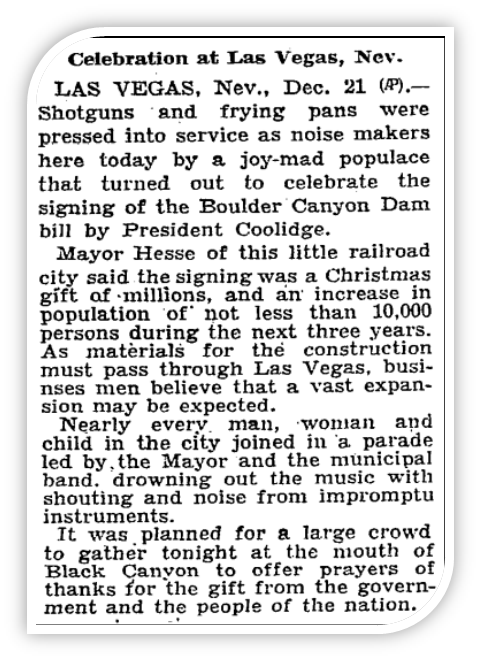

Chapter Three.

(updated April 3, 2018)

The Northern -To be Owned by the Stockers….including 3 “wild and crazy guys” aka “My Three Sons!”

In 1903 the land where lot 27 of Block 3, of “Clark’s Las Vegas Townsite,” would be located was owned by pioneer, Helen J. Stewart.

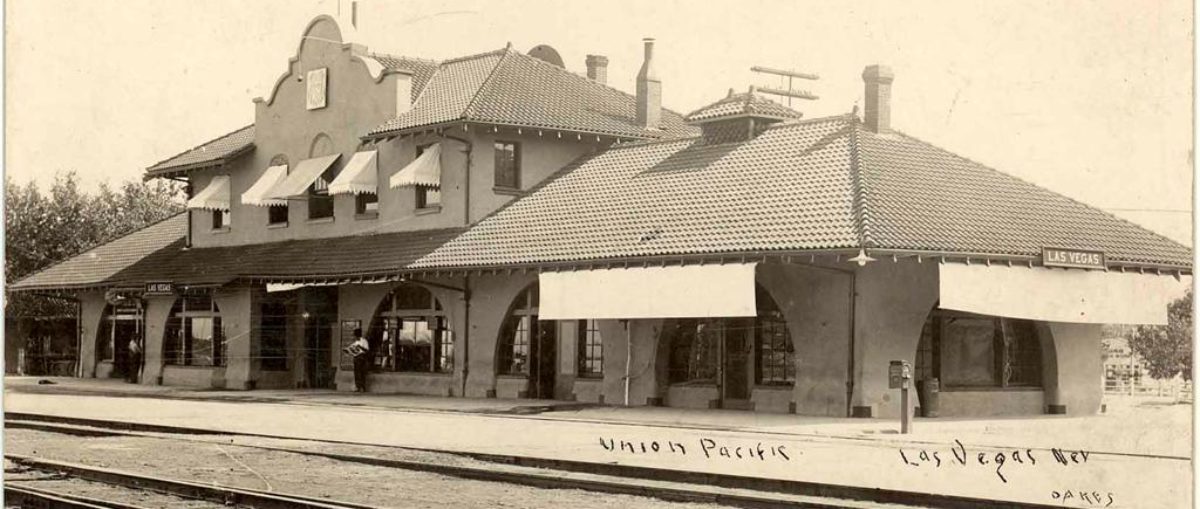

That year she sold the land to U.S. Senator William A. Clark. The Senator and the Union Pacific were building a railroad between Salt Lake City and Los Angeles.

The land then became jointly owned by Senator Clark and U.P.

In May of 1905, the railroad sold lot 27 of Block 3 in a land auction. J. F. Dunn, Superintendent of the Oregon Short Line railroad, which is part of the Union Pacific system, bought the lot.

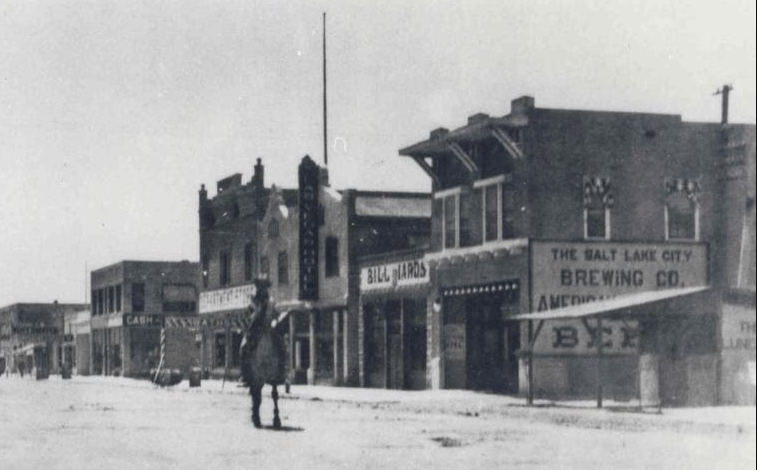

In turn the Salt Lake Brewing Company, in 1912, bought the lot from Dunn. The new owners built a two-story structure and named it the Northern Hotel and Bar.

The brewing company owned it for five years and then sold it to the Cullen Investment Company of Salt Lake City.

Cullen was owned by Fred and Nellie Leonard, who helped broker the original deal between the Dunn and the beer company.

Then on the 21st of October, 1921 Oscar C. Stocker bought the property.

Stocker paid $12,000 for the building and land.

In addition to the land and the building, the transfer deed also contained the language of the original railroad deed. This would allow the owner to sale alcohol, if and when it became legal again.[i]

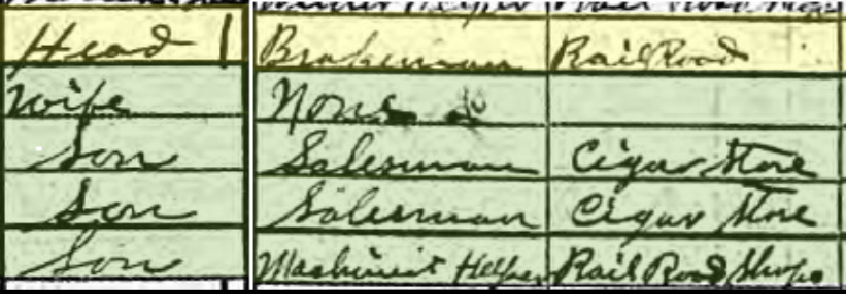

At the time, the 48-year-old Stocker was a brakeman on the Salt Lake Route railroad.

His wife was Mayme and they had three sons, Lester, Clarence and Harold.

A number of internet sites estimate $12,000 in 1921 is equal to more than $150,000 in 2018.

How Oscar was able to save up or where he got the money is still a question.

Lester had just gotten out of prison, Clarence had been working as a clerk in Los Angeles, and Harold said he had to take a job in 1919 in Las Vegas as a machinist; saying he needed money, “I had to eat.”

A simple mortgage arrangement with the Cullen Investment Company is possible, however, often those were part of the deed transfer. In this case no mortgage is attached to the agreement.

While the sale was finalized in October of 1921, it is clear by late in 1920 members of the Stocker family were “proprietors” of the Northern.

From that point on, the Stockers would all play a significant role in the history of the Northern, Las Vegas, and the development of legal and illegal gambling for several decades.

Who were the Stockers?

Looking for every note that may turn into a nugget as to who and why the Stockers would turn out to be “colorful,” we found contradictions, interesting memories, and a series of facts that turned out to be fiction.

We start first with when the family arrived in Las Vegas.

That date is questioned by Stockers themselves. It was either 1910 or 1911.

