Like always, Rogers’ humor didn’t take sides during this time: “Let’s stop blaming the President and the Republicans for all this. Why, they are not smart enough to have thought of all that’s been happening to us lately.”

Though a Democrat, Rogers actually did like Hoover. Maybe that had to do with the engineer turned civil servant’s dam loyalty. Itt was Hoover’s work first as secretary of commerce and later as president that was the driving force behind the dam project.

After a quarter-century of investigation and politics, the federal plan to build the massive dam across the Colorado River couldn’t have come at a better time for the country or Southern Nevada. While Rogers’ words of wisdom and warm sense of humor eased the pain of hard times in the early 1930s, he also—probably for a similar reason—continued to promote the construction of dam, which began in 1931.

After finishing the movie Too Busy to Work near Bishop, California, in fall of 1932, Rogers got in his car and headed for dam site. Arriving in Boulder City midday on September 5, Rogers toured both the town and the construction site before heading to Las Vegas.

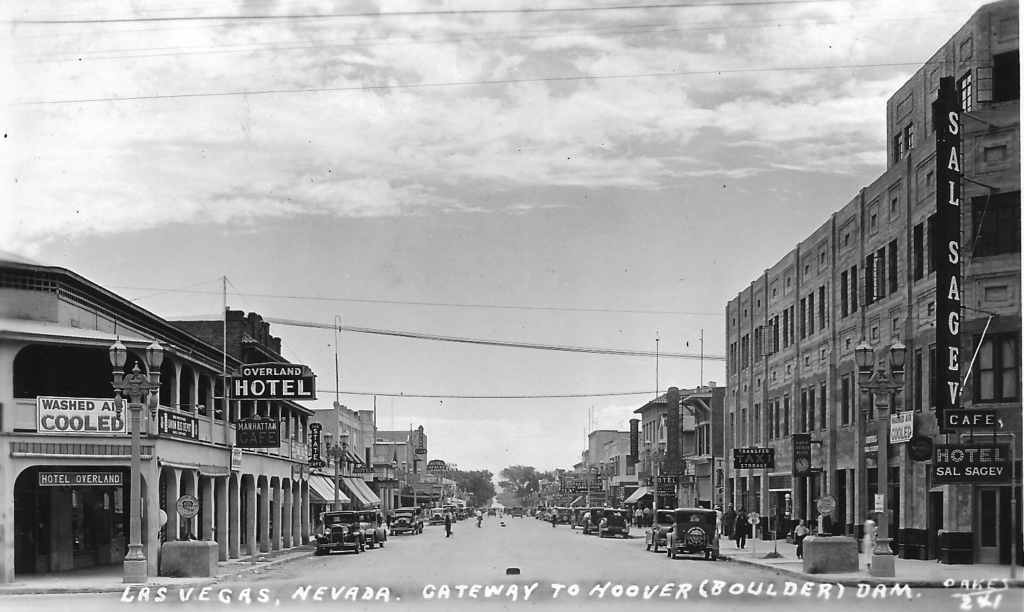

He spent the night at the Sal Sagev (now the Golden Gate).

An original 1932 photographic post card by Leon Oakes of Fremont Street including the hotel where Rogers stayed.

After touring the dam, the next day Rogers sent the following to his newspaper::

Don’t miss seeing the building of Boulder Dam. It’s the biggest thing that’s ever been done with water since Noah made the flood look foolish.

You know how big the Grand Canyon is. Well, they just stopped up one end of it and make the water come out through a drinking fountain.

It’s called the “Hoover Dam” now, subject to the election returns.

