In late 2017 the site of what is arguably one of the most historic gambling site fell into the deep hole of ‘Who Cares?’ Add to that, what history is available, is often buried in the fact-fantasy land of the internet.

Yet with names like the Stockers, the Stearns, and Siegel, the Northern Hotel Bar and Club in downtown Las Vegas has a fact based history that will surprise most. That includes the role the owners had in legalizing gambling in Nevada.

At this point there appears to be no effort on the part of todays’ operators of the property, or the Fremont Street Experience, or the City of Las Vegas to let locals and visitors know of the important and colorful history of this site and the rest of Fremont Street. (April 3, 2018 I’ve been quietly told, this will change. The when and how is still a question. But, at least the discussion has begun. Will stay on top of it.)

From the day the Northern Hotel and Bar opened in 1912 until he fled town, Lon Groesbeck operated both floors of the building. His energy was focused on money making possibilities of the first floor, alcohol and gambling.

Six years later, after Nevada and Clark county voters, in 1918 overwhelmingly approved legislation outlawing the sale of liquor, the future for Groesbeck, whose health was already failing, turned from clouded to clearly dark.

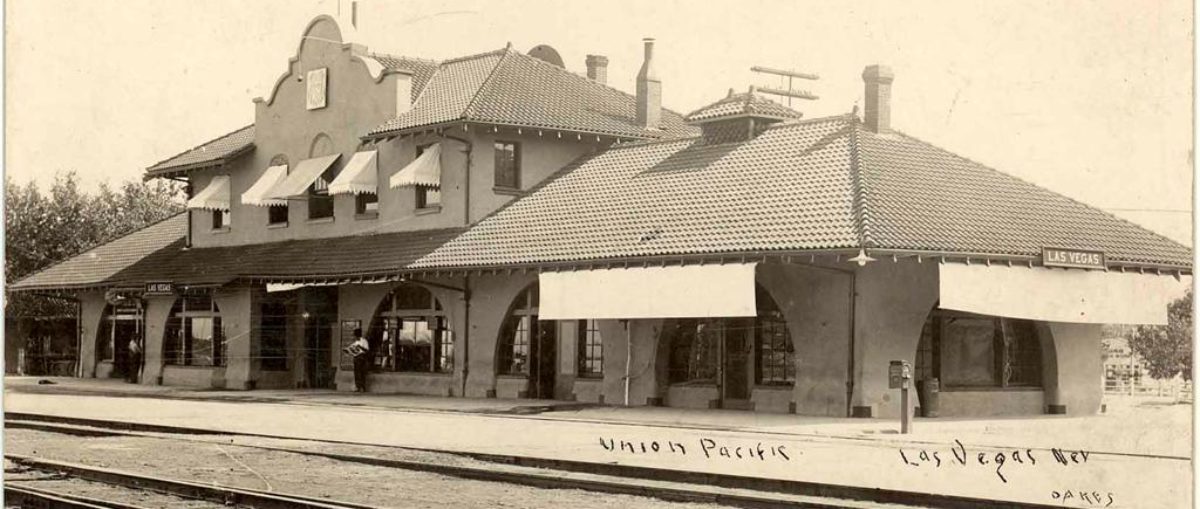

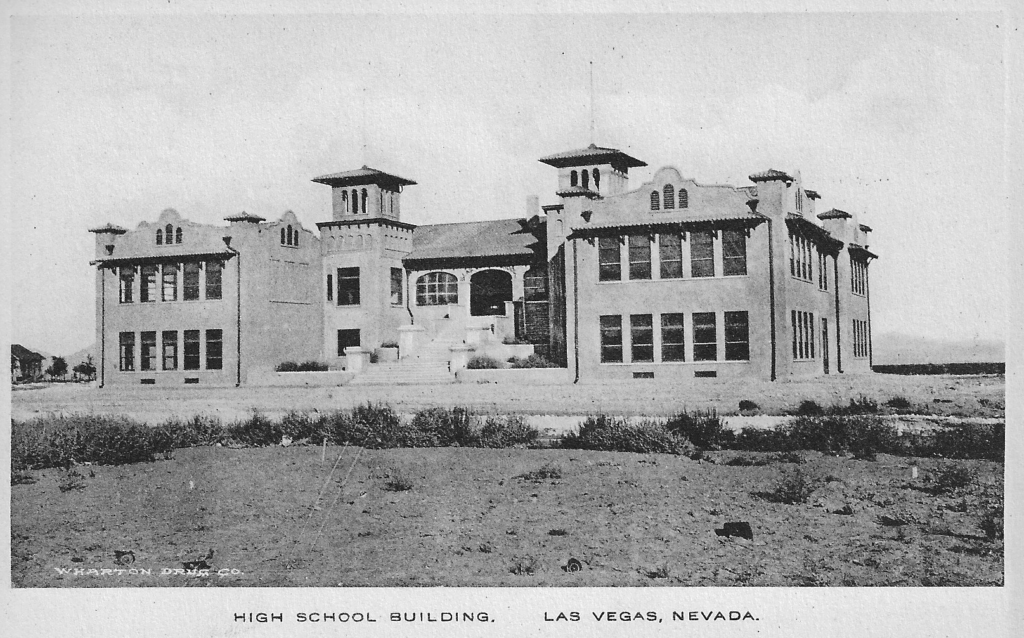

But when the Northern opened, like Las Vegas in 1912, it a welcome oasis on the northern edge of the Mojave Desert.