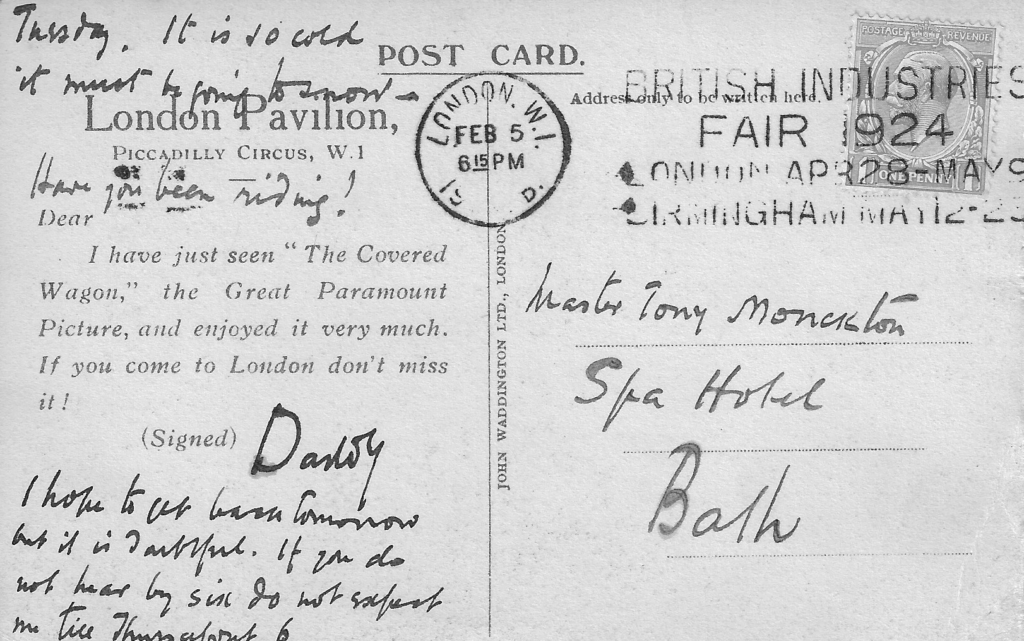

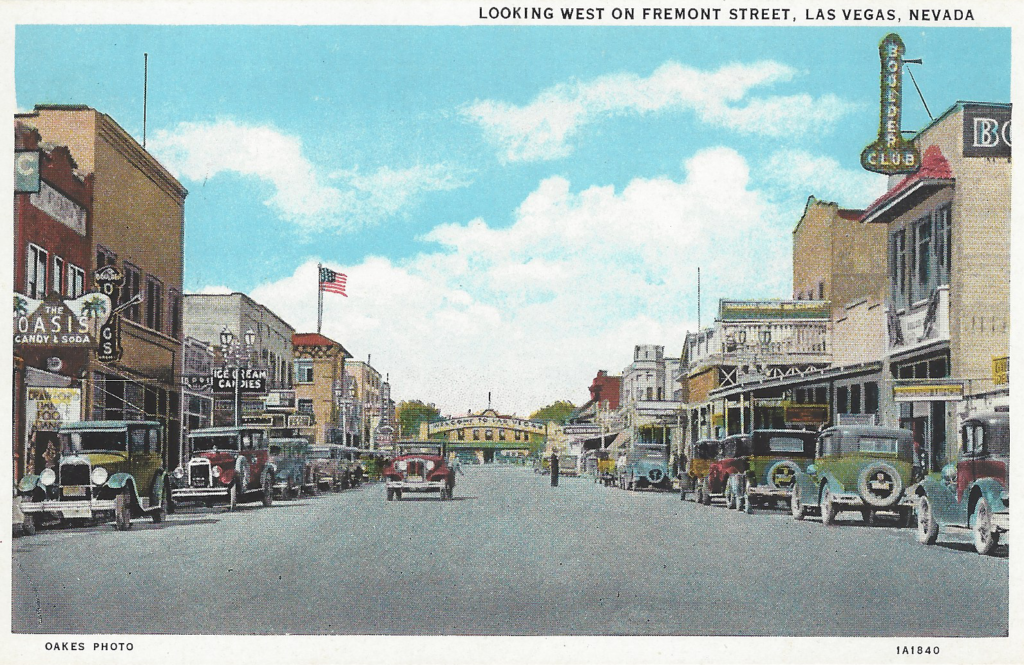

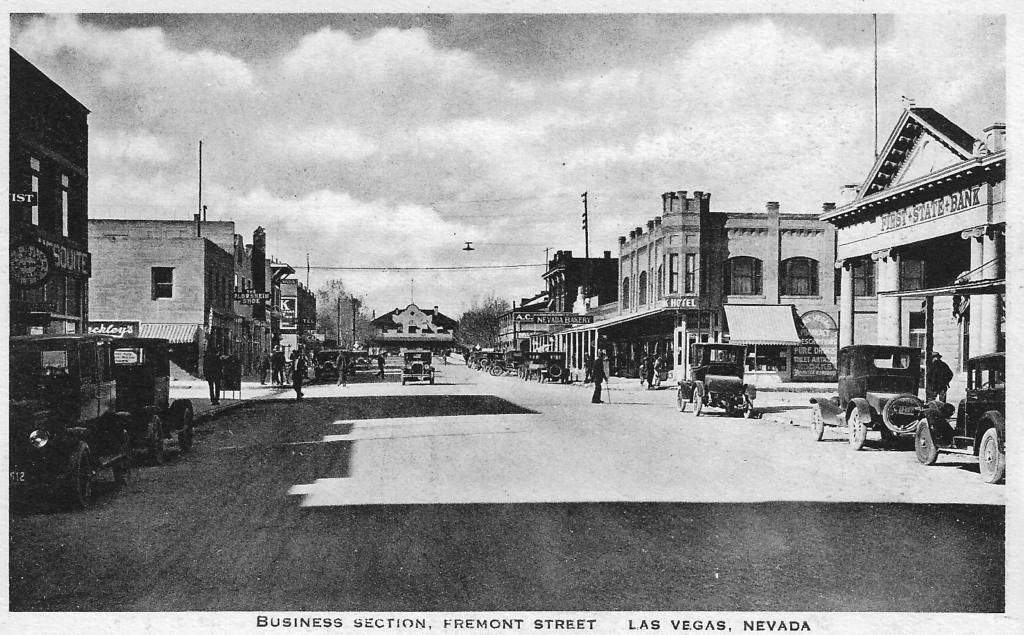

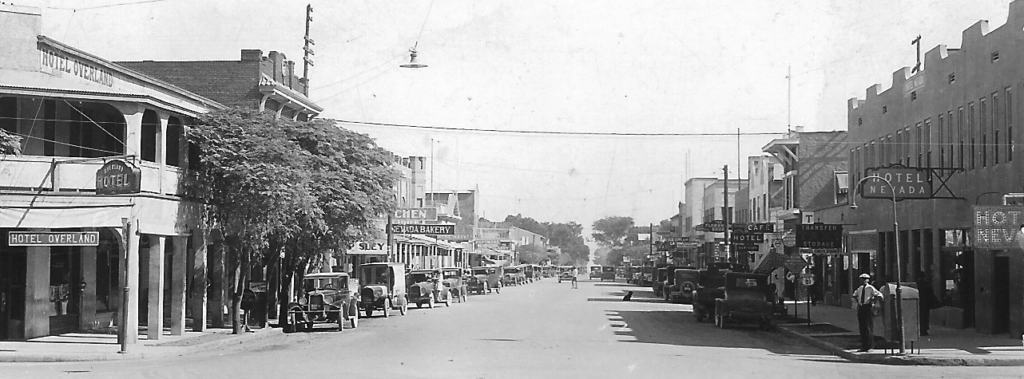

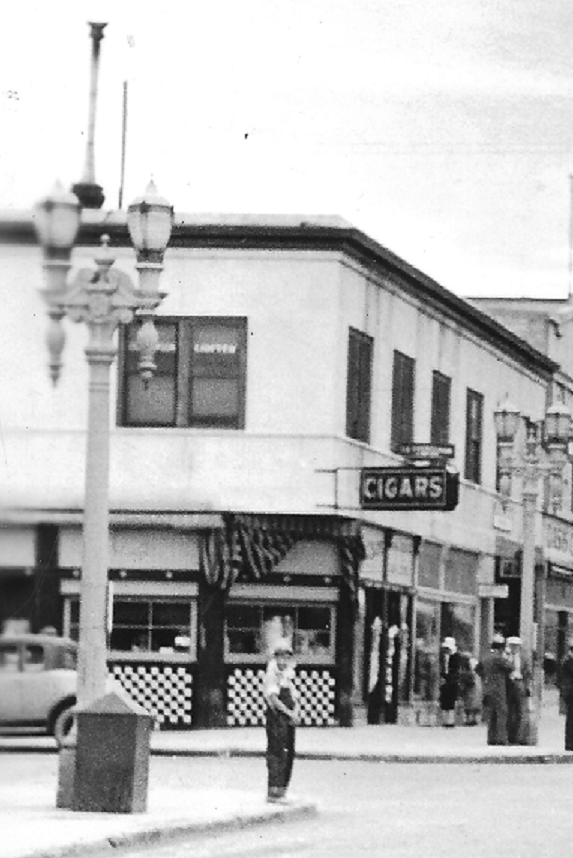

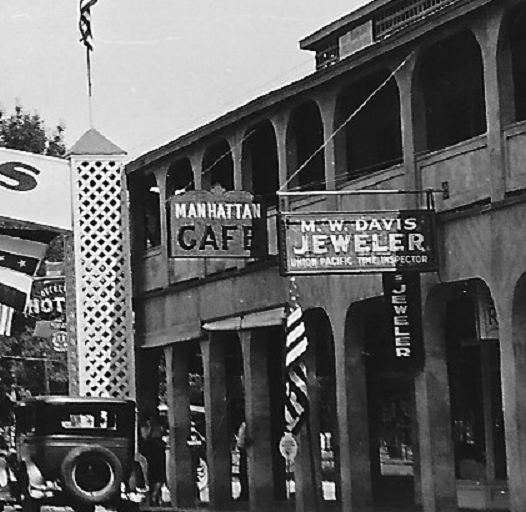

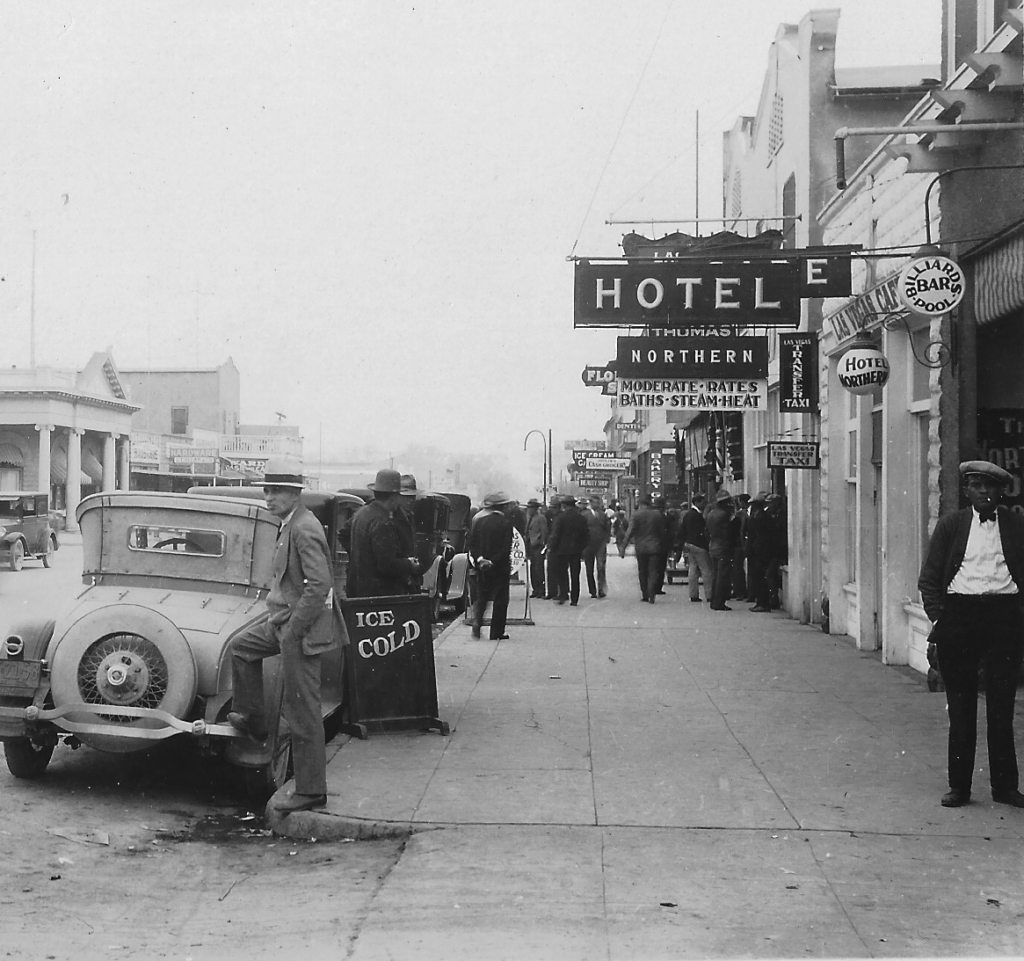

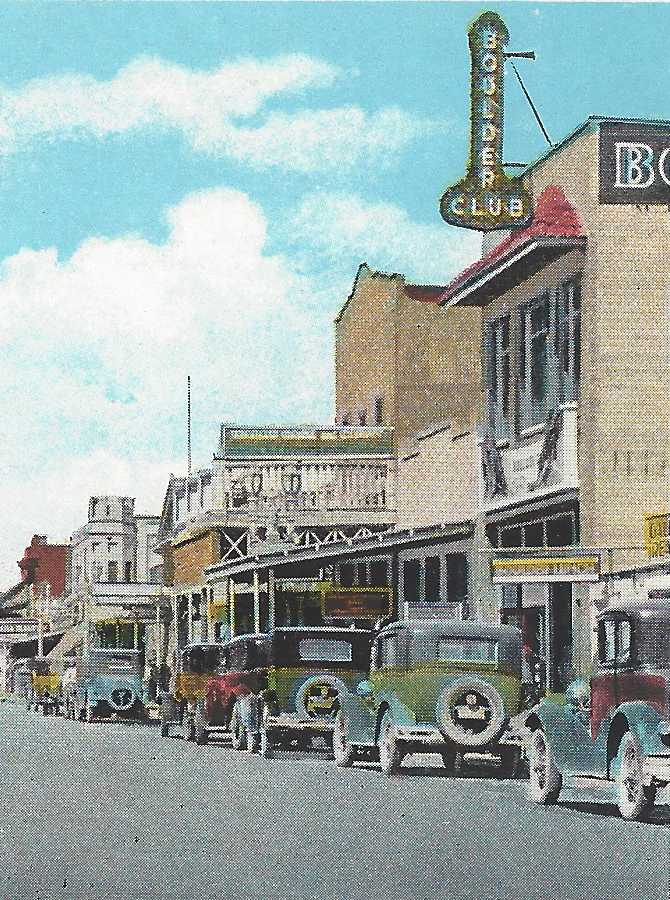

The heart of Las Vegas 1911 looking west from middle of 200 block of Fremont Street.

Mayme Stocker said she and her family arrived in Las Vegas either late in 1911 or as her youngest son Harold, believes, 1910.

Harold would later be elected to the Clark County Commission. His official biography on the county web site says “The Stocker family arrived in Las Vegas in October of 1911.”[ii]

Based on when the 1910 U.S. Census was taken, the Stocker family was in Los Angeles on April 16, that year. [iii]

In the census, Oscar is listed as a “switchman” on an unidentified railroad. Mayme, who listed her name on the census form as “Mamie V” did not list an occupation. [iv]

Her two oldest boys, 17 year old Lester Wellington Stocker, and 16 year old Clarence listed their occupation in 1910, as “messengers” for the “telegraph co.” [v]

Harold was listed as 8 years old and attending school. Born on March 8, 1900, rather than 8, Harold would have been ten years old at the time.

Mrs. Stocker was 35-years-old when she said she arrived in Las Vegas for the first time. She remembers it being May of 1911 and she was on her way to visit relatives in Butte, Montana.[vi]

She said, “I got off the train, along with a number of other passengers to see the town. The heat together with an array of drab buildings and thick dust under foot, was not conducive to a good first impression.” [vii]

In the 1948 interview, Mrs. Stocker remembered said she told one of the other passengers at the time “Anyone who lives here is out of his mind.” [viii]

But, then she said, “I didn’t know then that I would return to Las Vegas before the year was out to make my home.” [ix]

Her husband Oscar worked for the Union Pacific railroad in Los Angeles. Mrs. Stocker said her husband was transferred to Las Vegas late in 1911. She added, “A few weeks following his arrival here, my three sons and I came to Las Vegas to live.”[x]

Harold Stocker was eighty-year-olds at the time of the interview and he remembered his family arrived in 1910.

Whether it was 1910 or late in1911 is important for a couple of reasons. A labor dispute and school fire.

Las Vegas was the half way point between Los Angeles and Salt Lake City. The railroad line, the Salt Late Route, as it was called, was owned the Union Pacific Railroad, and former U.S. Senator from Montana, William Andrews Clark.

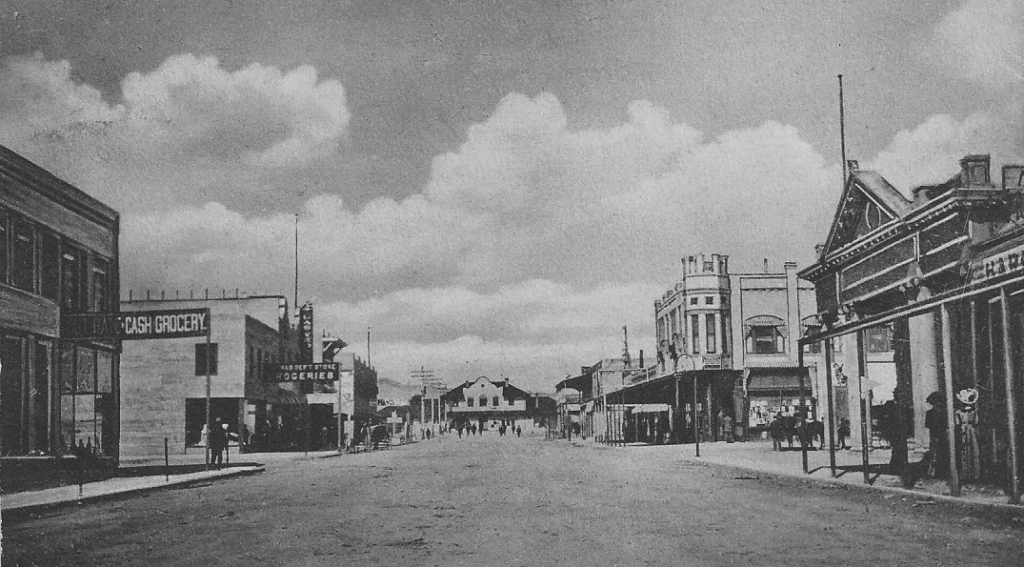

In 1911, the railroad had just finished building a massive large maintenance plant and complex for its trains in Las Vegas.

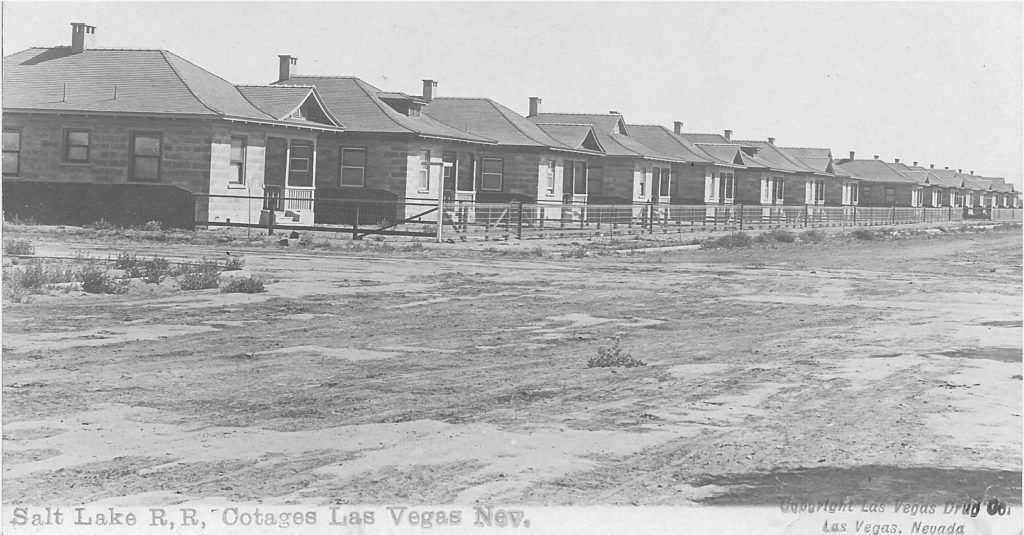

At the same time the railroad was building the maintenance complex, it was also building a large dormitory for the expected floor of workers. In addition, the railroad was also building more than sixty homes for men with families.

