This is the first of a series of articles on motels of Nevada. As motels in Nevada’s major metropolitan areas are being paved over, the important role they played in the development of the state’s hospitality industry is also being lot.

While still alive and well in places like Boulder City, and communities along Interstate 80, and smaller tourist destinations in Nevada, the fight for survival is a daily battle.

The focus of this article is a short overview on the status of motels in Las Vegas.

You don’t it always see it go

and you don’t know what was on that spot until its gone,

They are thinking about paving the Par-O-Dice

and putting up a parking lot

after filling the pool with dirt and rock.

The Tumbleweed, Desert Rose and Royal Palms are gone. The Bagdad and Suez have also disappeared from the Strip, along with the Jamaica and Alaska. And most recently, the Blue Angel.

And the Par-O-Dice is still there, sorta!

The motels of Las Vegas are dying off, and the remains of the dearly departed are scattered around the valley, with linoleum-clad concrete slabs serving as tombstones.

It’s difficult to imagine that, for more than 70 years, motels were an essential part of the community’s tourism industry. By 1960 they packed the Strip and far beyond, from the “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas” sign to Fremont Street, and then east to Boulder Highway. At the height of golden era of motels, the late 1950s, there were nearly 40 on Las Vegas Boulevard south of Sahara, with more than 180 motels in the valley.

Now less than a dozen good specimens remain. Motel properties have been at the wrong end of the land-values balancing act for years. The glow of their neon signs, which once so warmly welcomed the motorized tourist to Fremont Street and the Strip, has been replaced by the massive multi-story digitized signs proclaiming of benefits of staying in billion-dollar resorts.

In other cases, such as Las Vegas Boulevard north of Sahara or east along Fremont Street, where you once found dusty for-sale signs in front of long-vacant motels, or just empty spaces where some of our classics once stood.

Today, along Fremont many of the names of the motels have been changed.

With the fate of our history at the mercy of market forces, we are left in a preservation predicament: Will Las Vegas motels soon be found only on old postcards, or will a new business model emerge that preserves the last of these historic structures?

The question has not been answered, but secret, (yes secret) discussions, (maybe not secret, but private discussions) started in late 2017 and may become a reality in 2018.

Motels represent an interesting period in Las Vegas history, when the individual and his privacy were top priorities. Unlike the larger resorts, with their frenetic bells and buzzers constantly beckoning, the motel guest got to choose his own pace.

The buildings were set up to facilitate these consumer preferences, starting with the fact that guests could discreetly check in at the manager’s office right off the road and then park directly in front of their rooms.

The architecture of Las Vegas’ surviving motels fits the quintessential motel types.

From the air they look like the letters L or U, or parallel I’s. Attached to the office would often be a two-story neon sign designed to catch the eye of the driver and show off the essence of the motel’s motif.

An aerial view of the Lucky Motel on Fremont Street.

From the Lucky, to St. Catherine’s to the Chief to El Mirador to the Hitchin’ Post, the traveler often had a choice between Spanish and cowboy/western.

More work needs to be done to determine how a Fremont Street motel was named after a Dominican tertiary, mystic, and one of the patron saints of Italy.

These motels also represented the first “family era” in Las Vegas. In the late 1940s, the Bonanza Lodge boasted “fully tiled bathrooms,” a heated pool and “grassed play yard.” This family-geared advertising was common among the Fremont Street motels, including the Purple Sage, along with “7 foot beds,” also boasted a play area.