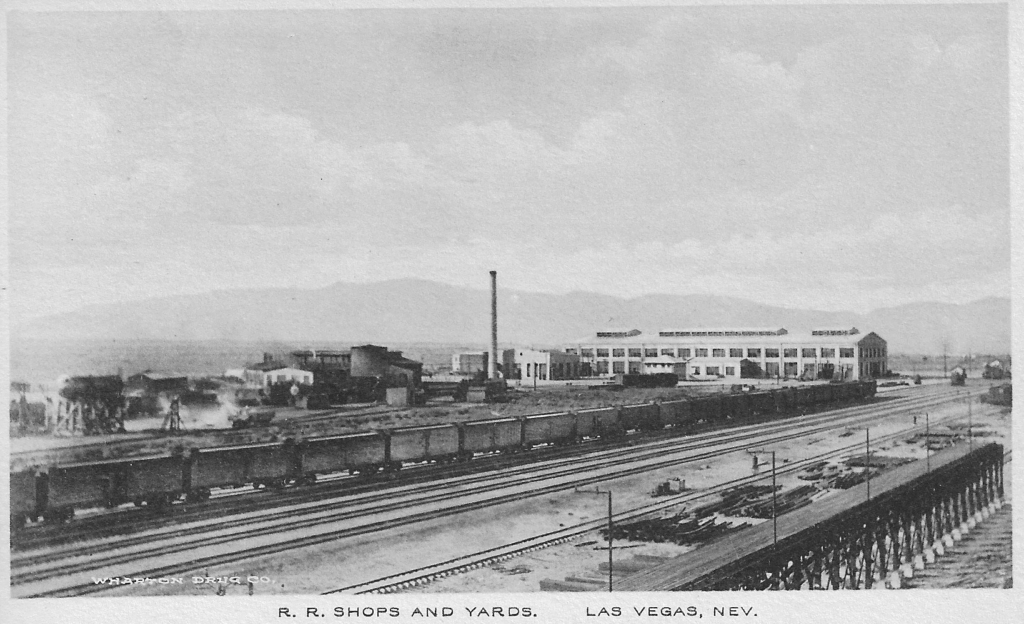

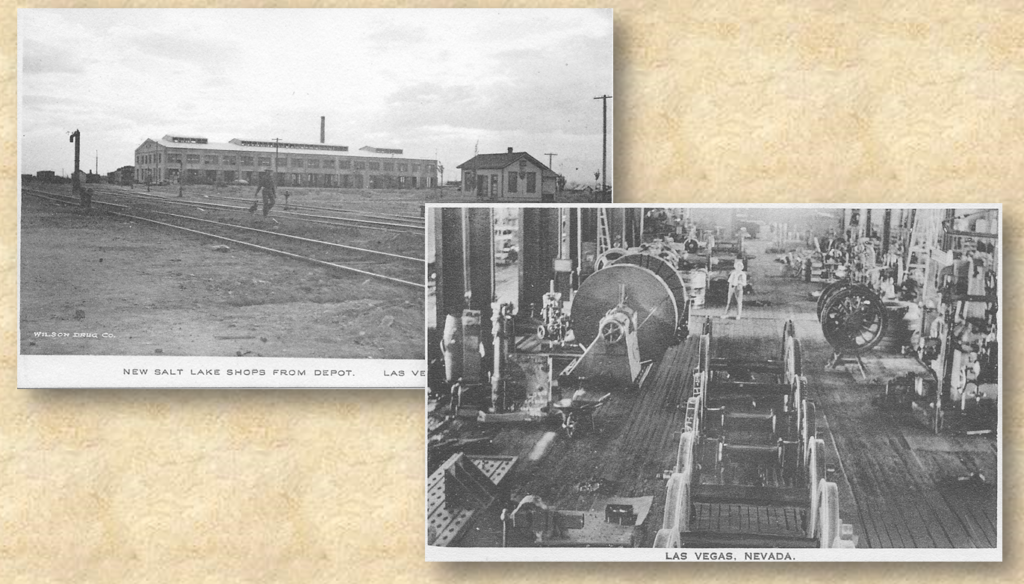

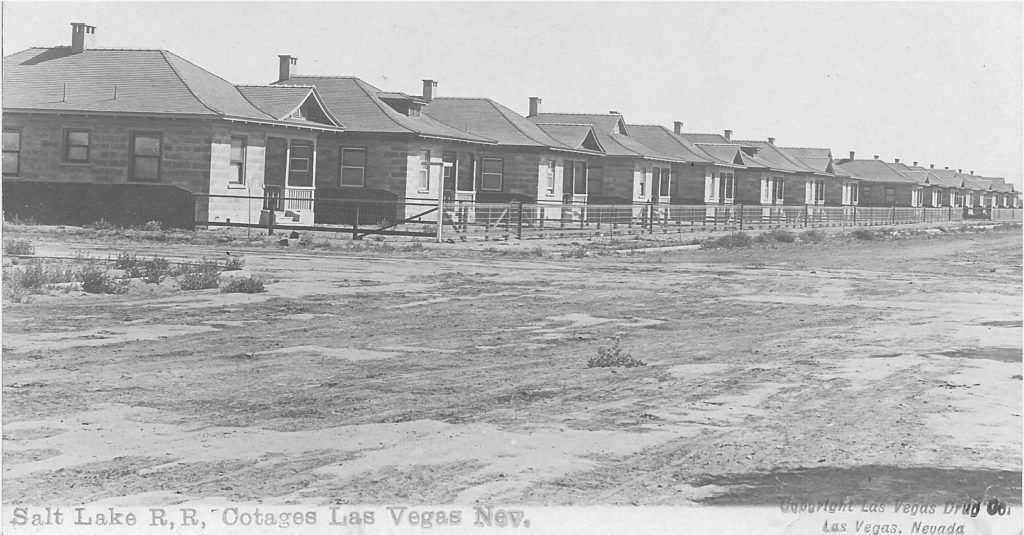

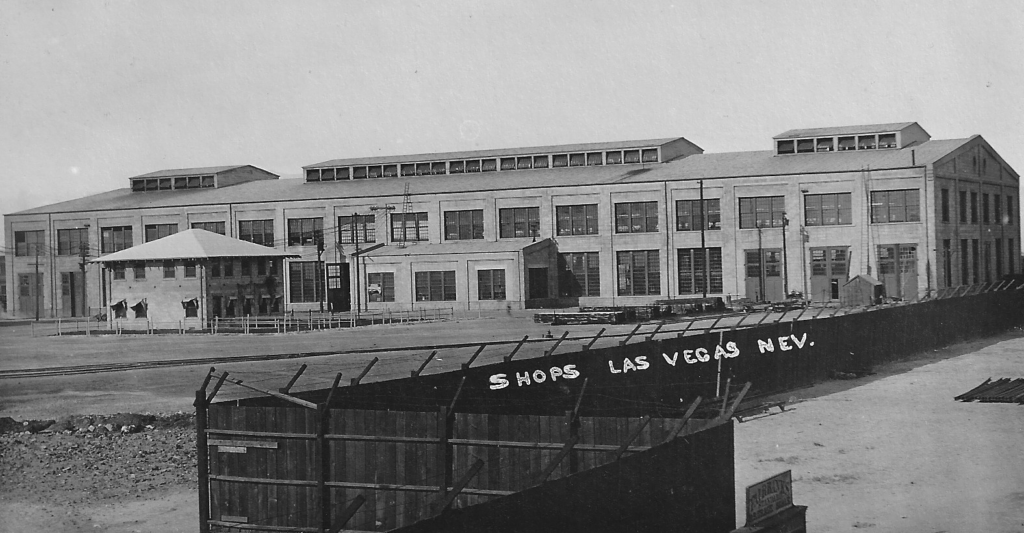

Las Vegas is also about half way between Los Angeles and Salt Lake City which, with the abundant of water at the time, made it an ideal place for a railroad to build a massive maintenance plant.