The homes, now known as the “Railroad Cottages,” were for the skilled craftsmen, like the senior Stocker.

Several of the cottages have been preserved. They were moved from downtown Las Vegas to the Las Vegas Springs Preserve and to the Clark County Museum.

Post card from 1911 of the Railroad Cottages on south Third Street.

If Stocker arrived in late 1911, he would have arrived in the middle of a labor dispute. A strike for recognition of the railroad shop workers started at the end of September, 1911.[xi]

Did Stocker, a strong union man, arrive in Las Vegas in the middle of the 1911 labor dispute, or did he arrive a year earlier in 1910?

If he arrived in 1911, it would be at a moment where the community and the railroad were at odds, but hopeful the dispute would be short.

In a move that upset the town, the railroad kept all the non-striking workers within the yards, building a fence around the entire maintenance complex, including the railroad commissary. The fences were topped with barb wire.

The men were housed and fed within the yards and were not allowed to go into town.

1911-1912. The railroad put up the fence around the shops to keep people both in and out. Author’s collection

“Las Vegas was still very crude” when she arrived in 1911 Mrs. Stocker said, “there were no streets or sidewalks, and there were no flowers, lawns or trees. One thing which impressed me was that all the homes were fenced. Even the court house had a fence around it.” [xii]

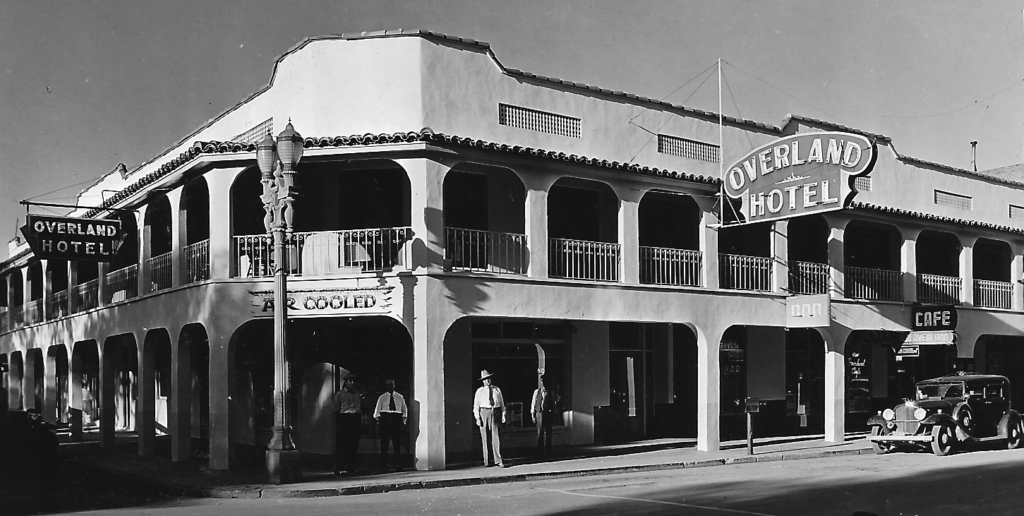

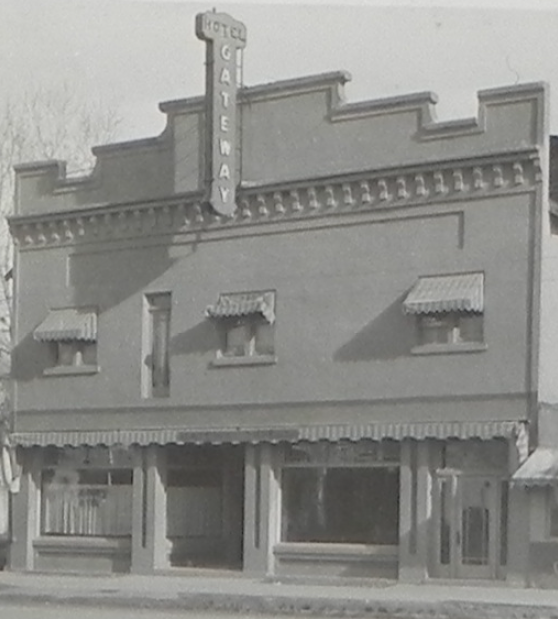

As far as housing she and her three sons, “We stayed at the Las Vegas Hotel, the second story of the building now occupied by the Las Vegas Club, until the late Harley A. Harmon, who was then county clerk found housing for us.”[xiii]

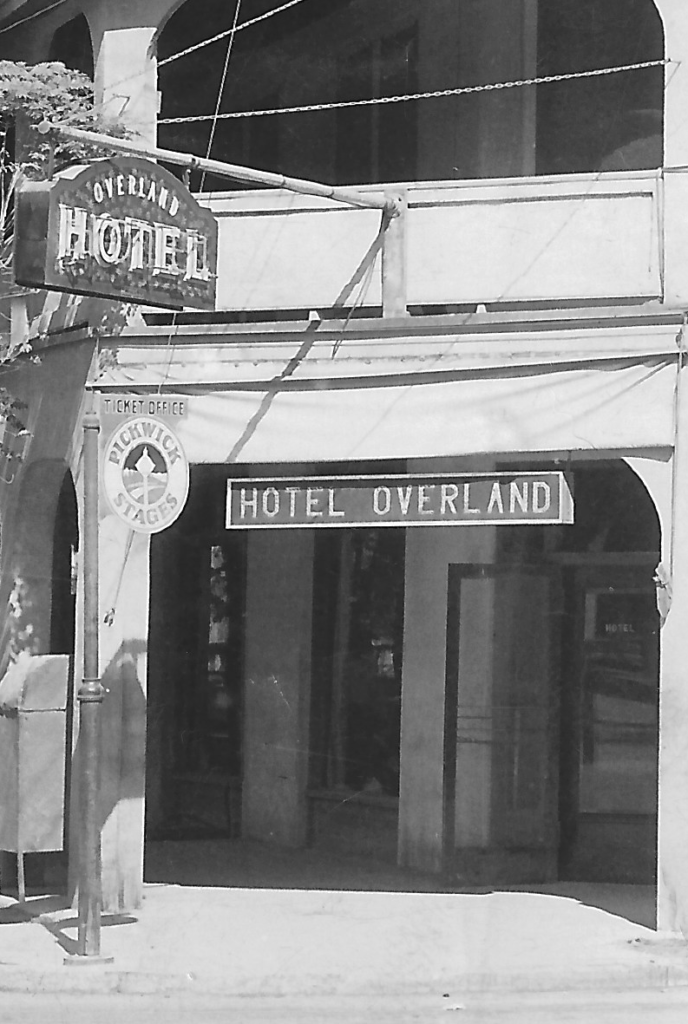

In 1911 the Las Vegas Hotel-Club, was on the south side of Fremont, just a door down from where the Northern would be built in 1912.

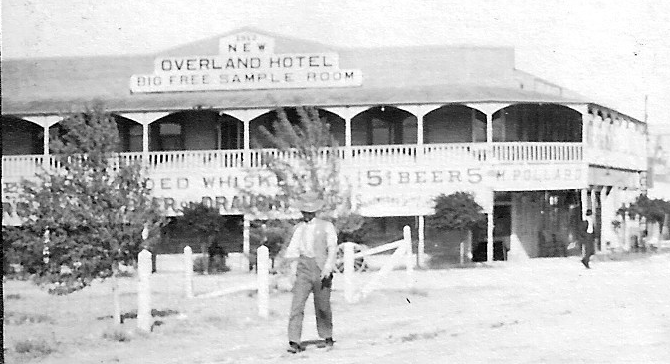

(The Las Vegas Club decades later would move to the north side of Fremont Street. I would occupy the Overland Hotel building, rebuilt in 1911, on the north east corner of Main and Fremont Streets. Both were torn down and became a large hole in the ground in early 2018.)

In Las Vegas the first public sign the strike was informally over occurred on April 27, 1912. The railroad announced effective May 1, it would no longer provide meals for their workers.

This was good news, according to the Las Vegas Age, “The commissary department at the shops will close,” and “the money which, since the beginning of the strike has been lost to the business of the city will again be thrown into the channels of trade greatly to the benefit of business in Vegas.” [xiv]

Newspaper publisher Charles Squires, who generally sided with the railroad in labor disputes, ended his story with, “We join with the entire city in a feeling of thorough satisfaction at this action.” [xv]

This all but ended the labor dispute in Las Vegas.

As the railroad hired replacement workers, the strike locally and nationally would soon fade, coming to a quiet end in a couple of years with the railroad recognizing the unions.

Another railroad strike would take place a decade later, and this time the Northern would play a major role. This labor dispute would find the governor of Nevada in Las Vegas with a gun in his hand.

While Squires may have had a “feeling of through satisfaction” for the “entire city,” 1912 was a time of stress for the Stocker family.

Starting at the end of 1912, and ending eight years, based on a variety of public sources and interviews with the Stockers, the family would spent most of their time in southern California: Los Angeles and San Pedro.

It is also likely during this period of time, in part due to the senior Stocker work with the railroad and his travel back and forth the family also maintained a home in Las Vegas.

The trigger to this temporary transition back to southern California was likely the arrest in Las Vegas of one of the Stocker boys.

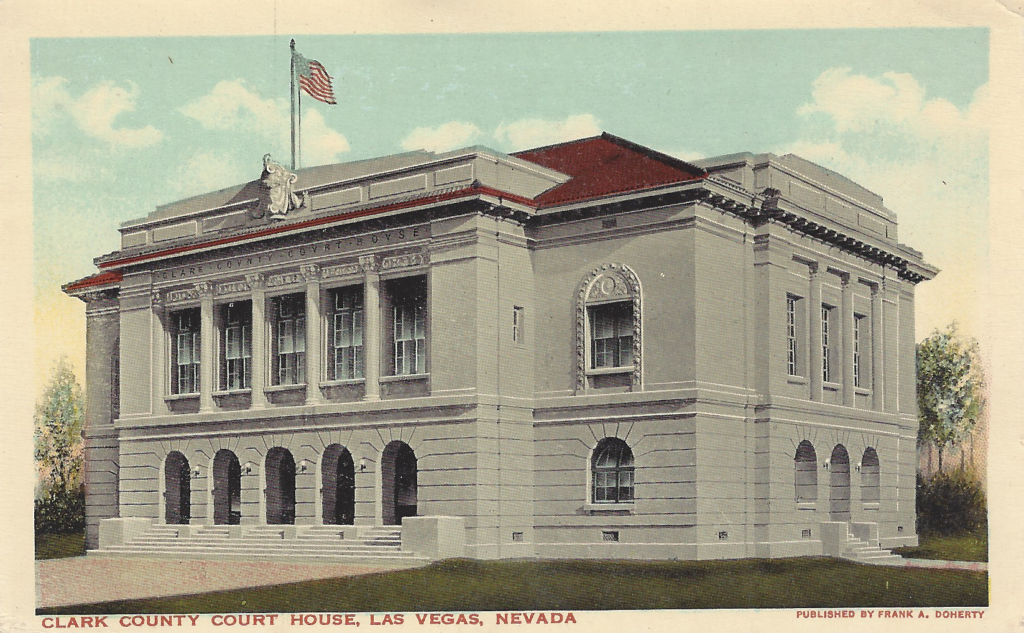

A command appearance at the brand new Clark County Court House came shortly after the Stocker’s oldest son Lester arrived in Las Vegas.

The nineteen year old Stocker was arrested in September of 1912.

The Las Vegas Age reported a cigar store had been burglarized and “suspicion at once fell upon two loafers who have been hanging around the place.” The ‘two loafer’ were identified as Patrick Murphy and a second person only identified as “a young blood named Stocker.” [xvi]

The two were taken to the city jail, “on a charge of burglary in the first degree.”[xvii]

On November 16, still being held on the burglary charge, the “young blood named Lester” celebrated his 20th birthday.

The following week the Clark County Grand Jury met, heard the case against the two men and only indicted Murphy.

All charges were dropped against Stocker, and he moved to Los Angeles.

Lester’s next run in with the law would turn out differently.

Based on voter registration records, and telephone directories it appears that Clarence spent most of his time from 1913 to 1919, in southern California.

Lester spent the early part of the decade with his brothers in southern California, but a visit to Montana in 1916 would require him to spent the next 3 years in that state.