Two months later, Hoover lost to Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

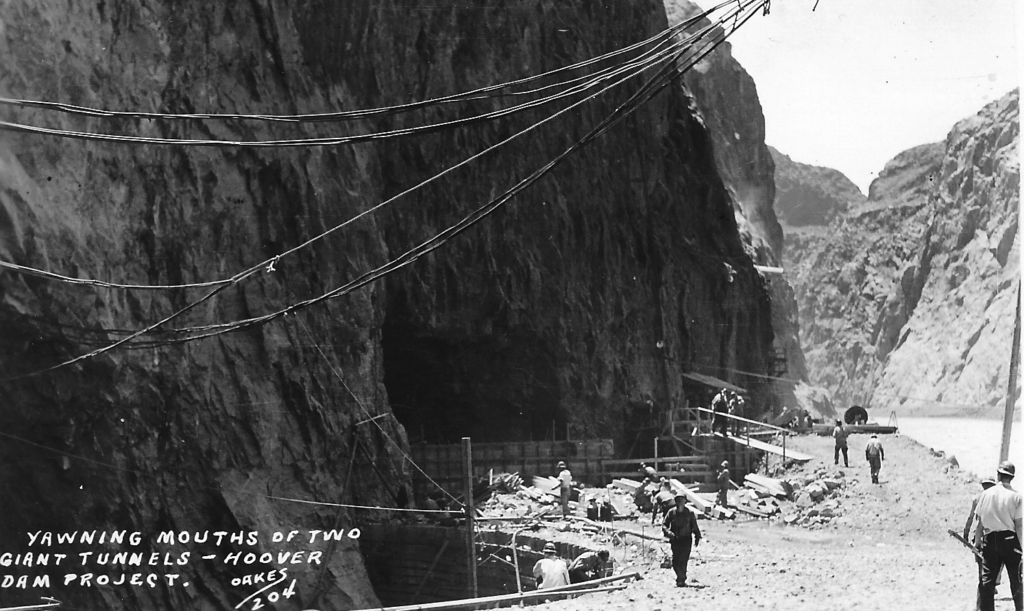

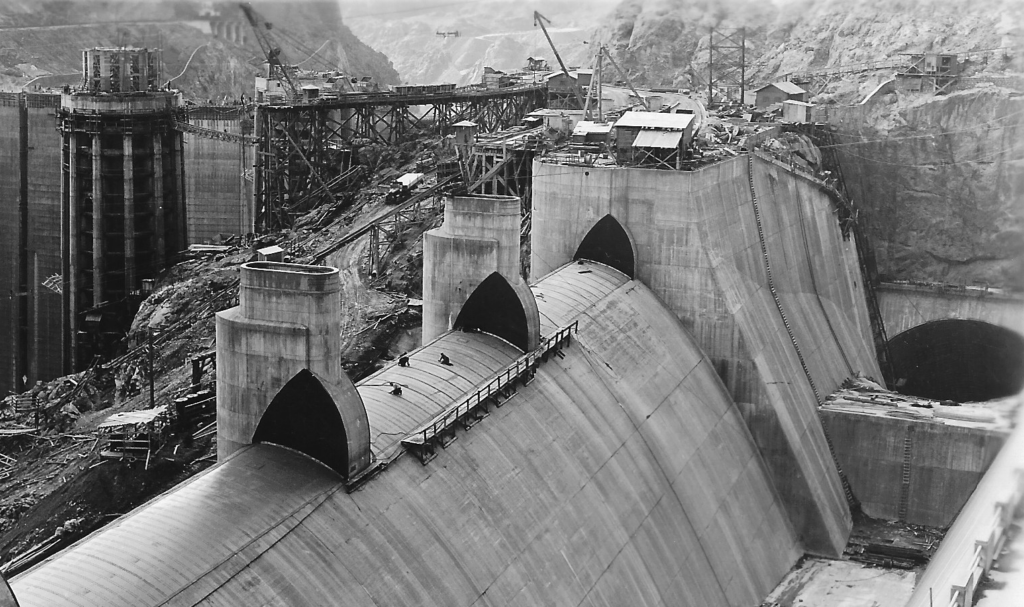

Workers at the dam during the early 1932 stage of construction. Note the post card uses the phrase “Hoover Dam Project.” Photogather is Leon Oakes.

As Rogers said the name of the dam was in fact, “subject to the election returns. Within a few months of being appointed, the Secretary of the Interior, By President Roosevelt, Harold Ickes changed the project’s name to “Boulder Dam.”

Rogers responded on May 14, 1933, telling his radio audience, “I see by the papers this morning that they are going to change the name of Hoover Dam. That is the silliest thing I ever heard of in politics. They are going to take the name of Hoover away from that dam.”