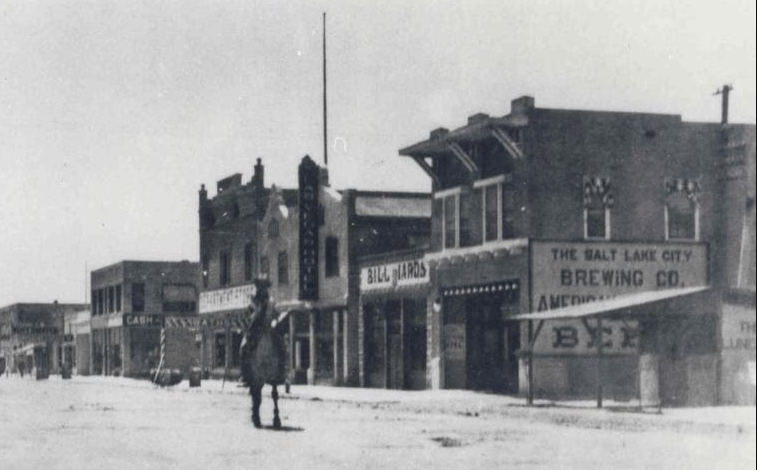

Las Vegas, 1912, Author’s collection

And with the plant hundreds of men came to Las Vegas, most of them single.

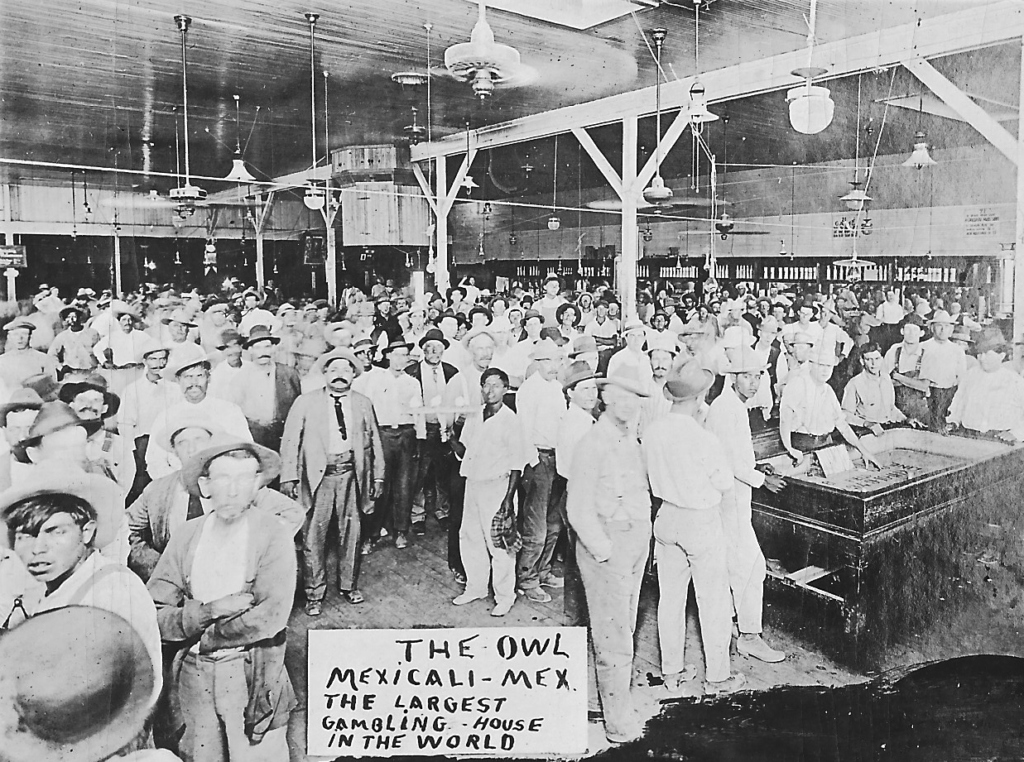

Despite the 1910 statewide ban on gambling, Las Vegas with its red light district-Block 16, (the east side of the 200 block of North First Street.) was at best a controlled “wide open town.”