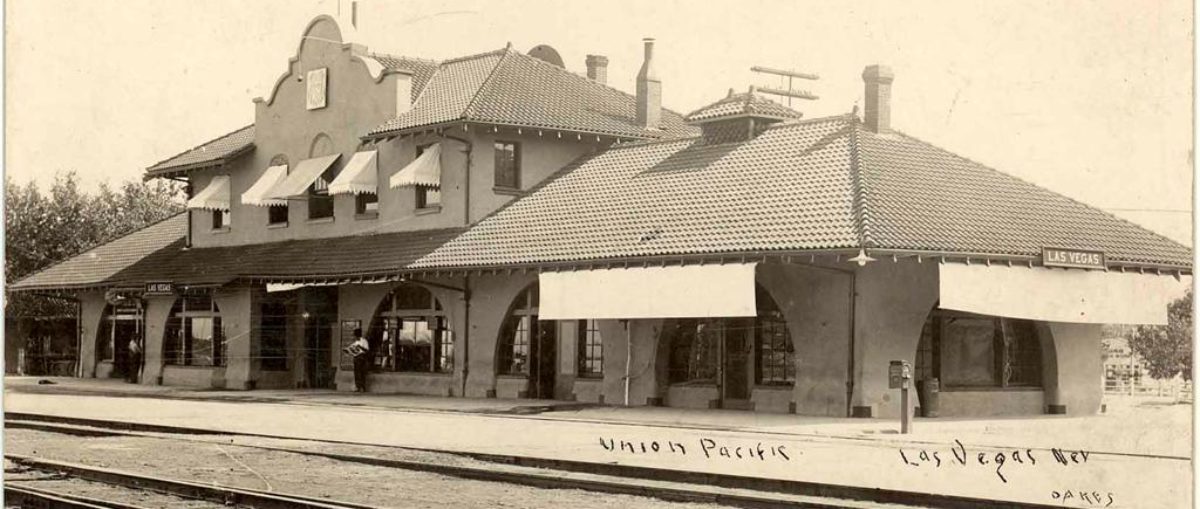

The history of “motor-hotels” in the United States can be traced back to the days before World War I. With automobiles beginning to be mass-produced during the 1910s, they became affordable for much of America, and with that change, travel was no longer limited to trains.

Auto Camps grounds, become turned into camp grounds for tents and cabins, which turned into only cabins, which quickly turned into a row of connected cabins with covered garages. Names sprouted up, Auto Camps, Auto Courts, Auto Inns, Autels, Motels, etc.

During this time, Las Vegans, working with their counterparts in Utah and Southern California, created a roadway between the two regions. They called it the Arrowhead Trail, through Las Vegas it was 5th Street, later to become Las Vegas Boulevard, and it also connected to the developing national highway system. The new motorized tourist needed services, including places to rest overnight.

In 1920s, architect Arthur Heineman came up with the idea of creating a series of small hotels to serve the automotive-traveling public along the California coast. At first he used the term “motor hotel,” then shortened it to “mo-tel,” and in 1925, he copyrighted the word “Motel.”

Meantime, in Las Vegas, motorized tourist looking for something other than a traditional hotel found it difficult to find accommodations that didn’t require camping equipment.

Then came J. Warren Woodard, who besides serving as Clark County sheriff, was Las Vegas’ first automobile dealer, selling Fords, Dodges and Hudsons.

In 1925 he got the idea to open the Down Town Camp, which offered more than just a flat spot of land; he promised his customers “clean cabins,” “shower baths,” a kitchen, a garage and free ice water. These were significant improvements for the traveler, but still a step away from motel-style accommodations, as the kitchen and shower baths that Woodard promised were communal.

No motels were listed in the 1931 Las Vegas Telephone Directory; the only automotive accommodations (all six of them) are listed under “Camp Grounds,” including Woodard’s. But as work began on Boulder Dam Project that year, and the state re-legalized gambling and made divorces easier, the motel industry took off.

By the mid-1930s, the Home Motel opened at 1401 Las Vegas Boulevard. Just like home, the new motel promised private showers and baths, and mattresses with “inner springs.”

A large market segment was drawn to this new comfort, as well as to the motel’s economy and privacy—two features most hotels didn’t have. Soon, dozens of motels prospered in the Las Vegas.

Most notable in the first wave was the Hotel El Rancho Vegas, which opened on April 3, 1941, with 63 rooms on the southwest corner of Las Vegas Boulevard and San Francisco Ave (Now Sahara Avenue.). The El Rancho had the primary architectural traits of a motel—it promoted “every room with a bath,” for example, and you could park in front of your room—but with the addition of a showroom and a casino, it was referred to itself as a hotel.

At the time the Clark County building code called for a maximum height of two stories for hotel and motel rooms on the Strip. That changed in 1955 when the county commission allowed for the construction of the nine-story Rivera Hotel.

The upward expansion of hotels proved to be the beginning of the end of Las Vegas Strip motels.

Today the future looks bleak for this part of Las Vegas history. The few remaining Strip motels and those along Las Vegas Boulevard and East Fremont Street will likely hang on until the next building boom, when these important artifacts will join the ghosts of tourism past.

One way to prevent this is to consider potential sites for the creation of a historic motel district. A similar strategy has saved portions of Route 66. That famous road, which once hosted a string of amenities from Chicago to Los Angeles, was removed from the federal highway system a quarter century ago. Since then, by popular demand, preservation efforts have brought the road brought back to life, along with many of its motels, gas stations and restaurants.

One potential area for a historic motel district is just north of Sahara between 2000 and 2400 blocks of Las Vegas Boulevard, where the motels have not yet turned into apartments with the rent due weekly.