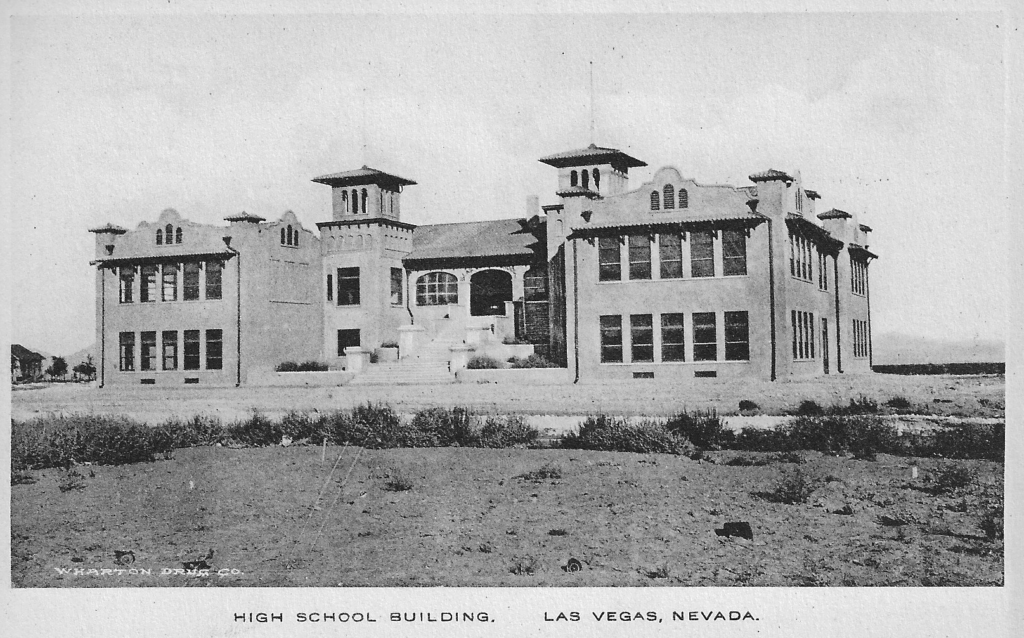

It is likely in 1913 Lester and Clarence were joined by Harold, and for a while their mother. Harold said the move to Los Angeles was due to a fire at Las Vegas’ grammar school.

As a new building to house both grammar and high school students was being built in October of 1910, a fire hit the existing school at Second Street and Lewis Avenue. [xviii]

Stocker says his mother had just arrived in town.

Harold would later say, the two of them left Las Vegas, “When the school burned down, I had to go to Los Angeles to go to school. We didn’t have a high school here.” [xix]

The new school building, at 4th and Bridger admitted students for the first time in October of 1911.[xx]

Harold, didn’t go to Los Angeles after the fire, as he was one of the students at the new Las Vegas school.

A 1911 post card. The new building was both a grammar and high school.

Harold was still in Las Vegas in the spring of 1912.

After his twelve birthday on March 8, he was put on the third grade Roll of Honor for being “neither absent nor tardy” and having “attained 80 percent cent in scholarship and department.”[xxi]

In 1913 Lester, and Clarence, along with their father were living at 1308 West 51st place in Los Angeles. Clarence listed his occupation as a telephone operator.

At the time, Lester was unemployed, and their father was a switchman for the railroad.[xxii]

For the traveling public the railroad was called the “Salt Lake Route,” officially it was the San Pedro, Los Angeles, and Salt Lake Railroad.

Likely the next move was related to their fathers work with the railroad, The three men moved in 1914 to 1409 ½ East 20th Street in San Pedro, California. [xxiii]

At the time, both Clarence and Lester listing said they were working as “clerks,” and their father, as a “brakeman.”[xxiv]

In 1916 Clarence registered to vote in Los Angeles, listing his address as 1021 Hillvale Avenue. In a different document, his brother Clarence is listed at five feet 4 inches tall, weight “approximately’ 130 pounds, with blue eyes.[xxv]

The next known public report shows Lester Stocker on his way to the Montana State Prison in August of 1916.

In the early summer of 1916 Lester was in Montana, he said he was only in the state “one week” before he got into trouble. He was said he didn’t have a job he and was just “doing nothing.”

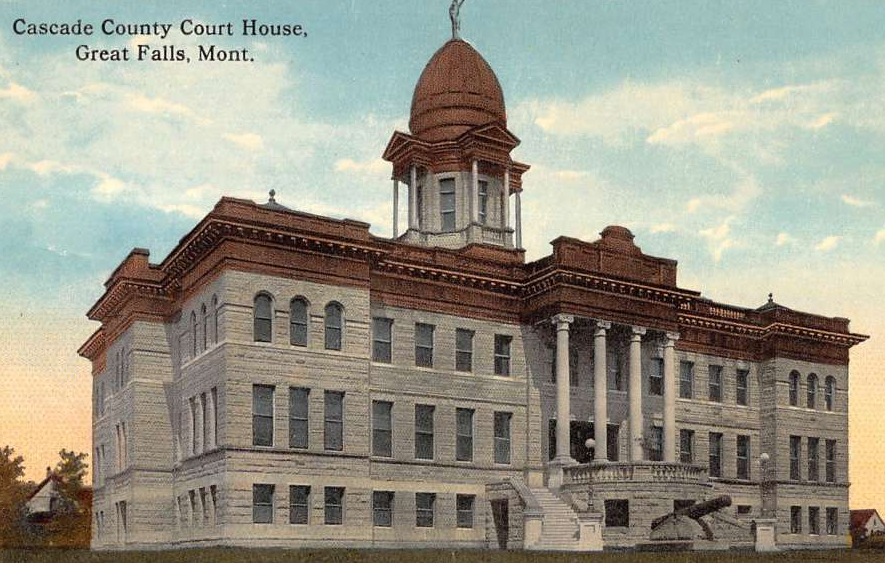

The “doing nothing”, according to the August 27, 1916 edition of the Great Falls Montana Daily Tribune, included the burglarizing of a jewelry store in Great Falls.

Stocker and an accomplice took “several pieces of valuable jewelry containing diamond settings.”

On August 31, 1916, in custody, Lester appeared before the judge at the County Court House in Great Falls, Montana.

When asked by the Judge how he pleaded to the charge of “Grand Larceny?’ Stocker said he didn’t have an attorney and pleaded guilty.

The judge sentenced him to serve to three and a half years in the Montana State Prison.

Lester told prison officials he was living with his brother at the Hillvale address in Los Angeles. [xxvi]

He also said “V. Stocker,” his mother and his father “O. Stocker,” were living in Los Angeles in the fall of 1916.

September 1, 1916 the day Stocker arrived at the state prison in Deer Lodge, Montana.

Author’s collection

The youthful looking 23-year-old Stocker wrote on his prison registration he was only 21 years old and under occupation, wrote “none.”

The following June, still in prison, he registered for the draft. [xxvii] The registration records show Lester was of “Medium” height, “Medium” build, blue eyes and light colored hair. To the right is Stocker after the barber provided him with a prison haircut.

After serving eighteen months, prison records show Stocker received his “Final Discharge” from the Montana State Prison on March 31,1919.

Within a few months of his release, the entire Stocker family would either be in Las Vegas or on their way.

Although Lester’s youngest brother would return to Las Vegas in 1920 an experienced gambler, it would be Lester who would become the first Stocker to get a gaming license in Nevada.

And sadly he would be the first one to die.

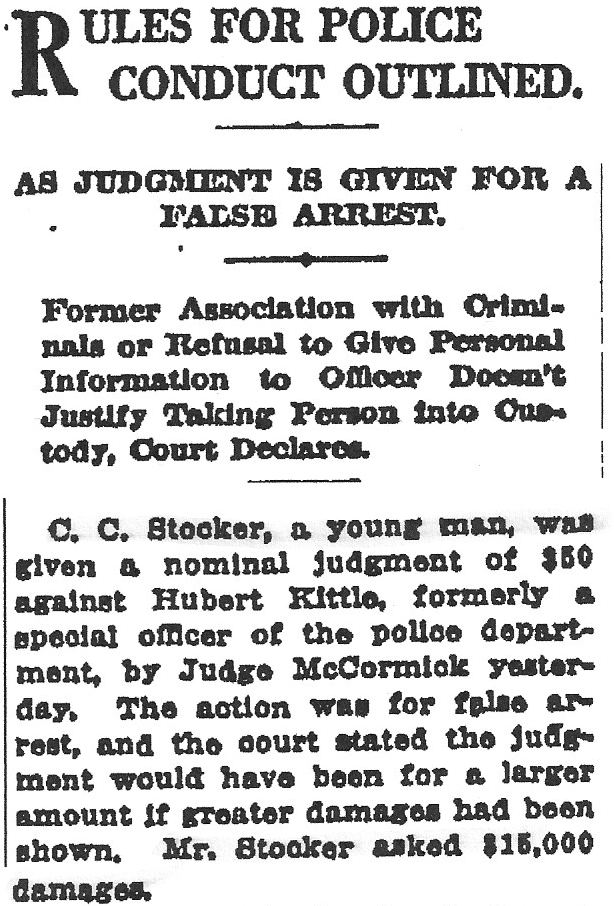

His brother Clarence also became familiar with the legal system. In the spring of 1917, Clarence was arrested at a “dance hall” in Los Angeles.

In court, “several witnesses testified that he ws under the influence of liquor and staggered, but Mr. Stocker said that was because he did not dance well.”

He was arrested by a “special officer” of the Los Angeles Police Department and “booked as a vagrant.”[xxviii]

The vagrancy charge was dropped, and Stocker took the officer to court asking for $15,000 in damages for false arrest. [xxix]

The former special officer, now working for the railroad as a fireman, claimed he knew Stocker. He said Stocker had “associated with criminals.” [xxx]

Los Angeles Times April 10, 1917

Los Angeles Times April 10, 1917

The judge ruled in Stocker’s favor say a person may not be arrested on “the ground the person formerly consorted with criminals.” [xxxi]

The judge only awarded Stocker $50 saying the “judgement would have been for a large amount if greater damages had been shown.” [xxxii]

The third and youngest brother, Harold, says after moving back to Los Angeles from Las Vegas. He attended school, and while in high school he became the family’s expert on gambling.

Over the years, Harold Stocker was interviewed by several journalists including A.D. Hopkins, as well as late UNLV History Professor Ralph Roske.

From those interviews the following is pieced together. Harold’s story didn’t change over the years, it just grew.[xxxiii]

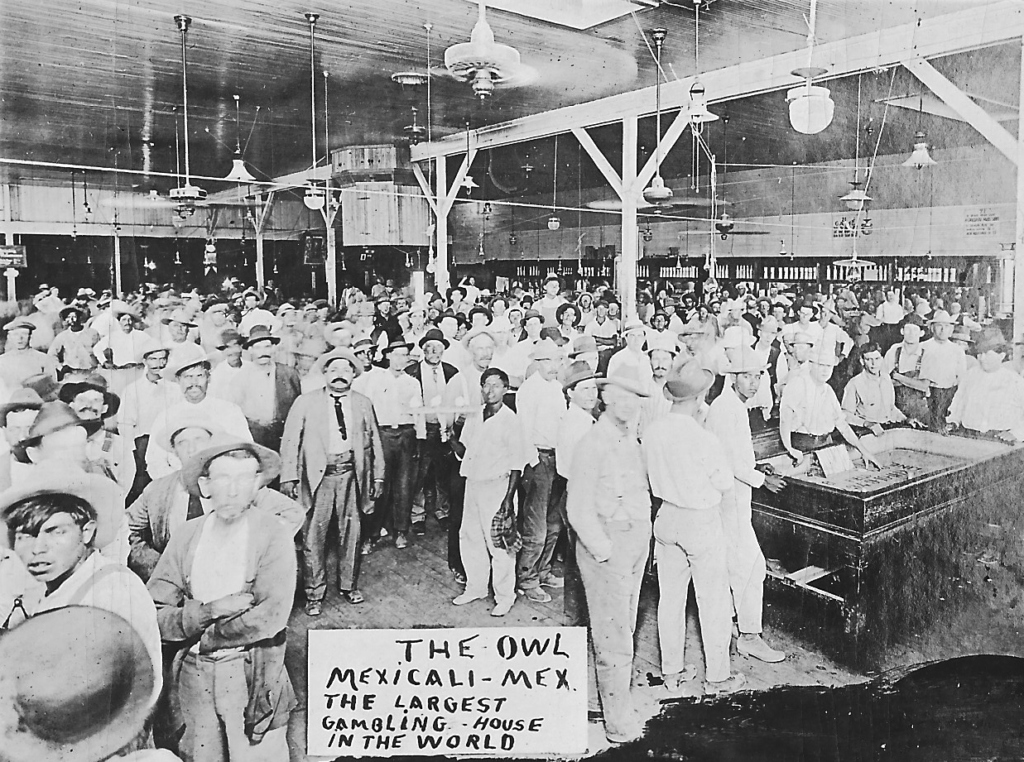

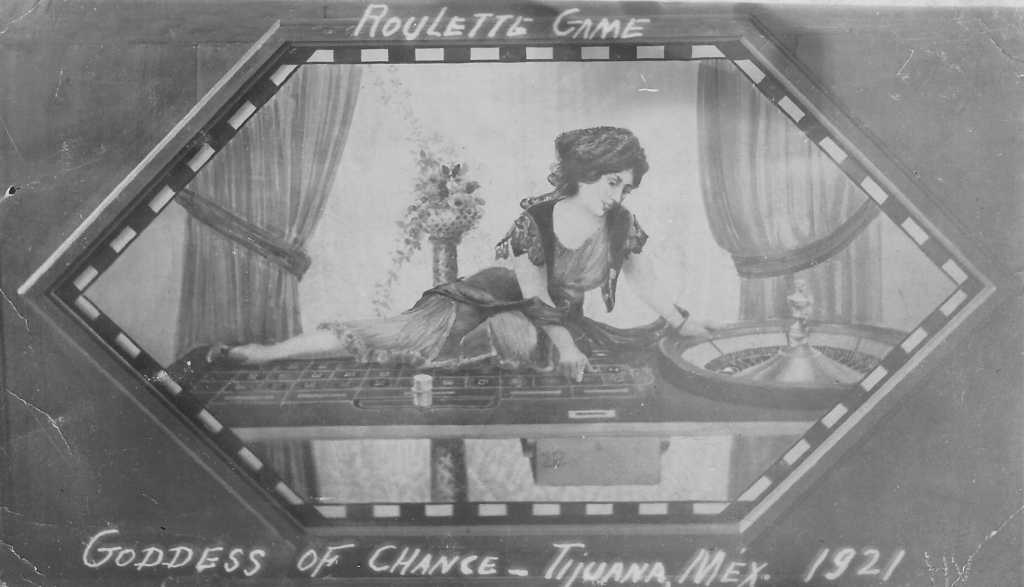

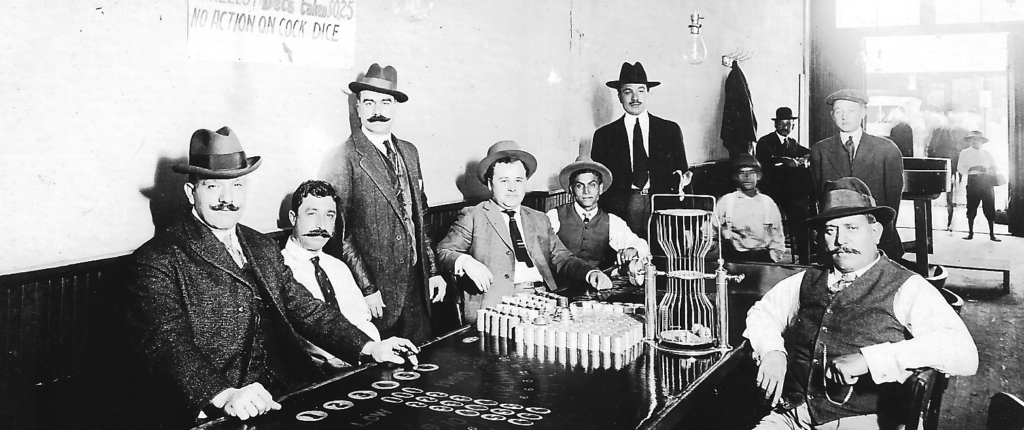

Harold said he started going to the U.S. Mexico border towns including Calexico and Tijuana starting in 1915; “I was fifteen-year-old, I used to work every summer. I was big husky, weighted 200 pounds you known, played freshman football. I was working in a studio in Los Angeles, when I was a kid, and (in audio, sounds like he says Tom Mix) this movie director (also later Harold says it was a “producer”) took a liking to me and would take me down to the border.”