After operating both floors for two years, in the late fall of 1914, Groesbeck transferred his “saloon license” to Fred Van Deventer.”

Details limited other than the transfer was approved by the Las Vegas City Commission. [i]

Then, not long after the town celebrated its tenth birthday there was a call to clean up the town both literally and morally.

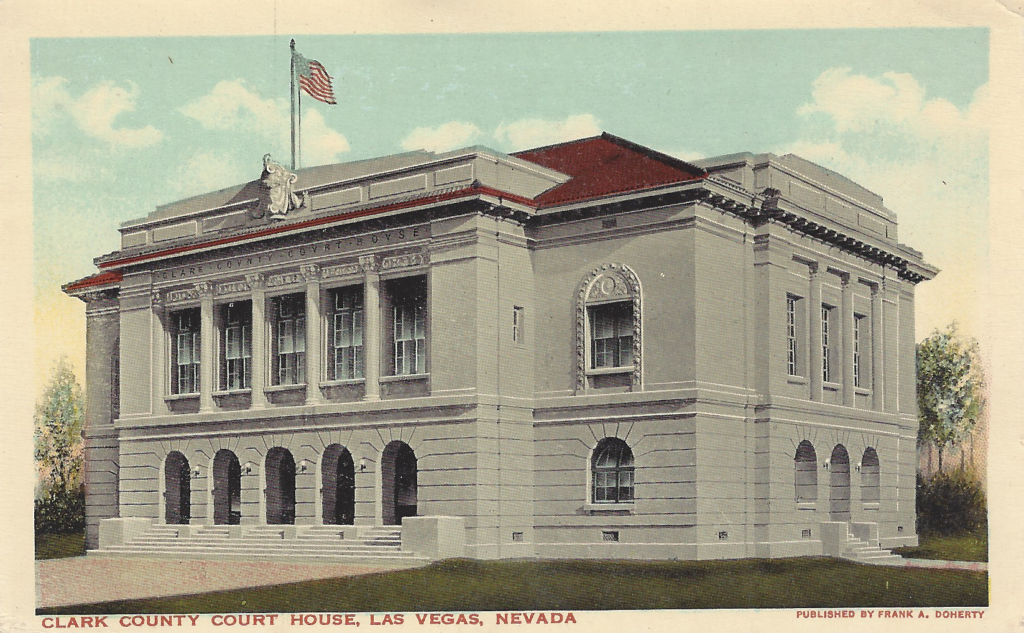

In May of 1916, Clark County District Court Judge Charles Lee Horsey convened a grand jury with specific instructions to look into vice and law enforcement in Las Vegas. Arthur Jerry Stebenne

In May of 1916, Clark County District Court Judge Charles Lee Horsey convened a grand jury with specific instructions to look into vice and law enforcement in Las Vegas. Arthur Jerry Stebenne

Judge Horsey would later become a Justice of the Nevada Supreme Court.

At the end of June, the grand jury issued its report. “Upon the subject of gambling” the report said “the neglect of duty on the part of peace officers, we have found for a long time past, illegal gambling has been openly conducted, with the knowledge of the peace officers who have made no effort to prevent the offense.”[ii]

And in regard to the sale of alcohol, still legal in 1916, the jury’s “Committee on Public Morales,” wrote, “We find upon investigation that for the years 1915 and 1916, 85%of the indigents were made such directly through indulgence in liquor and gambling.” [iii]

And, the grand jury did not stop at gambling and alcohol telling the judge “it is apparent that there are cases of illicit cohabitation in Clark County, particularly in Las Vegas and stringent laws should be enacted over this disgusting offense against public decency.” [iv]

The grand jury also handed down eight indictments for violations of the gambling laws.

Among those indicted was Groesbeck. He was charged with conducting an illegal casino operation at the Northern.[v]

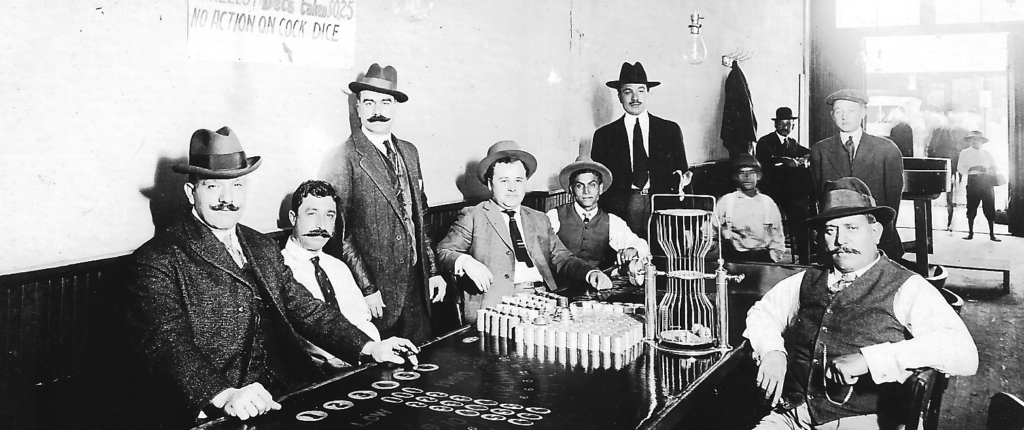

Groesbeck was specifically charged with taking a percent, a “rake-off” for setting up tables where men could play poker for money.

Groesbeck and his crew, which included early versions of “pit bosses,” ran the games.