Sitting in the shadow of the 1,100-foot-tall Stratosphere, on Las Vegas Boulevard between Oakey and Sahara Avenue several motels are holding the line on traditional motel business. This includes the Holiday House, at 2211 Las Vegas Boulevard, formerly the Bagdad Inn.

Opened in the mid 1950’s the owners of the Bagdad, then affiliated with Ramada, made an effort to expand the Las Vegas Strip into city limits.

Despite repeated efforts, even today, to promote the section of City of Las Vegas Between boulevard between Sahara and Oakey as being “On the Strip,” (not a chance) the “Strip” ends at the county line.

These excellent, largely preserved examples of traditional motels are at risk of succumbing to another high-rise project.

Another active motel district is north of the intersection of Main Street and Las Vegas Boulevard. However, its current activities are of the XXX variety. With the Cactus and Oasis motels offering fantasy room and free adult movie channels at one end, the Olympic Garden strip joint in the middle, and the Talk of the Town adult bookstore at the other end, restoring this motel corridor would be a long-shot.

Perhaps the best preservation opportunity lies on East Fremont, which has a collection of motels from the 1940s and ’50s that are not far from their original forms. You might even say that this stretch—once part of the U.S. Route 66 system—still has some of that old motel magic.

These buildings have had challenges, from the battle with the billion-dollar resorts to the closing of Fremont to eastward bound traffic. And, in some cases, time has piled on layers that would be difficult to remove. For example, the Las Vegas Motel, which once promoted itself as “a place for conservative travelers,” is now the Alicia. And because one owner bought out a neighbor, the old Fremont Motel is now the Alicia, too. In fact, the entire block of motels on the north side of the street, between Maryland Parkway and 13th Street, is the “fully remodeled” Alicia.

In the 2000 block of Fremont, just before Charleston, there is an interesting cluster of motels, including the Safari, Sky Ranch, Roulette, and Town and Country. While their heated pools are now filled to the brim with dirt and rocks, a few almost intact neon signs stand out as motels from the golden era.

At the end of this motel district, stood a beacon for all to see, is the symbol of survival, the blond-haired-Blue Angel.

Built in 1957, the Blue Angel motel was the center of a complex of business that supported both visitors and locals that included a fine restaurant the Blue Onion that included a drive-in section, with car service that became a key portion of the popular teenage cruise in the 1960s. (Tangent- There were two popular cruise routes. One- up and down Fremont Street, circling through the Union Pacific Depot, back east to the Blue Onion and back west. The second included a triangular route. Starting at the Blue Onion, west on Fremont, through the railroad depot, back east on Fremont to Las Vegas Boulevard. Turn south and at Charleston, southwest corner was the Tip Top Drive in. From there, multi choices. A. head east on Charleston back to the Blue Onion, b. keeping going south on 5th street to the Round Up Drive in, where 5th intersects with Main, or head back to Fremont Street. Back to motels.)

Today, the Blue Angel motel, and the Blue Onion restaurant are gone. But, through the efforts of Las Vegas City Councilman Bob Coffin, the Blue Angel herself will be restored and placed near the center of the intersection of Fremont, Charleston, Eastern and the start of the Boulder Highway. That is expected to take place before the summer of 2018.

Las Vegas Valley Motel Preservation

In addition to the secret/private work afoot on Fremont Street, one form of motel preservation is already under way: The Clark County Museum in Henderson created a small exhibit called “Mobile America,” which includes a travel trailer, and Cabin 14 from an unknown Las Vegas motor court. Found in a local back yard, the single cabin has been restored to show how it looked in the 1930s and ’40s.

The nonprofit Neon Museum organization, along with saving signs from long gone motels, is also preserving another important piece of our motel history: the La Concha lobby, designed by the famous Los Angeles architect Paul Revere Williams in the 1950s. It was saved at a cost of several hundred thousand dollars and moved to the site of the future Neon Museum (see Page xx), where it will be repurposed as a visitor center.

And there is more good news, potentially at least. Las Vegas Boulevard, from the welcome sign to Washington Avenue downtown, has been declared an “All-American Road” by U.S. Department of Transportation, as part of its National Scenic Byways Program. Congress established the program in 1991 to preserve and protect the nation’s scenic roads in order to promote tourism and economic development. Las Vegas Boulevard was awarded this designation due in part to the historic motels along it, and with the honor comes the ability to seek federal grants “for planning as well as enhancing and promoting” the roadway.

And there is one other place Las Vegas motels and its history are being preserved, the homes of collectors. From post cards, to stationary, to matches and ashtrays, and yes, those small rectangular pieces of soap, bits and pieces of Las Vegas motels, are being preserved.

More on collectors and the history of specific Las Vegas motels and any update on the secret/private plans for Fremont Street in future blogs.