Rogers took his argument all the way to a dinner at the White House. When Rogers arrived he quickly discovered he was not the only one at the dinner with a sense of humor. A member of the President’s staff thought it would be fun to put Rogers at the same table with the new Secretary of the Interior Ickes.

“I had never met Mr. Ickes,” Rogers wrote in his column. “He is a mighty nice fellow and they claim very able. He and I picked up an old argument that we had differed on. I claim that it is the Hoover Dam. I am certainly glad the secretary of the interior didn’t leave his name on it and call it the Icke’s Dam.” [pronounced “ick-ee”]

As the dam was nearing completion in 1934, Rogers decided it was time for a road trip. Leaving Southern California early on the morning of October 18, Rogers and his wife, Mary, arrived in Las Vegas that evening. After spending the night, again at the Sal Sagev, the two headed for the dam, where they were given a personal tour by Frank Crowe, the project boss.

Crowe had a “sharp, dry wit,” Marion Allen, a longtime friend, recalled in his 1983 book, Hoover Dam & Boulder City. Allen wrote that, over lunch in Boulder City after the tour, Rogers had question after question for Crowe—How much did it cost? How big was it? And when Rogers asked Crowe how many men were working on the dam, Crowe replied, “Oh, about half of them.”

When Rogers toured the dam site in 1934 it looked like this. Photograph by Nell Oakes. Her husband, Leon, passed away in 1932, Nell, also a photographer was continued to record the construction of the dam though complete and was active though the 1940’s with her business “Vegas Studios.”

After Rogers’ brief visit to the dam and Boulder City, here’s what Rogers told the country the next day:

Mrs. Rogers and I started in on one of our periodical little automobile jaunts. We went away up to Hoover Dam and it’s the greatest sight in America today. I tell you, you ought to get in your car and drive by there before it gets finished. Fellow up there named Crowe, he is a real engineer, and some great men under him. You know, there is something about an engineer that, just about next to the medical profession, makes ’em about the most worthy folks we got.

* * *

By 1935, Rogers’ visits to Las Vegas were limited to pit stops on flights east or back home to California. But the Mojave was never far from his mind. “The more you see it the more you can understand folks really loving it,” he once wrote. “It’s a great health giver to many disabled soul. It’s just like a lot of folks that never had a chance. The minute you give it any water it grows more stuff than all your fertile land. Yes, sir, when I retire from active life, it’s the U.S. Senate or the desert, and, by golly, I believe I will go to the desert.”