Nevada state law at the time allowed people could gamble at poker, but did not allow the house to take a piece of the action.

A poker game at the Northern. The tables were all line up on the west side of the club, with the bar running north and south on the east side of the building.

Three months after he was busted Groesbeck was found guilty of allowing gambling at the Northern. The case, at the time, was described as under the new law the “first successfully prosecuted case against illegal gambling in Nevada.”

Clark County District Attorney, A. S. Henderson, in his colorful closing arguments compared Groesbeck to a spider; “When once a man is in its clutches it suck out his life blood. Like a spider, he grabs the fly and sucks the living blood out of him and leaves him to suffer the torments of hell. That’s what the gambler does, sucks the living blood until the man is fleeced of everything. [vi]

After Groesbeck was found guilty, the other defendants all pleaded guilty.

The next month, Judge Horsey sentences all six to one to five years in the state penitentiary in Carson City. But, with overall public opinion running against the “actual imprisonment of the offenders,” to the surprise of few the judge suspended sentence of each of the gamblers. [vii]

As far as Groesbeck, the Judge said, “I do not say, I have no sympathy for the defendant. I say, I have no sympathy for his business of far as his business relates to gambling. If I had the power” there “would not be any gambling in Clark county or anywhere else.”[viii]

With sale of liquor still legal Groesbeck went back to running the Northern Hotel and Bar for both men and for a while, for women.

The Northern catered only to men in the bar and the poker tables. In an effort to expand business “Six ‘wine rooms’ were established in the rear which ladies could patronize through a ‘family entrance’ off the alley.” [ix]

(We have been unable to find a photograph of women in the wine room or an image of the ‘family entrance’ to the Northern.)

A year after Groesbeck’s bust for gambling, he was in financial trouble.

In October of 1917, Liddie Groesbeck, his wife, (who lived in Salt Lake City) borrowed $2,800 from Fred T. Van Derventer, aka Fred Van Deventer.[x]

She agreed on October 17, 1917 to pay off the loan in fourteen equal payments of $200.

To “secure payment,” Mrs. Groesbeck put up “all the furniture, bedding, rugs, carpets and utensils of every description now in or about the second story of the building known as the Northern Hotel situate on Fremont Street between Main and First Streets,” also “the safe, desk, cash register and tables and chairs on the first floor.” [xi]

The loan document is signed only by “Mrs. Liddie Groesbeck” and says she “hereby acknowledge myself to be indebted.” [xii]

Ten days later, a notice appeared in the newspaper, “Fred VanDeventer has sold his interest in the Northern Hotel to Lon Groesbeck.”[xiii]

The changes at the Northern appear to be in preparation for the Salt Lake Brewing Company selling the land and the building.

Looking for a buyer in the middle of the winter of 1917, the company didn’t have to go far.

Fred and Nellie Cullen Leonard, who owned several business in Utah, would become the short term owners.

Leonard, in 1912, was the brewing company’s key representative in Las Vegas. He negotiated the deal for the brewing company to buy lot 27 in Block 3.

In addition to beverage, candy and hotel operations the the Leonard’s owned the Cullen Investment Company of Salt Lake City which became the new official owner of record of the Northen. [xiv]

Initially, the Leonard’s kept their friend Groesbeck on as manager of the property. That would soon change.

At its first meeting in 1918, Groesbeck asked the Las Vegas City Commission to transfer the “retail liquor permit” back to him from Fred Van Deventer. The request was approved. [xv]

Groesbeck resumed control of both floors of the Northern.

Weeks later, Van Deventer moved to Long Beach with his family. Instead of opening a bar, Van Deventer was reported “doing his bit” for the war effort in a “shipbuilding plant.” [xvi]

The last half of 1918 was a challenging for Las Vegas and its’ residents and would begin Groesbeck end.

Las Vegas ca. 1912, looking west from First and Fremont Streets. Author’s collection. The Northern is seen on the left side half way up the street with the extension from the top of the second floor.

Hit hard by the flu that killed millions around the world, dozens died in Las Vegas.

Many of the community’s young men had been drafted and were in France fighting in World War One.

And in November, the issue of banning the sale of alcohol was on the ballot.

In Las Vegas the question of whether to elect a sheriff who would enforce any such ban, or one whose record as sheriff was soft on the saloon crowd was also on the ballot.

As campaigning started, the flu epidemic hit Las Vegas.

By the time it was over the epidemic became a pandemic, killing millions of people around the world. More than fifty deaths were recorded in the small community of Las Vegas with an estimated population of less than 25-hundred.

Business was bad, travelers stayed on trains that were passing through Las Vegas, school were closed, sick people were confined to their homes, political rallies cancelled.

For the most part, local newspapers reported the 1918 election was quiet.

The most noise came from the ‘wet’s and the ‘dry’s battling over the question of banning the ‘booze.’