Stocker says he met members of the A.B.W. Combination, which operated the Owl Club. Stocker said he knew a member of the ‘Combination,’ “Carl Withington, who used to be from up around Bakersfield.”

At first, the teenager Stocker said ,”I got a job racking chips at a roulette wheel. That was the game that had the most play in those days. That and 21 which we dealt with gold coins and big pesos.”

As far as a teenager working in Mexican casinos, Stocker said “It wasn’t illegal, there was no regulation there at all.”

“Being down there” Stocker said he “met a lot of people around the track and those kind of places you know and ah you naturally would pick up things. You are down there two or three months at a time, my mother was in Los Angeles.”

In addition to helping around the casinos, Stocker said they would “stake me at a card game at the hotel. Sometimes I win thousand, two thousand. For a 15 year old kid that’s a lot of money.”

It was now 1917, on April 16, the United States had formally joined the war in Europe.

Stocker recalled one tripe to Mexico, it was in the summer of 1917 his Hollywood friend “staked me to $500 to play in a “21” game while he went over and played Pan. “

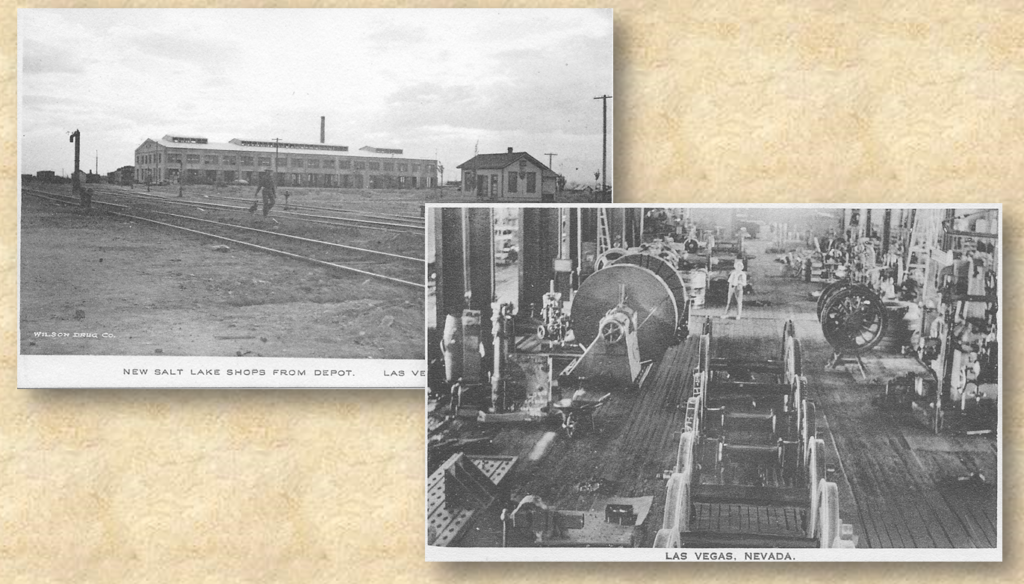

Images of Mexican clubs from Author’s collection.

Stocker said, playing blackjack, “I’d bet $5, which was the minimum until I had a hand, and then I’d bet $100. And if I lost, I’d go back to $5. When the summer was over my cut was $6,000. A lot of money for a 17 year old.”

When Stocker turned eighteen in March of 1918 he would soon begin his last summer working in Mexican casinos.

When he returned to school in the fall of 1918, he said he volunteered for the “Student Army Training Corp.”

Designed for university students to be trained as Army officers, Stocker said he was able to join in September of 1918.

Shortly afterwards he said his “unit was pulled out of school for active duty in costal defense at Fort MacArthur at San Pedro.”

Weeks later on November 11, 1918 World War One officially ended. Stocker would says years later he thought World War One was just “nonsense.”

“I was only in” the S.A. T.C. for a short time he said, “September to December of 1918. Then the flu bug came along and closed all the schools. I never did finish high school. Then I came back to Las Vegas in 1919 and went to work in the railroad shops as a machinist.”

Harold said he needed the job, “I needed to eat.”

It is clear that Oscar and Mayme were already in Las Vegas. Oscar was still working for the railroad.

With Lester either in prison or just getting out in 1919, where Clarence was is not known, but by the end of the year they were in Las Vegas selling cigars.

The U.S. Census, conducted at the end of January, 1920 shows the entire family in Las Vegas. [xxxiv]

Interesting, the federal census enumerator was James Germain who at the time also held the gaming license at the Northern.

Oscar listed his occupation as a “brakeman” with the railroad, which would be the Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad, also known as the “Salt Lake Route.” [xxxv]

When it came to Mayme “none” is listed under occupation. [xxxvi] Under the 1920 Census guidelines given to Germain rule 158 says, “in the case of a woman doing housework in her own home and having no other employment the entry should be none.”

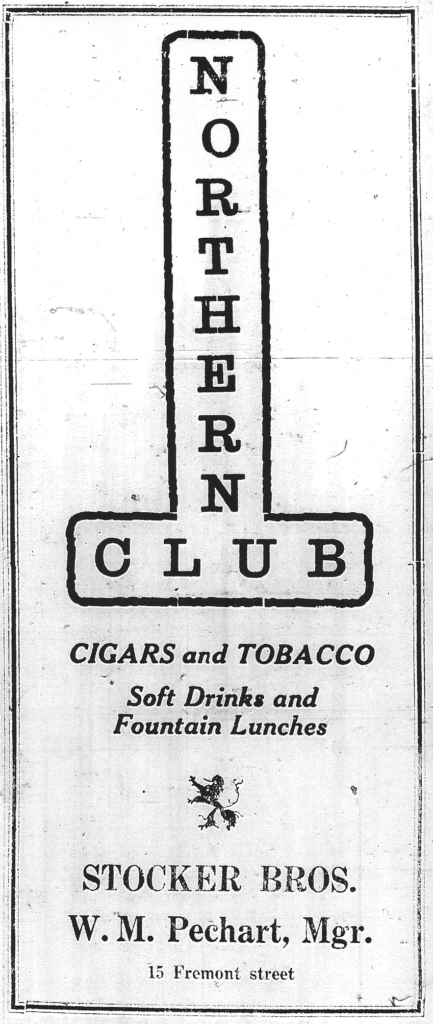

Both Clarence and Lester listed their “occupation” as “salesman” in a “cigar store.” [xxxvii]

Harold, like his father was employed at the rail yards. He was listed as a “Machinist Helper.” [xxxviii]

Within months of the census, the Stockers would begin first as proprietors , and then as owners of the Northern Hotel and Club.

Nearly three decades after the sale, Clarence would state it was the three brothers who originally bought the place in 1920.

This would be echoed by Harold who said they re-opened the hotel and named it the Northern on September 5, 1920.

Officially, the deed on file with the Clark County Recorder puts the year of purchase as 1921 and the father as the owner.

Another element of the sale stuck in Clarence’s mind for decades. Stocker was required to purchase of all the furniture in the building for $2,500. This brought the total cost to $14,500. [xxxix]

This is likely the furniture Groesbeck bought new eight years earlier.

Once the Stockers were able to examine in detail all the furniture, it was “in such a deplorable condition that most of it was hauled into the desert and dumped.”[xl]

At the time the Stockers took ownership of the Northern the social and economic order in Las Vegas began to dramatically shift.

And, the Mr. and Mrs. Stockers and their three sons were a major part of the “Roaring Twenty’s” in Las Vegas.

Coming up in part four, Part four The Northern becomes “A Strike Headquarters” for a massive nationwide railroad dispute and the oldest of of “My Three Sons” gets the families first gambling license.

[i] “Deeds,” Clark County, Nevada Recorder’s office, October 21, 1921, Book Eight, Page 565.

[ii] http://www.clarkcountynv.gov/parks/Documents/centennial/commissioners/commissioner-h-stocker.pdf

[iii] 1910, Census Place: Los Angeles Assembly District 71, Los Angeles, California; Roll T624_81; Page; 2B; Enumeration District 😉 143;FHL, microfilm: 1374094.

[iv] 1910, Census Place: Los Angeles Assembly District 71, Los Angeles, California; Roll T624_81; Page; 2B; Enumeration District 😉 143;FHL, microfilm: 1374094.

[v] 1910, Census Place: Los Angeles Assembly District 71, Los Angeles, California; Roll T624_81; Page; 2B; Enumeration District;) 143;FHL, microfilm: 1374094.

[vi] “Woman of the Week,” August 15, 1948, Las Vegas Review-Journal 7 Age, Section B, page 8.

[vii] “Woman of the Week,” August 15, 1948, Las Vegas Review-Journal 7 Age, Section B, page 8.

[viii] “Woman of the Week,” August 15, 1948, Las Vegas Review-Journal 7 Age, Section B, page 8.

[ix] “Woman of the Week,” August 15, 1948, Las Vegas Review-Journal 7 Age, Section B, page 8.

[x] “Woman of the Week,” August 15, 1948, Las Vegas Review-Journal 7 Age, Section B, page 8.

[xi] “Great Strike Is Now On,” September 30, 1911, Las Vegas Age, Page one.

[xii] “Woman of the Week,” August 15, 1948, Las Vegas Review-Journal & Age, Page 8B.

[xiii] “Woman of the Week,” August 15, 1948, Las Vegas Review-Journal & Age, Page 8B.

[xiv] “Commissary Closed,” April 27, 1912, Las Vegas Age, Page one.

[xv] “Commissary Closed,” April 27, 1912, Las Vegas Age, Page one.

[xvi] “Tap Hick’s Til,” September14, 1912, Las Vegas Age, page five.

[xvii] “Tap Hick’s Til,” September14, 1912, Las Vegas Age, page five.

[xviii] “Incendiary,” October 29, 1810, Las Vegas Age, page four.

[xix] “Stocker, Harold. Interview, 1971, November 30. OH-01773. Oral History Research Center, Special Collections and Archives, University Libraries, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Las Vegas, Nevada.”

[xx] “History of Clark County Schools,” by Harvey N. Dondero, compiled and edited by Billie F. Shank, 1986, Clark County School District, Las Vegas, Nevada, page 25.

[xxi] “Roll of Honor,” April 6, 1912, Las Vegas Age, page five.

[xxii] “Los Angeles City Directory, Stocker, 1913, Los Angeles, California, page 1814.

[xxiii] “Los Angles City Directory, Stocker, 1914, Los Angeles, California, page 2113.

[xxiv] “Los Angles City Directory, Stocker, 1914, Los Angeles, California, page 2113.

[xxv] World War Two registration card, April 26, 1942, Clarence Clifton Stocker, back of card.

[xxvi] “Registration Card, Lester Wellington Stocker,” June 5, 1917, World War One Registration form, number 4405, pages 1 and 2.

[xxvii] “Registration Card, Lester Wellington Stocker,” June 5, 1917, World War One Registration form, number 4405, pages 1 and 2.

[xxviii] “Rules for Police Conduct Outlined,” April 10, 1917, Los Angeles Times, Section II, page five.

[xxix] “Rules for Police Conduct Outlined,” April 10, 1917, Los Angeles Times, Section II, page five.

[xxx] “Rules for Police Conduct Outlined,” April 10, 1917, Los Angeles Times, Section II, page five.

[xxxi] “Rules for Police Conduct Outlined,” April 10, 1917, Los Angeles Times, Section II, page five.

[xxxii] “Rules for Police Conduct Outlined,” April 10, 1917, Los Angeles Times, Section II, page five.

[xxxiii] “Adventures in the bootleg business,” by A.D. Hopkins, January 4, 1918, Nevadan-Las Vegas Review-Journal page 26J, The following are from the “Stocker Family Papers, ID MS-00154 at UNLV Special collections and Archives; “The Day the Strip Was Born,” by Jim Seagraves, August, 1980, Clipping from magazine, UNLV Special Collection, Stocker Collection and Archives, “Stocker, Harold,” A. Kepper, March 13, 1918, two page set of notes, UNLV Special Collections and Archives. Stocker Collection. “Stocker, Harold. Interview, 1971 November 30. OH-01773. Oral History Research Center, Special Collections and Archives, University Libraries, University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

[xxxiv] 1920, United States Federal Census, Place, Las Vegas, Clark, Nevada, Roll: T625_1004; Page 23A; Enumeration District:3 .

[xxxv] 1920, United States Federal Census, Place, Las Vegas, Clark, Nevada, Roll: T625_1004; Page 23A; Enumeration District:3 .

[xxxvi] 1920, United States Federal Census, Place, Las Vegas, Clark, Nevada, Roll:T625_1004;Page 23A; Enumeration District:3 .