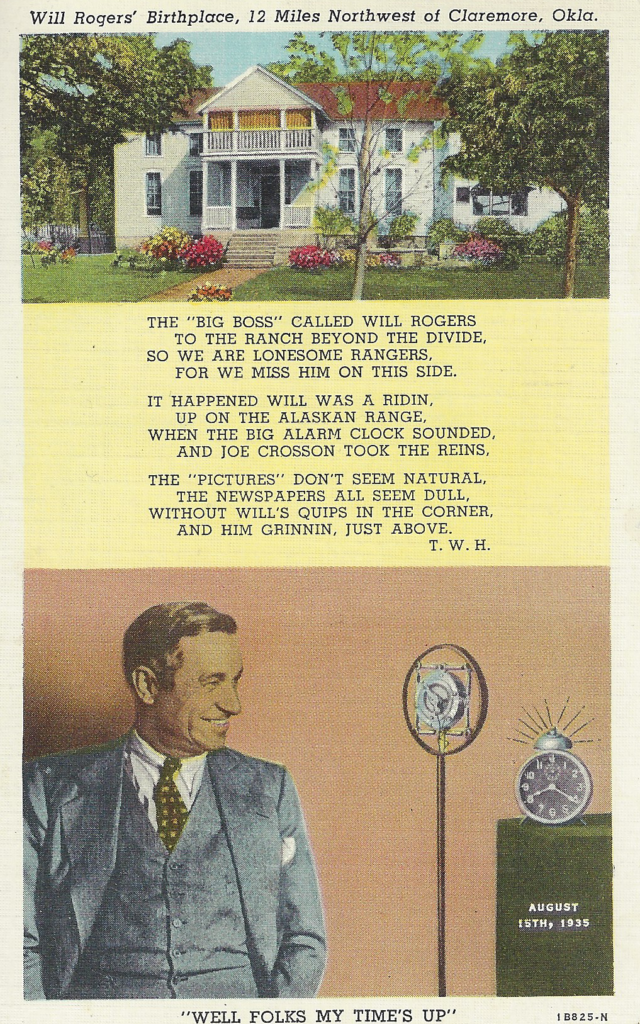

On July 29, 1935, with aviation legend Wiley Post as the pilot and Rogers and Mrs. Post as passengers, the three landed here for fuel on their way back to California from a vacation in New Mexico. It would be the last time Rogers would see Southern Nevada. Six weeks later, on August 15, 1935, Rogers and Post died in a plane crash in Alaska.

Rogers was 55 years old and at the top of his game, the most popular entertainer in the United States. And, Americans, just starting to see hope beyond the Depression, mourned him like no public figure since Abraham Lincoln.

“When Will Rogers died,” says movie historian Richard J. Maturi, and author of Will Rogers, Performer :, “America lost the voice that helped them through the Depression; it lost the voice that made them laugh and forget their troubles; it lost the voice of reason when others had an agenda; and it lost the voice of compassion for those less fortunate.”

When the news spread, Maturi says that ABC and NBC went off the air for 30 minutes, and more than 150,000 people paid their respects in person. In Las Vegas, people stopped by Al Cahlan’s newspaper, Las Vegas Review-Journal, to find out if it was true. When told yes, they would begin crying. “Never, in all my newspaper experience,” Cahlan wrote, “have I seen a whole people so moved by the passing of one individual. Presidents have died and not so touched the heart of the American Public.

“The reason is NOT hard to find,” Cahlan added. “Although successful beyond the fondest dreams of the average man, he never changed. He was always just plain Will Rogers, the Oklahoma cowboy who made good. There was no pretense or show about him. He was at home in any company, but preferred his old friends of the range. He could have been president, but he chose to be just himself. For Rogers was a great as was Abraham Lincoln, and as the martyred president, he was taken away when a suffering world needed him most.”

Six weeks after Rogers died, President Roosevelt arrived in Southern Nevada to formally dedicate Boulder Dam. But it was Secretary Ickes who, speaking before the president, felt the need to justify his idea to change the name from Hoover to Boulder Dam.

Speaking to a national radio audience, Ickes proclaimed, “As the eye encompasses the majesty of this work and comprehends the bold and rugged setting chosen for the taming of the water for the turbulent Colorado, the mind appreciates that this setting and this accomplishment … would not … fittingly be named by any less bold and striking designation than that of Boulder Dam.”

Will Rogers Highway

Will Rogers name would once again appear in downtown Las Vegas, when the famed highway, “Route 66,” alternate, 466 thought the dam created. From the dam, down the Boulder Highway, west on Fremont Street, then south on Las Vegas Blvd which was also U.S. Highway 91 and onto where 91 connected to Route 66.