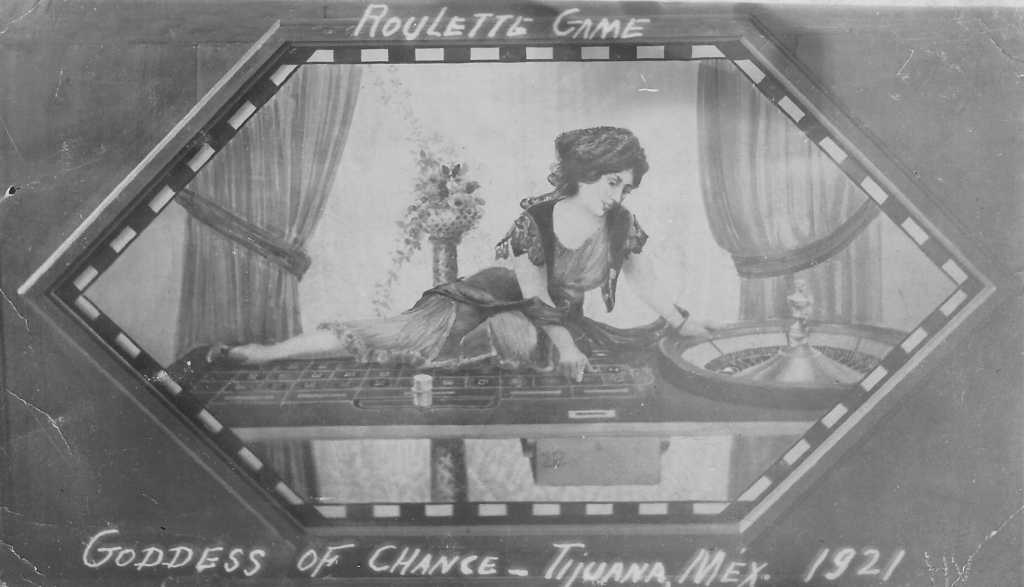

Post card cartoons of the day carried the message.

When the votes were counted in Las Vegas, Clark County, and the state, 22,308 people voted on the prohibition initiative.

Statewide 59% of the voters cast their ballots in favor of the statewide ban.

In Clark County the ‘drys’ whipped the ‘wets’ by a 69% to 31% margin. In Las Vegas the vote was similar, 63% in favor of the ban to 37% against.

On the flip side, voters elected former sheriff Sam Gay, a former bouncer in the red light district, who had been forced out of office earlier.

For a few days after the election and into the New Year it was still easy to get a drink at the Northern and other saloons, but slowly liquor went under the bar and into the back room.

Saloons along bock 16 began closing their doors and reopening as soft drink parlors. But there was little trouble in securing liquor.

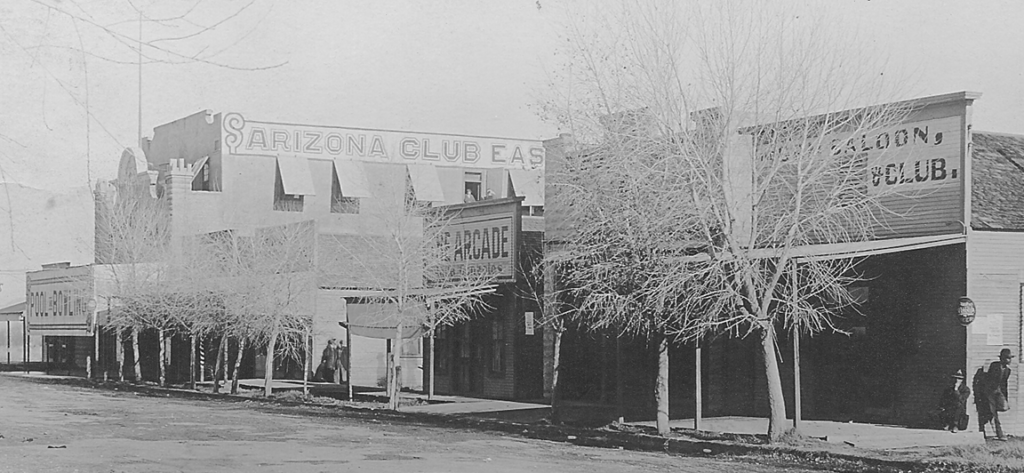

Saloons were located along Block 16 with the two-story Arizona Club leading the pack. Author’s collection.

Saloons were located along Block 16 with the two-story Arizona Club leading the pack. Author’s collection.

The hotel “bars” along Fremont Street were, less public about their illegal offerings.

Sheriff Gay, recalled, once “the church folks got busy and voted” for the ban, “me being Sheriff, had to dry the town up. So I sent around word to all the barkeeps to close or start selling buttermilk. And all but one did. I had to go in and help drunk up what he had left.”[xvii]

The Sheriff also took out an ad on the front page of one of the local newspapers; “I am going to enforce the prohibition law to the letter,” starting on January 6, 1919.[xviii]

He added a warning, “Mr. Bootlegger t his is your first and last notice from me. Your next notice will be a warrant of arrest.” [xix]

his is your first and last notice from me. Your next notice will be a warrant of arrest.” [xix]

Six weeks later, Sheriff Gay would make his first arrest under the new law.

But, it was not a local person. The suspect, A. P. Chamberlin, had just driven into town from Utah and got a room at the Northern.

The Sheriff went to Chamberlin room in hotel, found several bottles of bonded whiskey and arrested the out-of-towner.

Chamberlin was found guilty on February 26 and sentence to 90 days in jail and fined $125 and court costs and left town.

Through the rest of 1919, the saloons, said Sheriff Gay, “The town was dry for a year” he said “there was “no bootlegging then.” ”[xx]

While there were no desert stills, not yet, the Sheriff said the liquor that was sold came secret stashes left over from before the Nevada ban,as well as alcohol brought in from states where it was legal.

While the sheriff thought the town was ‘dry’ most would have described it if not ‘wet, a least very ‘damp.’

Reflecting on 1919, the Las Vegas Age reported, there were people “who have been almost openly, and notoriously selling whiskey in this city.” [xxi]

When the next bootlegging arrest was made, it was the district attorney, not the sheriff who filed the charges.