[xxxvii] 1920, United States Federal Census, Place, Las Vegas, Clark, Nevada, Roll:T625_1004;Page 23A; Enumeration District:3 .

[xxxviii] 1920, United States Federal Census, Place, Las Vegas, Clark, Nevada, Roll:T625_1004;Page 23A; Enumeration District:3 .

[xxxix] “Poker, Whist, Bridge Only Games Allowed in 1st Gambling Club,” My 16, 1948, Las Vegas Review-Journal & Age, page 4 B.

[xl] “Poker, Whist, Bridge Only Games Allowed in 1st Gambling Club,” My 16, 1948, Las Vegas Review-Journal & Age, page 4 B.

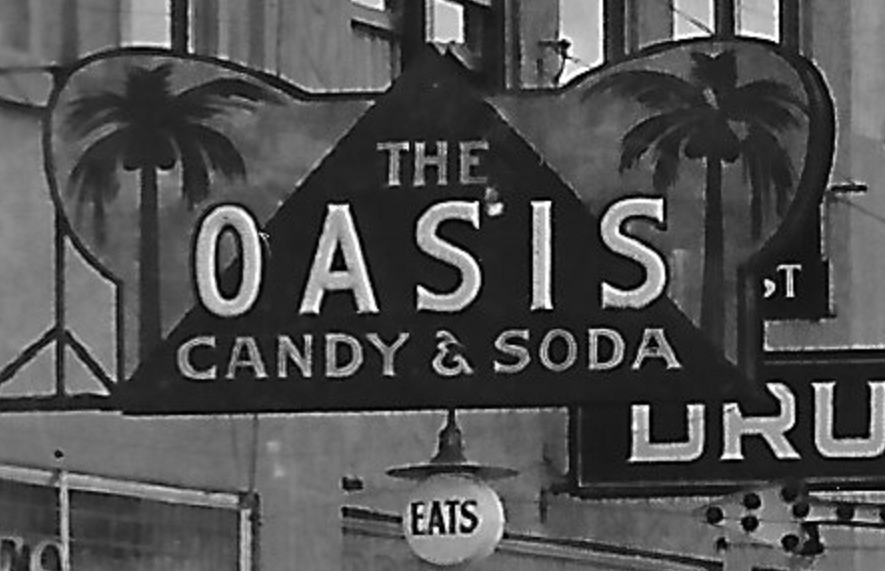

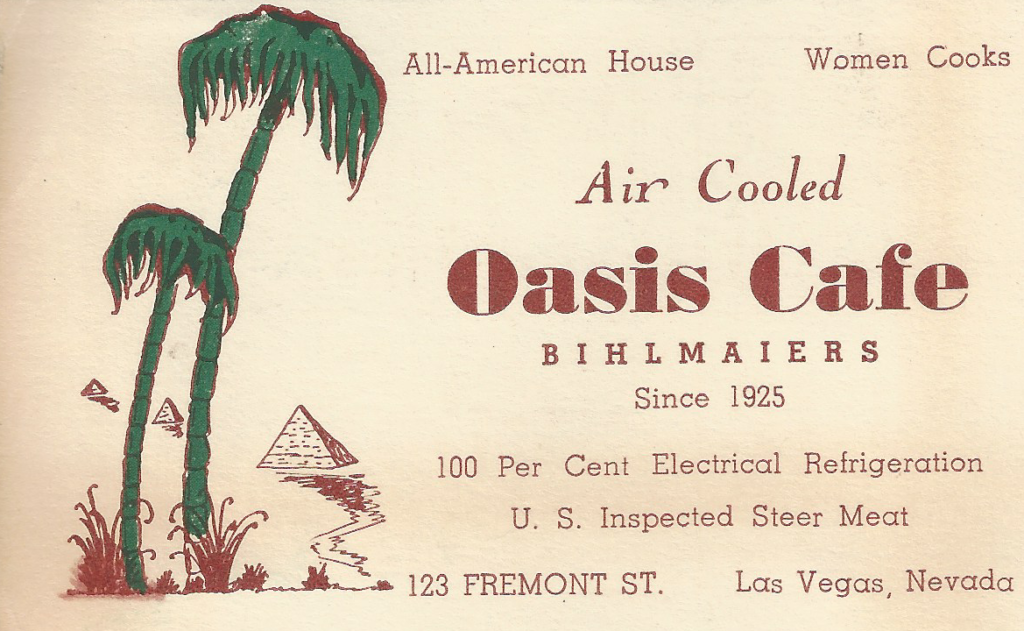

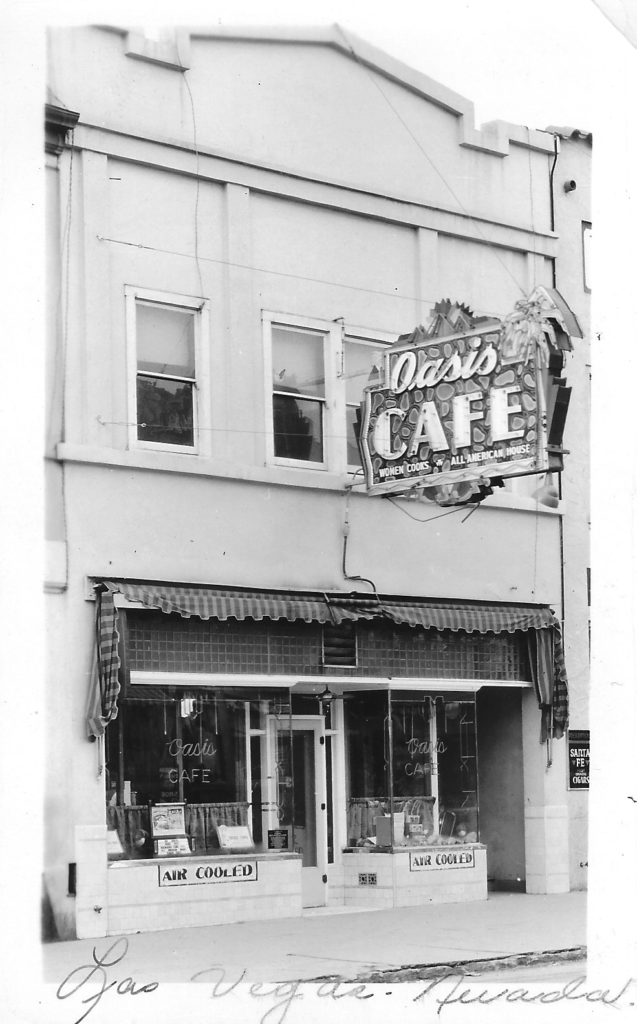

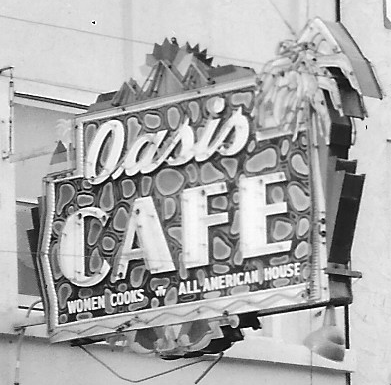

Oasis Cafe Business card.

Oasis Cafe Business card. Early 1930’s Post Card.

Early 1930’s Post Card.

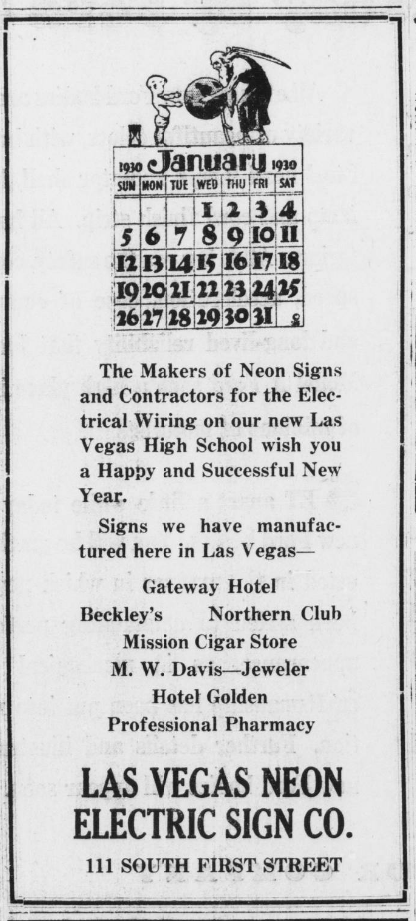

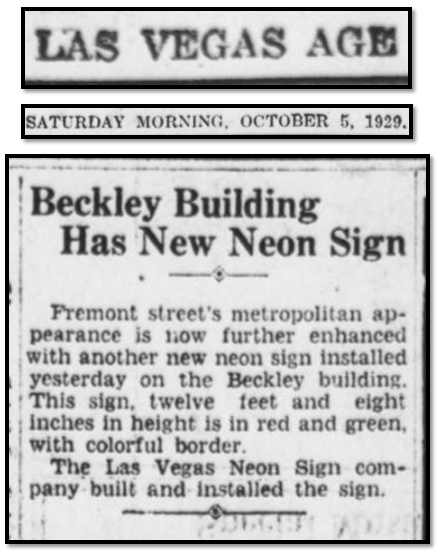

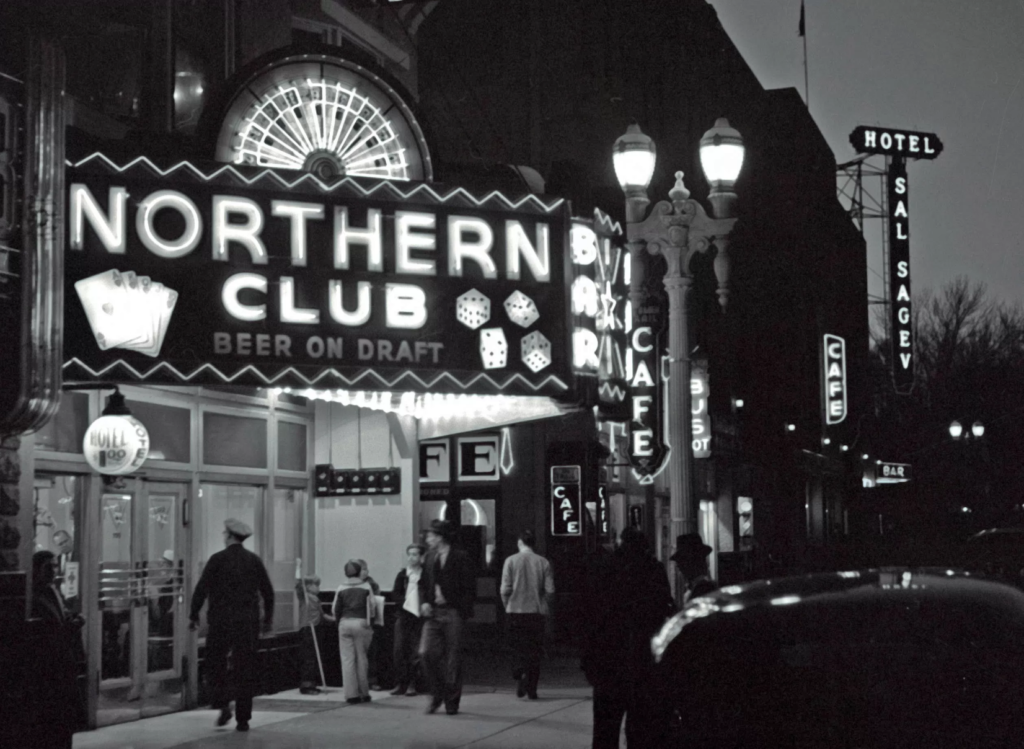

As the Bruce Brothers were assembling and installing the Boulder Club sign, Barrett’s Las Vegas Neon Electric Sign Company had secured a contract from the Northern Club.

As the Bruce Brothers were assembling and installing the Boulder Club sign, Barrett’s Las Vegas Neon Electric Sign Company had secured a contract from the Northern Club.