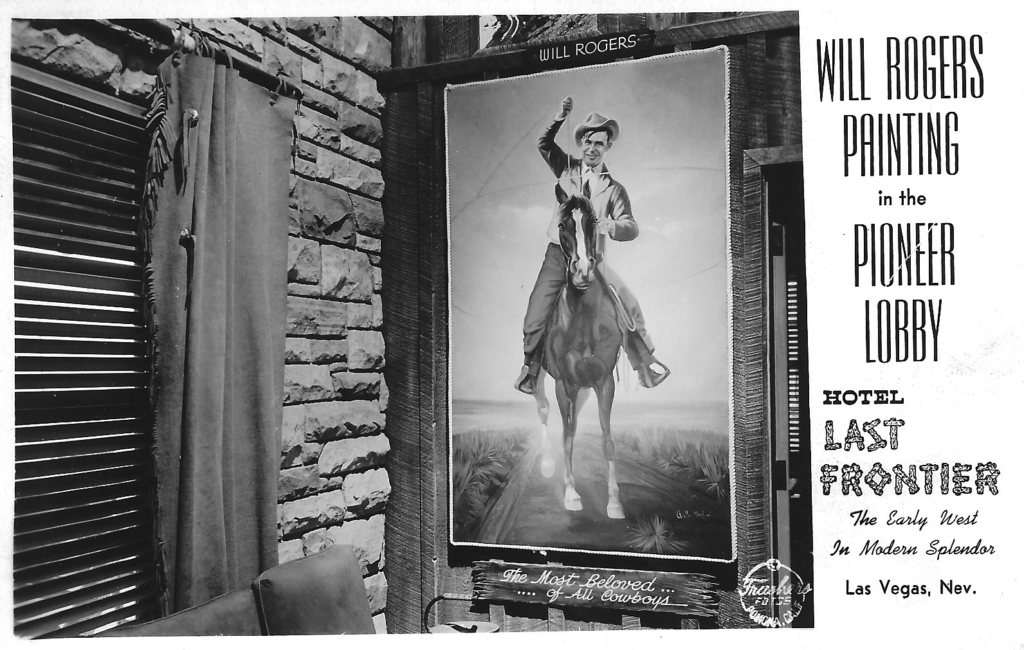

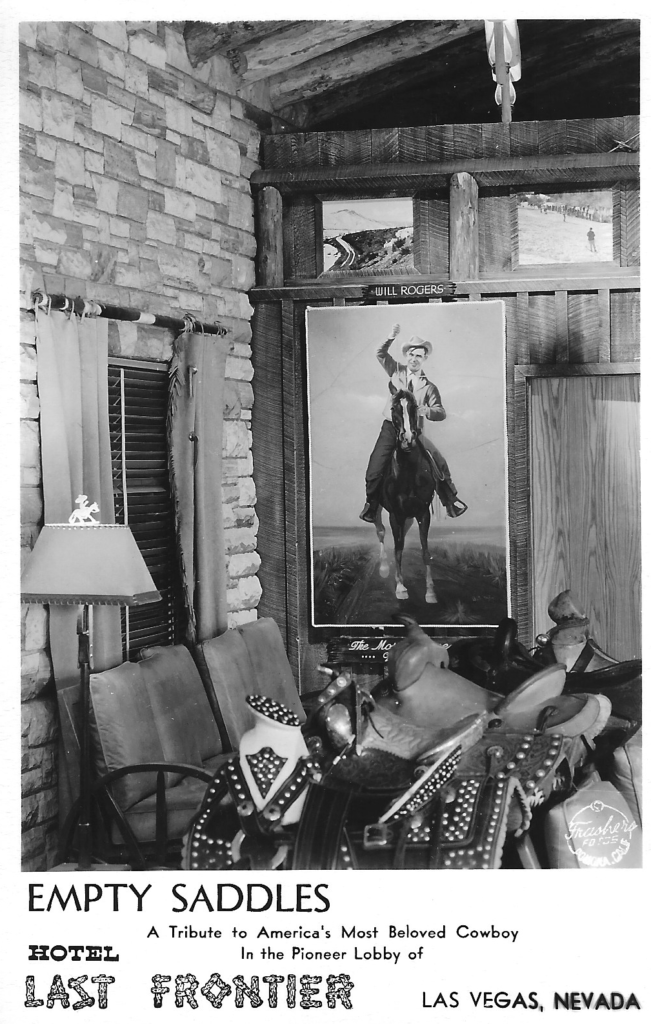

When the Hotel Last Frontier opened in 1942, Rogers was honored in the resorts lobby was “The Most Beloved of all cowboys.”

Even more fittingly, Rogers would have the last word in the feud. In 1947, with an act of Congress and a signature of President Harry Truman Boulder Dam once again became Hoover Dam.

Our next article on Rogers will take a look at his connection to the north, as it was Nevada as a whole state he liked; Rogers wrote in the fall of 1930: “When you feel that the people around you are taking too much care of your private business, move to Nevada. It’s freedom’s last stand in America. Yet they don’t do one thing that other states don’t do, only they leave the front door open. You can get a divorce without lying, a drink without whispering and bet on a game of chance without breaking even a promise.”

And why has Will Roger’s one movie, Lightnin’ filmed in Nevada, never been released.