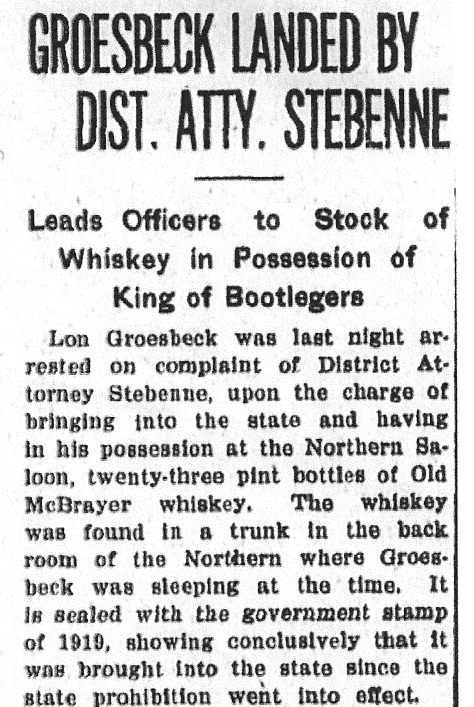

On the evening of Friday, January 2, 1920, Clark County D. A. Arthur Jerome Stebenne led a raid on the Northern to find the “King of the Bootleggers.”

Unable to find Sheriff Gay, the Stebenne secured the services of a deputy sheriff and the Las Vegas Constable.

Arriving at the Northern they found Sheriff Gay was already there. The D.A. “demanded” Gay participate in the raid. [xxii]

The four law enforcement officers found Groesbeck in bed in a back room of the first floor. [xxiii]

A half empty bottom of whiskey was in plain sight. Groesbeck, according to published reports, pointing to the bottle, told the four lawmen, “There is all I have, you can use that against men if you want to.” [xxiv]

But the D.A. said he had information that there was more whiskey.

At which point, Groesbeck got out of bed and opened a nearby trunk containing twenty-three pint bottles of McBrayer whiskey. [xxv]

Las Vegas Age January 3, 1920, page one.

Calling Groesbeck the “King of Bootleggers” Squires wrote in the Age, “the illicit sale of whiskey has been going on in this city ever since the prohibition amendment went into effect. Groesbeck has been suspected of being the chief violator of the law. It has been common knowledge that whiskey could be secured there by paying the price. Numerous cases of drunkenness have been traced to whiskey secured at the Northern.”[xxvi]

A few days later, Groesbeck pleaded guilty to “the charge of having whiskey in his possession. He was fined $400 and court costs of $22.50 and to serve three months in the county jail. The judge suspended the sentence if Groesbeck paid the fine and left town.

Groesbeck paid the fine and quickly left town.

But the district attorney, working quickly, forced a change in the suspended sentence and ordered Groesbeck arrest. In the few hours between paying the fine and the district attorney getting the jail time reinstated, Groesbeck left for Utah. [xxvii]

At the end of year Las Vegas newspapers were reporting on Groesbeck death in Salt Lake City. He was 62.

When Groesbeck fled town early in 1920, and with both alcohol and gambling illegal, it was the Cullen Investment Company turn to begin looking for someone to take over the Northern.

Groesbeck, before he left town, told authorities he had leased the gaming operations to James Germain.

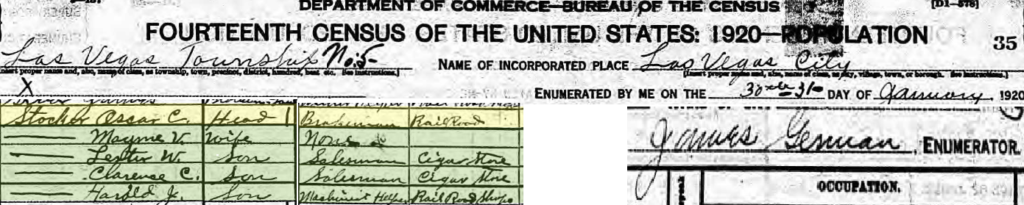

At that moment, January, 1920, Germain aka German had another job, the official Las Vegas Enumerator for the 1920 U.S. Census.

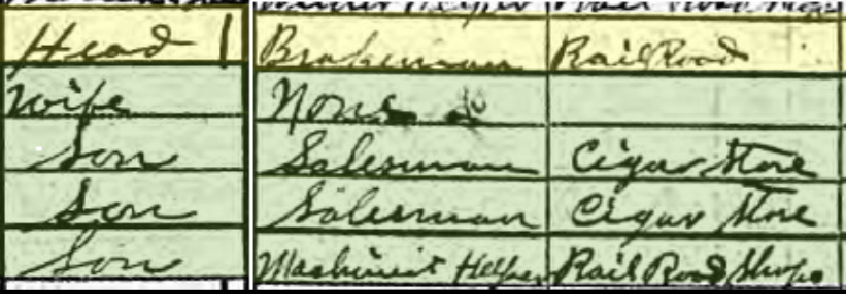

At the end of January, 1920, he interviewed the Stocker family and filled out the census forms for the five members of the family. [xxviii]

The five Stockers were Oscar the father and his wife Mayme, and their three sons, Lester, Clarence and Harold.

Oscar listed his occupation as a “brakeman” with the railroad, which would be the Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad, also known as the “Salt Lake Route.” [xxix]

When it came to Mayme “none” is listed under occupation. [xxx] Under the 1920 Census guidelines given to German Rule 158 says, “in the case of a woman doing housework in her own home and having no other employment the entry should be “none.”

Both Clarence and Lester listed their “occupation” as “salesman” in a “cigar store.” [xxxi]

And, finally, Harold, like his father was employed at the rail yards. He was listed as a “Machinist Helper.” [xxxii]

Before 1920 called it a day, the Stocker family would begin a nearly century long relationship with lot 27 of Block 3 of Las Vegas.

Coming up, Chapter three. The Stocker Era Begins. ‘Three wild and crazy guys!” arrive in Las Vegas.

[i] “City Board,” October 10, 1914, Las Vegas Age, Page two.

[ii] “Grand Jury Indicts Nine for Gambling,” June 10, 1916, Clark County Review, Pages one and three

[iii] “Grand Jury Indicts Nine for Gambling,” June 10, 1916, Clark County Review, Pages one and three

[iv] “Grand Jury Indicts Nine for Gambling,” June 10, 1916, Clark County Review, Pages one and three.