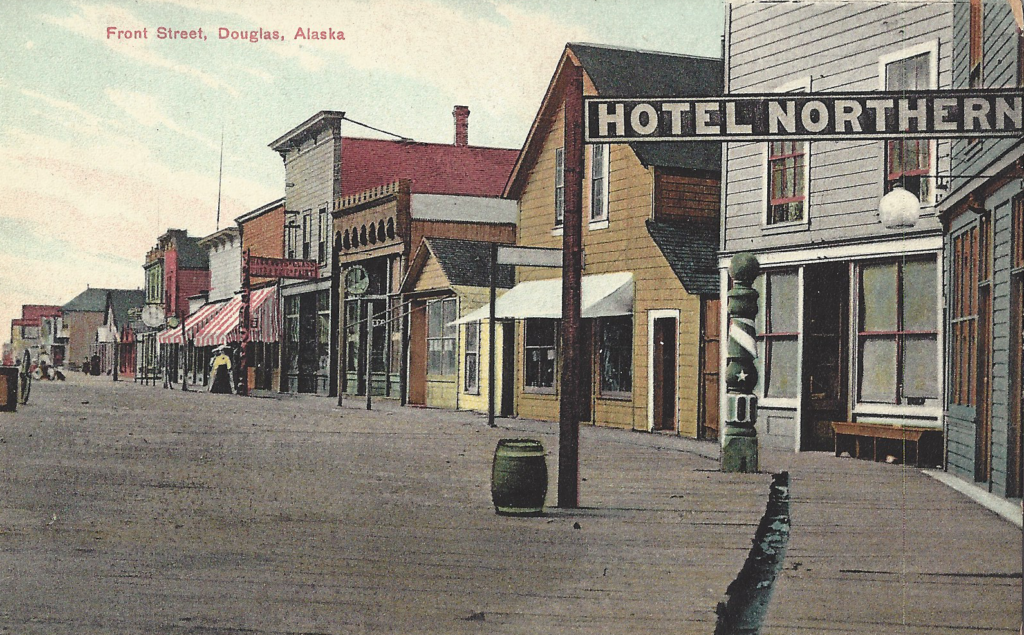

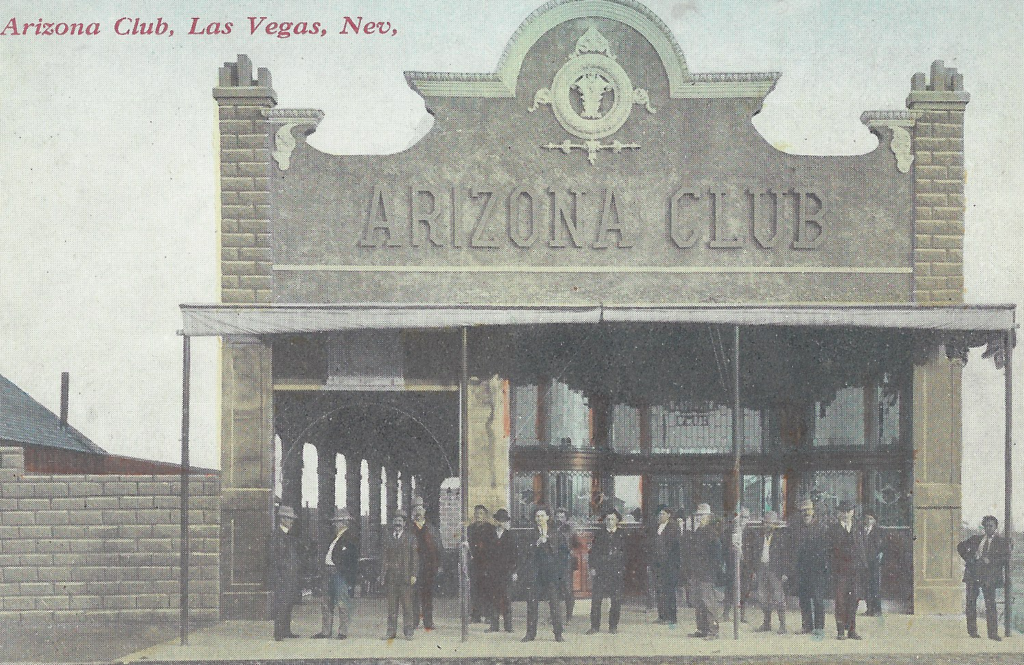

Whether it was a hotel, or a saloon, no self-respecting Nevada mining camp or community was without a “Northern.”

Whether it was a hotel, or a saloon, no self-respecting Nevada mining camp or community was without a “Northern.”

Author’s collection

Author’s collection

Author’s collection

Author’s collection

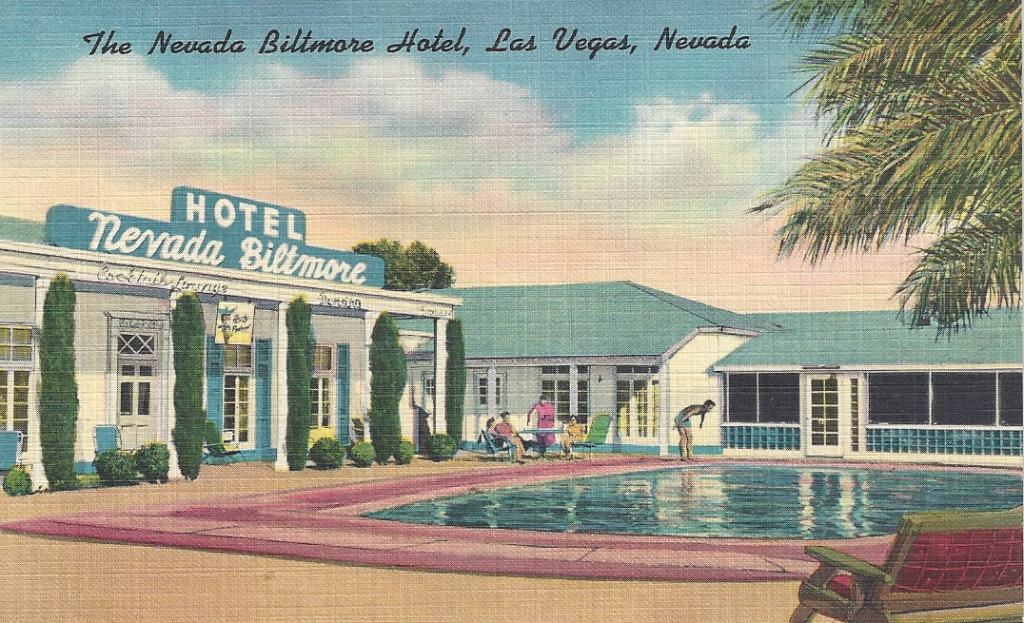

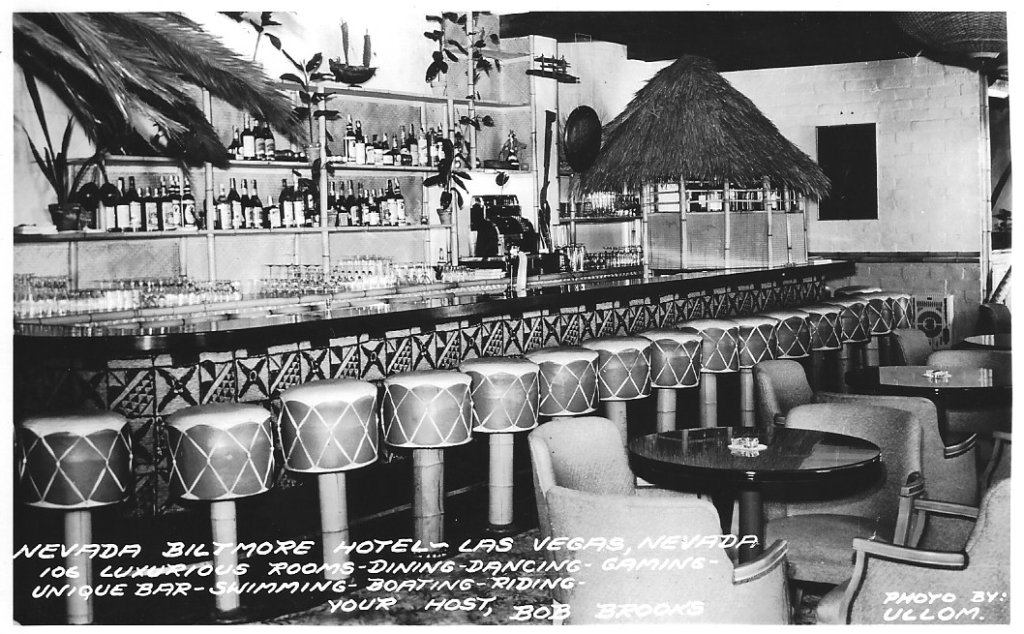

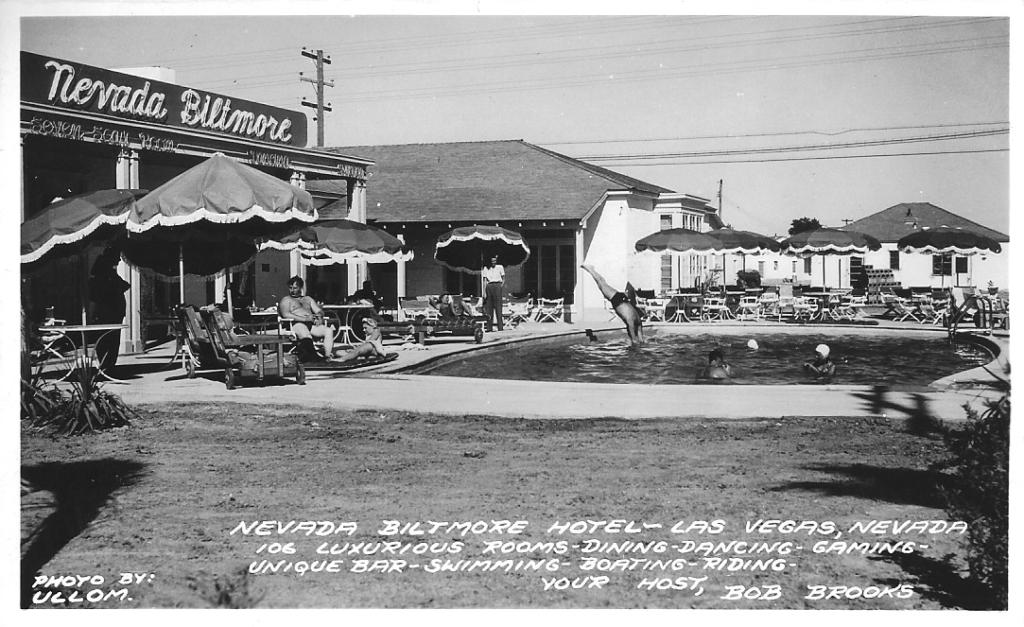

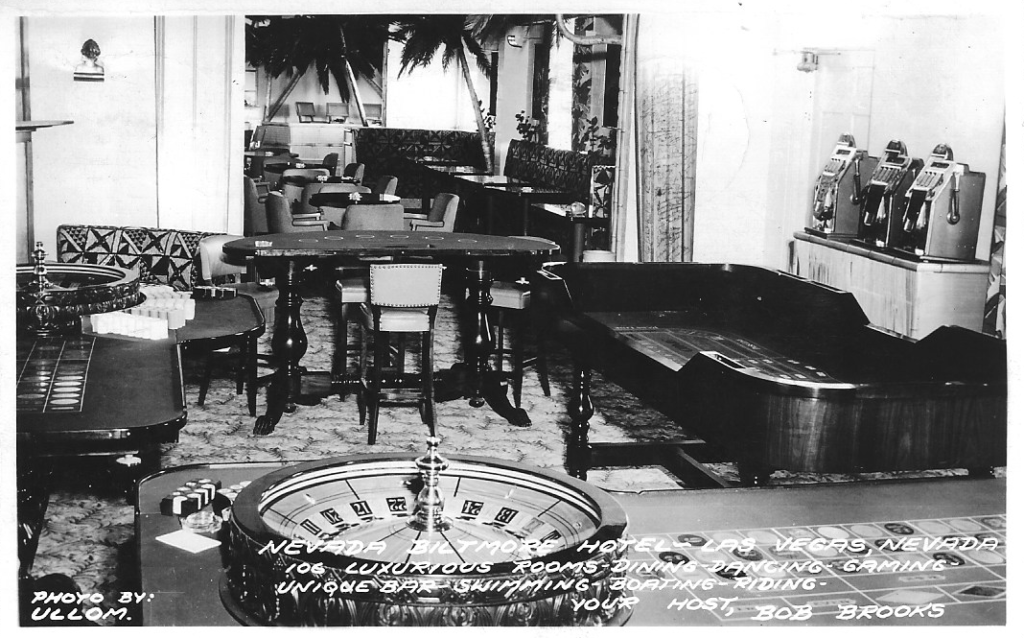

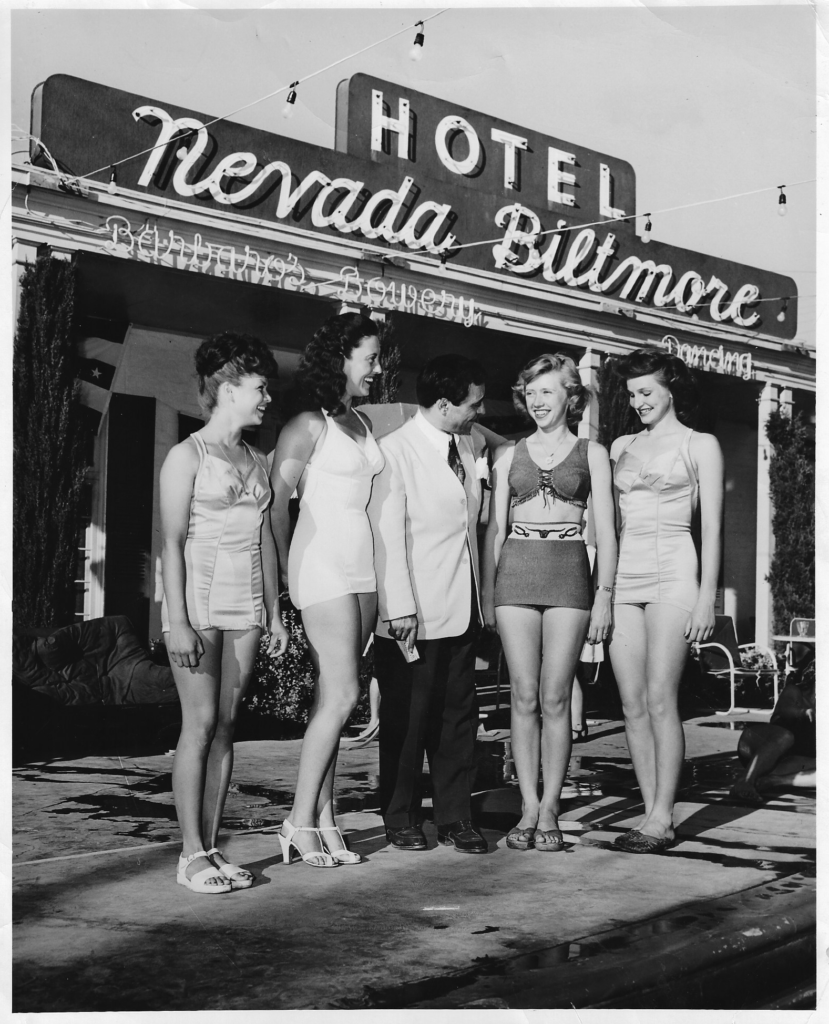

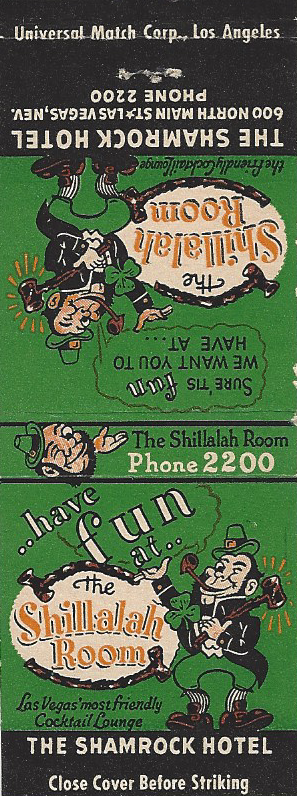

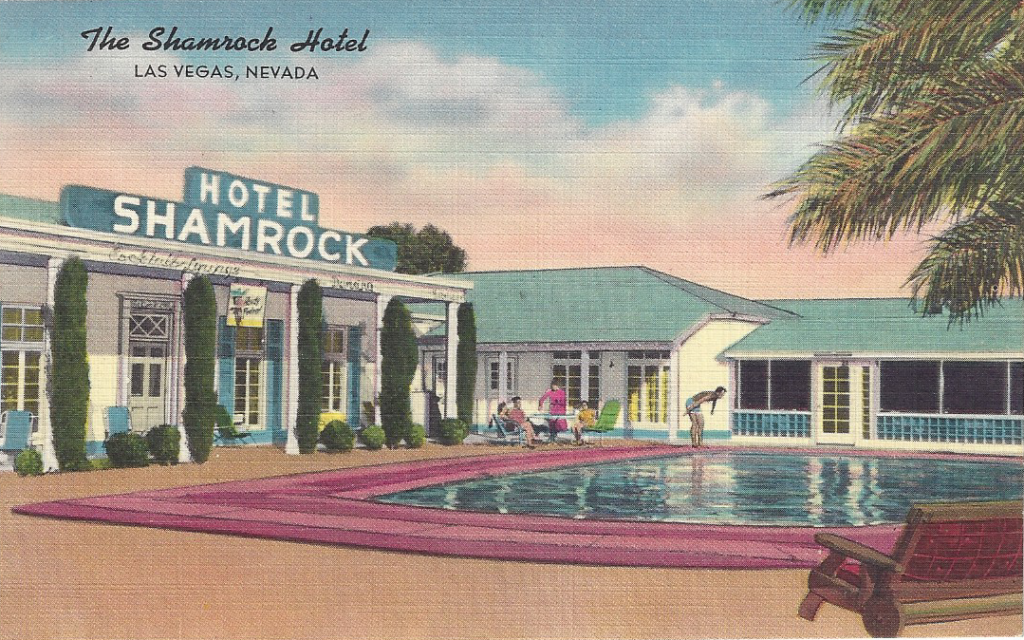

The pool was visible from the from the intersection Main and Bonanza Streets, which was also where two U.S. Highways, U.S. 91 and 95 connected. A popular place for locals. As a child, U.S. Senator Richard Bryan learned to swim in this pool.

The pool was visible from the from the intersection Main and Bonanza Streets, which was also where two U.S. Highways, U.S. 91 and 95 connected. A popular place for locals. As a child, U.S. Senator Richard Bryan learned to swim in this pool.

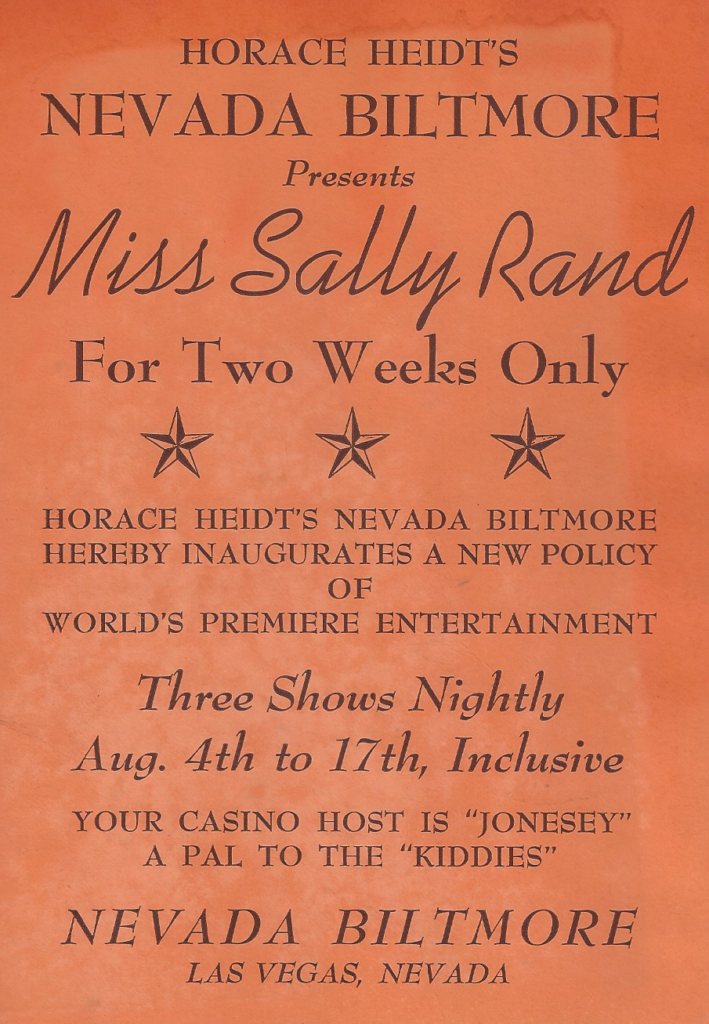

He billed himself as “known from coast to coast” and “your host from coast to coast.”

He billed himself as “known from coast to coast” and “your host from coast to coast.”

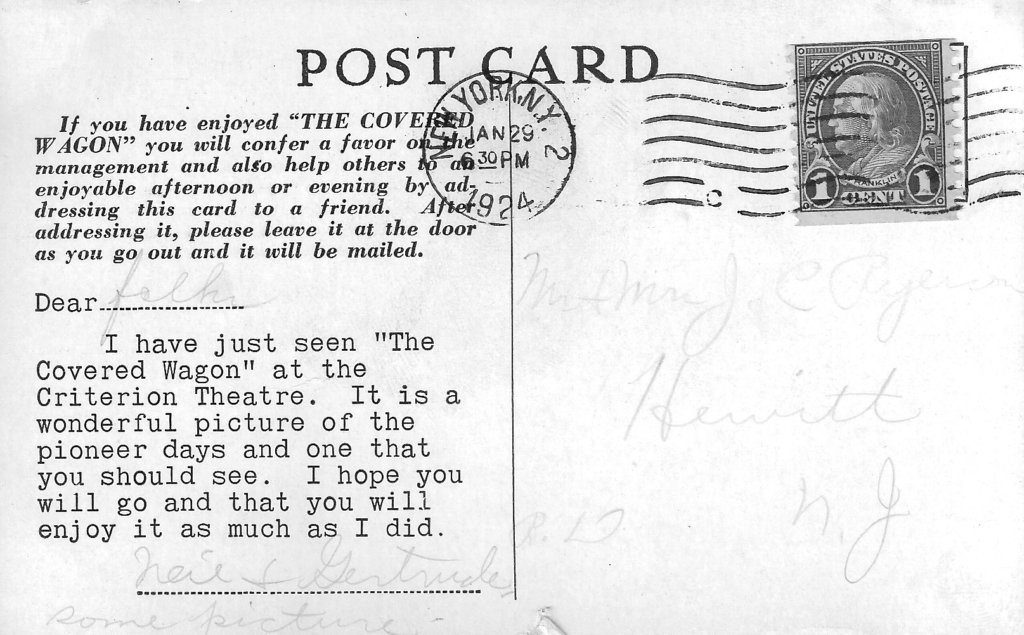

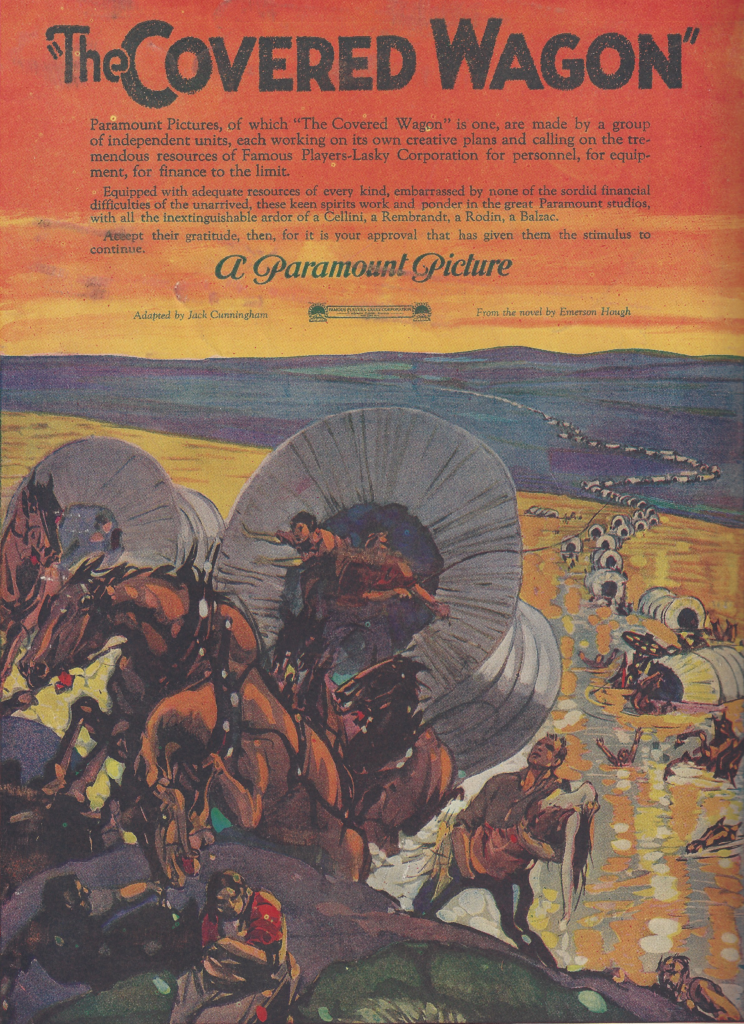

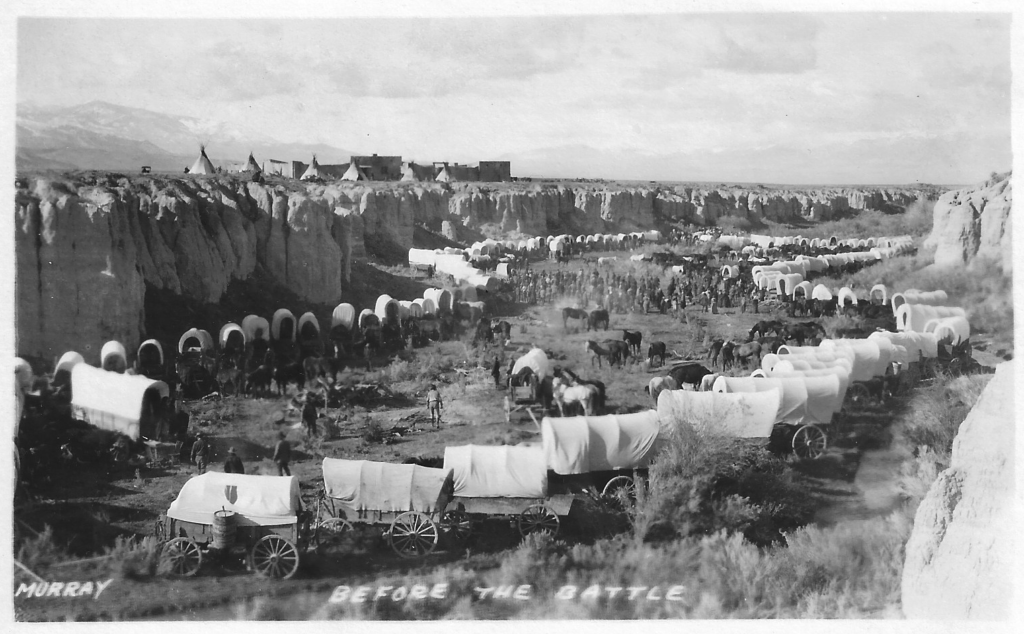

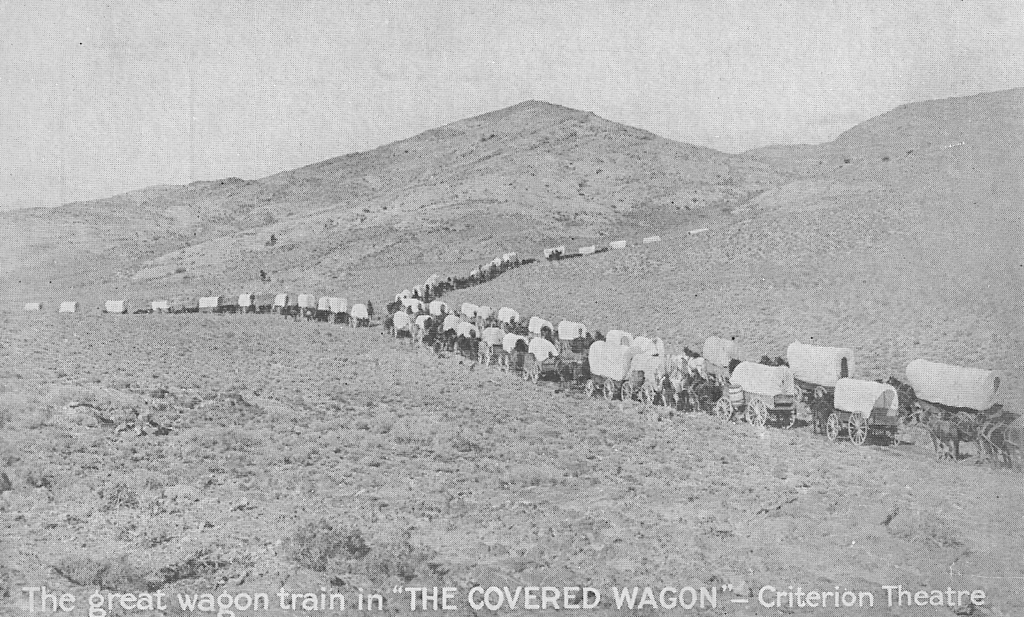

When the movie was released in the United States and England, theatre goers were asked to fill out post cards and send them to friends.

When the movie was released in the United States and England, theatre goers were asked to fill out post cards and send them to friends.