[v] Grand Jury Indicts Nine for Gambling,” June 10, 1916, Clark County Review, Pages one and three.

[vi] “First Gambling Case Results in Conviction,” September 30, 1916, Clark County Review, page one.

[vii] “First Gambling Case Results in Conviction,” September 30, 1916, Clark County Review, page one.

[viii] “First Gambling Case Results in Conviction,” September 30, 1916, Clark County Review, page one.

[ix] “Poker, Whist, Bridge Only Games Allowed in 1st Gambling Club,” May 16, 1948, Las Vegas Review-Journal & Age, Section B, Page four.

[x] “Chattel Mortgage,” between Liddie Groesbeck, and Fred T. Van Derventer,” October 17, 1917, Clark County Recorder Office, Las Vegas, Nevada document 10829.

[xi] “Chattel Mortgage,” between Liddie Groesbeck, and Fred T. Van Derventer,” October 17, 1917, Clark County Recorder Office, Las Vegas, Nevada document 10829.

[xii] “Chattel Mortgage,” between Liddie Groesbeck, and Fred T. Van Derventer,” October 17, 1917, Clark County Recorder Office, Las Vegas, Nevada document 10829.

[xiii] “Local Notes,” October 27, 1917, Las Vegas Age, page three

[xiv] “Groesbeck landed by Dist. Atty. Stebenne,” January 3, 1920, Las Vegas Age, Page 1.

[xv] “Regular Meeting of City Commissioners,” January 5, 1918, Las Vegas Age, Page one.

[xvi] “Local Notes,” May 18, 1918, Las Vegas Age, Page three.

[xvii] “The old west live, Las Vegas, A desert bloom,” 1930, Illustrated Daily News. Clipping, no page number.

[xviii] “Sheriff-elect gives notice and warning,” January, 1920, Las Vegas Age, Page 1.

[xix] “Sheriff-elect gives notice and warning,” January, 1920, Las Vegas Age, Page 1.

[xx] “The old west live, Las Vegas, A desert bloom,” 1930, Illustrated Daily News. Clipping, no page number.

[xxi] “Groesbeck landed by Dist. Atty. Stebenne,” January 3, 1920, Las Vegas Age, Page 1.

[xxii] “The ‘Northern’ In liquor raid,” January 3, 1920, Clark County Review, Page one.

[xxiii] “The ‘Northern’ In liquor raid,” January 3, 1920, Clark County Review, Page one.

[xxiv] “The ‘Northern’ In liquor raid,” January 3, 1920, Clark County Review, Page one.

[xxv] “The ‘Northern’ In liquor raid,” January 3, 1920, Clark County Review, Page one.

[xxvi] “Groesbeck Landed By District Atty. Stebenne,” January 3, 1920, Las Vegas Age, page one.

[xxvii] “Lon Groesbeck Flees From Jail Sentence,” January 10, 1920, Las Vegas Age, Page one.

[xxviii] 1920, United States Federal Census, Place, Las Vegas, Clark, Nevada, Roll: T625_1004; Page 23A; Enumeration District:3 .

[xxix] 1920, United States Federal Census, Place, Las Vegas, Clark, Nevada, Roll: T625_1004; Page 23A; Enumeration District:3 .

[xxx] 1920, United States Federal Census, Place, Las Vegas, Clark, Nevada, Roll:T625_1004;Page 23A; Enumeration District:3 .

[xxxi] 1920, United States Federal Census, Place, Las Vegas, Clark, Nevada, Roll:T625_1004;Page 23A; Enumeration District:3 .

[xxxii] 1920, United States Federal Census, Place, Las Vegas, Clark, Nevada, Roll:T625_1004;Page 23A; Enumeration District:3 .

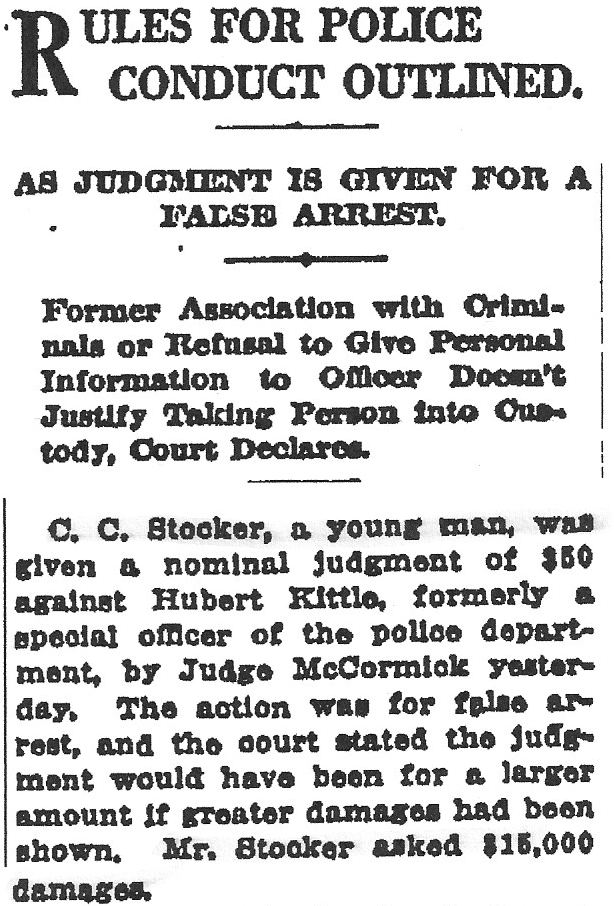

Los Angeles Times April 10, 1917

Los Angeles Times April 10, 1917